The Trail of Death

There is so much that can be said about this topic. The fact is, that it has been documented in many publications, and – as a trail – covered with markers and monuments.

If you would like to read about it in its entirety, please contact the Fulton County Historical Society and purchase their book on this topic, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell.

Included here is a synopsis, almost straight from Wikipedia, which actually has the facts almost straight. (They had the name of the river wrong.)

The synopsis is followed by short stories written by descendants.

Synopsis

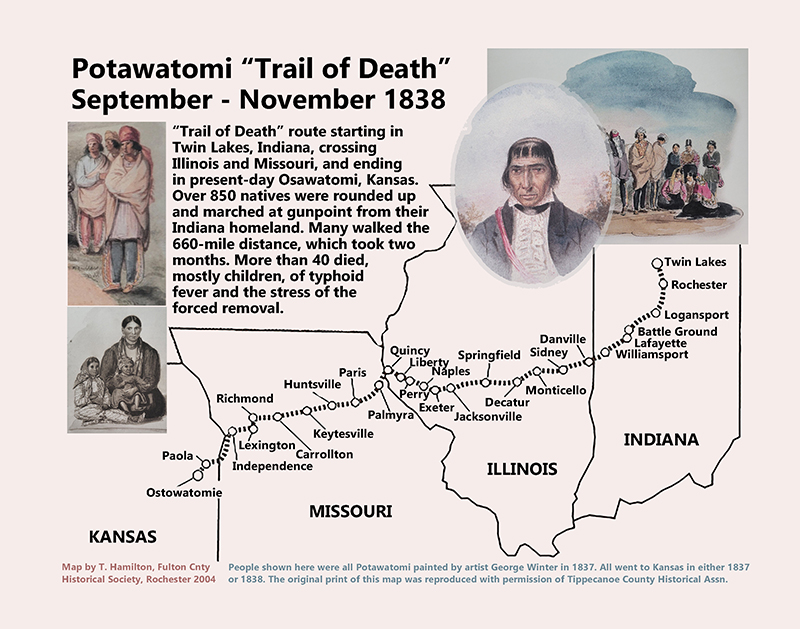

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of some 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas. The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook Lake, near Plymouth, Indiana) on November 4, 1838, ending near present-day Osawatomie, Kansas. During the journey of approximately 660 miles over 61 days, more than 40 persons died, most of them children. It marked the single largest Indian removal in Indiana history.

Although the Potawatomi had ceded their lands in Indiana to the federal government under a series of treaties made between 1818 and 1837, Chief Menominee and his Yellow River band at Twin Lakes refused to leave, even after the August 5, 1838, treaty deadline for departure had passed. Indiana Governor David Wallace authorized John Tipton to mobilize a local militia of one hundred volunteers to forcibly remove the Potawatomi from the state. On August 30, 1838, Tipton and his men surprised the Potawatomi at Twin Lakes, where they surrounded the village and gathered the remaining Potawatomi together for their removal to Kansas. Father Benjamin Marie Petit, a Catholic missionary at Twin Lakes, joined his parishioners on their difficult journey from Indiana, across Illinois and Missouri, into Kansas. There the Potawatomi were placed under the supervision of the local Indian agent (Jesuit) father Christian Hoecken at Saint Mary’s Sugar Creek Mission, the true end point of the march.

Historian Jacob Piatt Dunn is credited for naming the Potawatomi’s forced march “The Trail of Death” in his book, True Indian Stories (1909). The Trail of Death was declared a Regional Historic Trail in 1994 by the state legislatures of Indiana, Illinois, and Kansas; Missouri passed similar legislation in 1996. As of 2013, there were 80 Trail of Death markers along the route: they were located at the campsites set up every 15 to 20 miles (a day’s journey by walking), in all four states. Historic highway signs have been placed along the way in Indiana in Marshall, Fulton, Cass, Carroll, Tippecanoe and Warren counties, signaling each turn. Many signs have been erected in Illinois and Missouri. Kansas has completed placing highway signs in the three counties crossed by the Trail of Death.

Relationship To Pulaski County

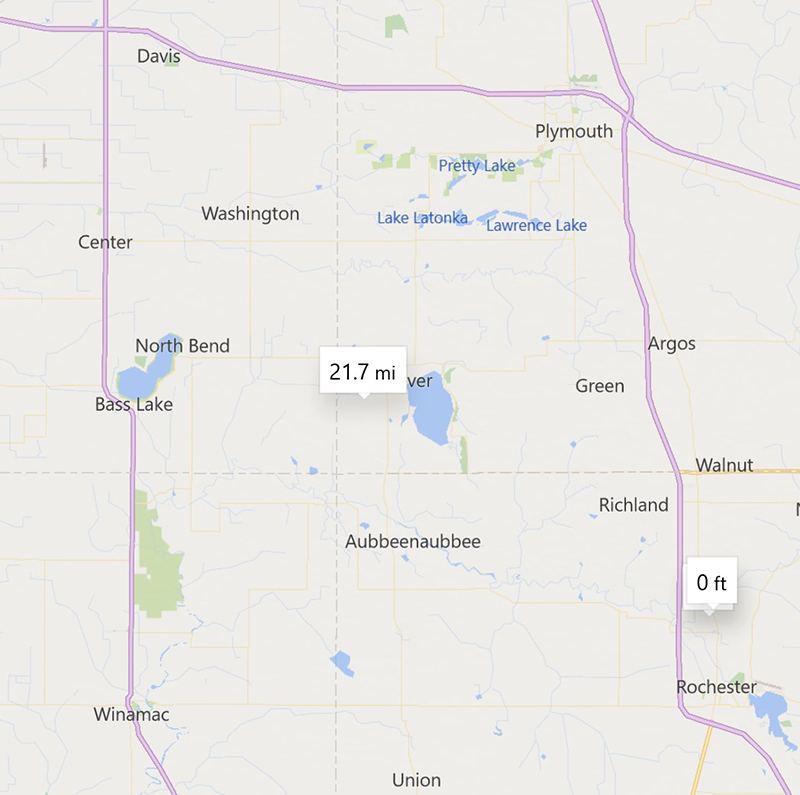

Included with this page are maps that show how close the beginning point of The Trail of Death is to Winamac. (Actually, to Star City, because that’s where the computer was when the maps were pulled up. Winamac is closer.)

The Potawatomi lived here. There are stories about them in the earliest recorded history of the region, The Counties of White and Pulaski Indiana, published by F. A. Battey & Co., Chicago, 1883. Stories are published in family histories, notably the Keller Family History from Monterey, self-published in 2004. We know they camped, fished, and hunted on the Tippecanoe.

They lived throughout the entire area, in the Potawatomi way, sometimes in one location, sometimes in another.

The Treaty of Tippecanoe, 1832, established a reservation for them on the Yellow River. The Treaty of Yellow River in 1836 disintegrated the treaty of 1832, taking away all of the rights and privileges established and banishing them to a land “west of the Mississippi.”

Those who refused to leave were forced to leave in 1838.

For reference, Pulaski County was named in 1835 and was established in 1839, when Winamac was named the county seat.

This is our history. The history of Pulaski County.

Stories

Stories are included here, written by descendants of those who were forced to remove to Kansas on the Trail of Death.

The Woods Are Lonely Now.

By Susan Joyce Dansenburg Campbell

An introductory message contained in the book, Potawatomi Trail of Death – 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell, Fulton County Historical Society, 2003.

Copies of this book are still available from the Fulton County Historical Society.

The story of the Potawatomi Removal from the Twin Lakes area south of Plymouth, Marshall County, Indiana to a small mission south of Osawatomie, Linn County, Kansas is a story well-documented in history. It can be found on microfilm records in the National Archives and documented in books and articles dealing with the history of the Potawatomi people. It can be found in history books, although merely annotated in some, that tell the story of places and people in the not-so-distant past, places whose names often bear remnants of the original Potawatomi name, people whose beliefs and actions formed the standards by which so many of us live today.

The Removal story is a story of people, people who lived on the land, planted and harvested their lands, built homes, lived, laughed, loved, gave birth and died. People who honored their Creator in ceremony and song, Christian and non-Christian alike. It is also a story of greed, of corruption and of fear, a story of expansion, of “manifest destiny” if you will.

But most of all it is a story of people. It is a story of families. And it is a story of my family. That is the story I want to share in this introduction.

Menominee, ogama (head man) of the village at Twin Lakes, Indiana, was a Catholic convert as were many of those residing in the village. The people of his village tilled the soil to feel their families, hunted in the nearby forests, built homes, and went to church. Menominee had invited the Black Robes, as the priests were often called, to come to his village and construct a mission church and that was done in 1834/35 according to the records of Rev. Louis Deseille (and contrary to the inscription on the stone tablet which marks the location on the lake shore, based on recollection). In 1835, the number of Indians estimated to live at Menominee’s village was 1500 living in a collection of approximately 100 wigwams, cabins and tepees. Menominee led his people in abstaining from alcohol and led them in worship and prayer twice daily. By the time Rev. Deseille visited Menominee’s village at the end of May 1835 the mission building was complete and the people of the village had made a gift of the mission building and 640 acres of land to the Church. On a list dated November 26, 1844 my fourth Great Grandfather Chesaugan’s name (also spelled She-Shaw-gin, Cheshawgan, Shehegon, Teshawgun, Shissahecon – when pronounced using a Potawatomi orthography these names all have a similar pronunciation) can be found stating that he received an annuity of $130.50 paid at Pottawatomie Mills (located on Lake Manitou, Rochester, Indiana), his portion of the annuities due the Potawatomi in the area for the year 1833. He is known to have traveled, to have been in Chicago, in Ohio, possibly as far north as Green Bay, Wisconsin. His name can first be found on the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, Ohio (though signed on his behalf by his brother). Then it is found on the September 30, 1809, treaty signed at Fort Wayne, Indiana; on a treaty signed in Chicago, Illinois, on August 29, 1821; and on a treaty signed “at the Missionary Establishment upon the St. Joseph, of Lake Michigan, in the Territory of Michigan” (wording taken from treaty) on September 20, 1828. Finally, his name is found on two treaties signed on the banks of the Tippecanoe River north of Rochester, Indiana, one on October 27, 1832, and a second dated March 29, 1836.

Records do not indicate that Chesaugan and his wife, Abita-nimi-nokoy, were Christian converts. It was customary when conversion took place that the church “assigned” a Christian baptismal name to the new convert (lists of names were kept for this purpose, the priest going down the list to the end and starting over at the top when the list ended). This was done to further separate a person from his or her tribal identity, a part of an assimilation process carried on into the present generation (information from survivors of the Catholic boarding school experience). In Chesaugan’s and Abita-nimi-nokoy’s case this was never done as far as I can determine. Certainly several of their children were converted, including their daughter, and my third-great grandmother, Sha-Note (given the baptismal name of Charlotte, she had married into a prominent Wisconsin trading family and lived with her husband Louis Vieux and children at Skunk Grove, now known as Franksville, Wisconsin until they were removed in 1836) and a son Basil (whose Potawatomi name was possibly Wassato).

And then came the Removal of 1838, referred to as the “Trail of Death.” I will not deal with all the historical facts and dates behind that; they are already presented within the text and need not be repeated here.

In 1838 Chesaugan and his family lived outside Chief Menominee’s village at Twin Lakes. He owned, in the Potawatomi way, eight acres of land (which in the currency of the day were valued at $40) planted in corn. He resided in a home much like other Potawatomi homes in the area, where he and his wife were raising their children. Their daughter, Sha-Note, my third great-grandmother, had married into a prominent Wisconsin trading family, the Vieus (in Kansas spelled “Vieux”); Sha-Note and her family had been on a removal from there to Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1836.

Chesaugan and his family did not join the Removal peaceably. According to the journal kept by Jesse C. Douglas, Chesaugan and his family “came into camp” outside Logansport, Indiana, on September 7, the fourth day of the Removal. In other words, as the volunteer militia went throughout the countryside rounding up the Potawatomi, they came upon Chesaugan and his family and rounded them up as well. The muster roll dated September 14, 1838, titled “Muster Roll of a remnant of Pottawatomie Indians of Indiana collected by John Tipton at Twin Lakes…” lists Chesaugan with one other adult make and two females (unnamed but possibly his son, Me-anco, whose name also appears on the muster roll) in his family group. Within a month following the removal a settler was heard to say, “The woods are lonely now.”

Of my family’s experiences on the Removal I have no stories. They were not passed down. By the twentieth century, through the experiences of boarding school and church, many Indian people were taught to be ashamed of their very being and fearful of their neighbors and so, out of a parent’s love for a child and the desire that the child not know fear or shame, the stories weren’t told. I do know that Chesaugan arrived in Kansas. On June 10 and again on June 17, 1843, his name can be found on letters, written from Potawatomi Creek, which request recompense from the Wabash Band Potawatomi as will as a request for Dr. P. Lykin to remain as their physician. A trading post record from October 28, 1846 shows a purchase of tobacco while an entry for January 15 shows the purchase of two shirts, sugar and a handkerchief (my thanks to Tom Ford for locating this information and sharing it with me). Archival records stored on microfilm (reel not catalogued) tell us that he appeared on the May 26, 1848, Fort Leavenworth annuity roll with his son-in-law Louis Vieux and seven of Louis and Sha-Note’s children. According to the recollections of Sophia Vieux Johnson (a daughter of Louis and Sha-Note) Recollections, her grandfather lived in a bark wigwam six miles from the family home outside Indianola, Kansas. This grandfather could only have been Chesaugan. Following that statement, there is no further word.

The militia who gathered the Potawatomi people together wanted to ensure that they didn’t return to Indiana and so many of their homes were burned behind them; their lands were eventually sold. In an address delivered before the Indiana House of Representatives on February 3, 1905, Representative Daniel McDonald stated that “the tepees, wigwams and cabins were torn down and destroyed and Menominee’s village had the appearance of having been swept by a hurricane.” They were compensated for their lands but what can compensate a person for a life?

I have no records of my family’s return to Indiana. Sha-Note died in Kansas in 1857, leaving behind several small children. Louis Vieux moved to farmland outside Louisville, Kansas, where he operated a toll bridge crossing the Vermillion River on the Oregon Trail. He married again twice and died on May 3, 1872; he is buried beside Sha-Note in the family cemetery on the farm east of Louisville, on a hillside overlooking the Oregon Trail. The cemetery is now a marked historical site.

Some of Louis’ and Sha-Note’s children took advantage of the allotments offered in Oklahoma and moved south after Louis’ death; my family returned to Kansas, where I was born. Although the custom of giving Potawatomi names continues in my family, the stories and the culture were largely put away, from what I can tell, until the 1970s. I was fortunate to discover clues left behind by my Grandmother Gracia Wade Dansenburg, great-great-granddaughter of Louis and Sha-Note, who passed over in 1970, and to have the help of family members in unwrapping these clues. Grandmother was sent to boarding school, attending Chilocco Indian School south of Arkansas City, Kansas, where it stands today. She understood the prejudices of her time but also understood the value of knowing your heritage She saw to it that as a child I was enrolled as a member of the Citizen Band Potawatomi (since 1996 the Citizen Potawatomi Nation), and it is because of her that I became interested in my Potawatomi heritage and started asking questions and looking for the clues she left.

What is the inheritance of the Removal? People who, in many cases, no longer know their language, their spirituality, their traditions, their arts. Who had these taken away from them, often by force, always by intimidation. There are those who joined together and kept these things intact and I honor them. I have met some of these Tradition carriers and have the highest respect for them. I give them my deepest thanks for sharing with me what they have. I have met those who have lost their identity, who have chosen, or had the choice made for them, to not remember who they are. It is my belief that they have lost much and I am sad for them.

As for me, I have been active in the recovery of our language, for it is my belief that within our language is our identity and without this we are no longer Potawatomi. I am active in the recovery of our arts, the beading and quill work our Ancestors did in the Great Lakes. And I am active in the preservation of my family’s history, through genealogy and the study of the history of the Potawatomi people.

In closing, I encourage you to discover you family’s stories and to share them with your children, to celebrate who you are, to celebrate the person who walks beside you, and to celebrate the person who lives next door.

A Survivor’s Story

From Potawatomi Trail of Death: 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell, Fulton County Historical Society, 2003

The following account is taken from O-go-maw-kwe Mit-i-gwa-ki (Queen of the Woods) by Chief Simon Pokagon, published in 1899 by C. H. Engle, Hartford, Michigan. A copy of this volume is found in the Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan. The text is to be found on their website, and is offered here with their permission. It is rare to find a Potawatomi account of the Removal of 1838 and we are grateful for their kind assistance. The story is told by Ko-bun-da, wife of Sin-a-gaw.

On the morning of that sad day at Twin Lakes, of which you speak, Sin-a-gaw, my husband told me that a stranger had been around, informing all the Au-nish-naw-bay-og (Indians) that our Christian priest wished all the tribe to meet him at Au-naw-ma-we gaw-ming (wigwam church), and desired me to go with him. But being au-keezee (sick), I remained at home. He faithfully promised me he would be back by the middle of the afternoon; but night came on, and neither he nor any of those I had seen going to church in the morning had yet returned. I felt impressed, deep down in my heart, that something awful had happened.

As I was sadly brooding over my thoughts, the door was wide open flung, and in came a little boy of the white race, who was a playmate of au-nish-naw-be o-nid-gan-is (Indian children), and who loved Sin-a-gaw, my husband, and me. As he rushed into our wigwam, all out of breath, he was crying, “Murder! murder! murder! O dear, dear!” He could say no more, falling exhausted on the floor. In a few moments he raised up, and stammered out, “O dear, dear! Lots and lots of white men I never seed before, all dressed in blue, have got all the Injuns in the church tied together with big strings, like ponies, and are going to kill all of um. Oh dear, dear! Do run quick and hide!” I said, “Hold on, Skiney. Do tell me if you saw Sin-a-gaw among them?” He replied, “O dear! Yes, me did; and me hear somebody say, “Skiney, come here,” and it was Sin-a-gaw. And he talk low, and say to tell you to hide in the big woods a few days, then go to the old Ot-ta-wa trapper’s wigwam, and if he not get killed, meby he get loose and find you. Do run quick! Dear, dear, they will get us! Me do wish I could kill em all.” I gathered up what few clothes I had and left our home, never to return. I ran across the great trail to your wigwam; no one was there. I heard several going past on the run. I heard some one speak in a heavy voice. It was Go-bo. I never heard him talk excited before. He said the whole country was alive with white warriors catching Au-nish-naw-bay-og, to kill or drive them toward the setting sun. All doubts of Skiney’s story were now removed. I ran north into a desolate swamp, which I had been taught from infancy was the home of jin-awe (rattlesnakes) and maw-in- graw-og (wolves), and there hid myself in the hollow of a fallen sycamore tree. It was an awful ne-tchi-wad te-be-kut (stormy night); wolves howled in the distance, as if following on my track; me-she-be-she (a panther) near by me screamed like a woman in dire distress. In the morning Loda, that girl was born! [the narrator was pregnant. Loda was her daughter.] I there remained one week, keeping aw-be-non-tchi (the infant) wrapped up as best I could. On the morning of the seventh sun I started northward to find the old trapper. I was weak and hungry, as all I had eaten while there was a small piece of jerked venison not larger than my hand, and a few beechnuts; but, thanks to the Great Spirit, I found in my journey an o-me-me (a young pigeon) so fat it could not fly. I sat down on a log and ate it raw. It tasted good, an gave me strength. In four days I reached the old trapper’s wigwam, where myself and child were kindly cared for. I there first learned the fate of my people, and was told tchi ki das-sos (that you were trapped) in the church with many others, and driven far westward. Late in wintertime my husband returned, and found my and our little one. He had traveled on foot and alone across the great plains from far beyond the “father of waters,” [Mississippi River] and was so broken down in health and spirits that he seemed all unlike himself. He sought to gain new life by drinking “fire-water” more and more; but alas, in a few years it consumed him, and he faded and fell, as fall the leaves in autumn time.

Walking in Her Footsteps

By Eileen Pearl

From Potawatomi Trail of Death – 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell, Fulton County Historical Society, 2003.

Copies of this book are still available from the Fulton County Historical Society.

Introduction: In September 1838 nearly a thousand Potawatomi Indians were forcefully removed from their homes in Northern Indiana. Many were converts to Catholicism and were accompanied on their march to Kansas Territory by a priest, Fr Benjamin Petit. Fr Petit kept a diary and from that we know the stops and also a report of the deaths which occurred during the two and one-half month trek to Kansas.

Soldiers chained three Potawatomi chiefs in wagons so that the people would follow. Soldiers on horseback and with wagons of supplies then forced the Indian men, women, and children to walk the more than six hundred miles to Kansas Territory. As many as 40 people died on the route due to the harsh conditions, lack of clean drinking water, and disease. Father Petit also became very ill before they reached Kansas and died a few months later at the age of 27 years.

Due to the many deaths, this forced removal has been named the “Trail of Death.” In 1988, 1993 and 1998 a commemorative caravan has re-enacted the trail by visiting each known campsite of 1838. Memorials have been placed at most sites where the trail passes through Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. Led by historian and organizer Shirley Willard and husband Bill, the caravan consisted mostly of descendants of those forced to walk on the “Trail of Death.”

As the wife of a great-grandson of a young girl on the trail these were my visions as I accompanied my husband and two of his family members on the 1998 canvas.

A group of 900 to 1,000 Native American men, women and children are trying to find a place for each family group to settle in for the night. This is taking place near a stream so water will be available. Unfortunately, this Fall of 1838 water is scarce and what they can find is sometimes contaminated. Many are becoming sick since leaving their homes along the Tippecanoe River. Many are dying, including children. Small, unmarked graves line the trail where families are forced to leave their little ones behind forever.

As I stood at the campsites in Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas my mind’s eye could see the activities of 160 years ago. Small fires burning here and there. The old huddled in blankets against the evening chill, their feet sore and swollen. The healthy children playing together, squealing with delight as they chase one another across the grassy field. The little sick ones being carried or held. Mothers with looks of despair on their faces.

Little Equa-Ke-Sec, possibly six years old, is helping with the babies. There she is, carrying a chubby brown baby on her hip and leading a black-haired toddler by the hand. She must keep them away from the fire and the horses’ hooves. She stands watching as the soldiers unload a few provisions from the wagons and toss them into the campsites. Is it enough to feed that family? The soldiers seem uncaring, anxious to finish the job.

The horses stomp their feet and switch their tails, fighting flies. The children brush the flies from their eyes and mouths. The mothers realize that at this campsite, again, there is not water for bathing or washing clothes. The tiny trickle barely supplies their needs for cooking and drinking. Tomorrow they will move on, farther and farther away from their homes, their stores, farms and mills in Indiana and Michigan. Forced by order of the government to relocate west of the Mississippi they walk 15 to 20 miles a day, always with the soldiers leading, pushing, shouting orders.

I see the faces of the young men. Stoic, sullen, with downcast eyes as the soldiers bark orders. These are the soldiers who chained their chiefs. They must follow their chiefs. They have been promised homes when they arrive in Kansas territory. It seems they will never arrive. Day after day they trudge on. Moccasins are wearing thing. Yesterday one of their mothers died, tonight a baby is dying and there is no medicine, no time for gathering herbs to ease the pain. Tomorrow, they have been promised a day to hunt. They welcome the chance to bring fresh meat into camp and a respite from the daily trudging. Their wives will spend the day mending the moccasins and nursing the sick.

In Jacksonville, Illinois I see the excitement in the camp as all are groomed and best garments are pulled from bags and stretched out on the grass to remove wrinkles. The young men’s turbans are twisted over their dark hair. The young women put on beads and earrings. Their shiny black hair is pulled back and knotted stylishly. Little Equa-Ke-Sec has been bathed and her hair is brushed straight back from her face. Her eyes dance with anticipation. They have been promised extra rations if they make a good impression on the people of Jacksonville. As they enter the town square the city band is playing. Their red and white uniforms make them look grand. Townspeople gather to watch the march of Indians on foot, soldiers on horseback and wagons carrying supplies. Dogs are barking, flags flying. The kind people offer Tobacco and sweets. Equa-Ke-Sec can hardly believe her eyes.ers

I see Equa-Ke-Sec when they reach their “Promised Land” in Kansas. There are no homes as promised and for that inter of 1838 she huddles with the others ina makeshift shelter between two stone walls. But Equa-Ke-Sec is a sturdy little girl and unlike many of her playmates she survives.

For a time an elderly little nun named Rose Phillipine Duschene lived among her people. Theresa as a young child heard her as she prayed. Her people called Sister Rose “the woman who prays always” because she was praying when they awoke and still praying when they went to sleep.

My vision skips to 1849 and I see Equa-Ke-Sec as a young woman. She has taken the Christian name, Theresa. The kind sisters, Madames of the Sacred Heart, have taught her to sew and cook. They have taught her what young ladies needed to know to start a home. The Jesuit Fathers have helped Theresa’s family and nurtured their faith. In this year they are again making a move, this time north of the Kansas River to what is to become the St. Mary’s Mission. Here a church and a school are built as are houses for the Potawatomi.

Here at last her journeys have ended and I see a young woman being married in the log church to a young Irishman named James Slavin. He has come to the mission as a driver for Bishop Meige. Theresa and James Slavin have chosen to join the Citizen Band of the Potawatomi and have been allotted land in Pottawatomie County, west of what Is now Bellevue, Kansas. I see them as they build their house and work the land, happy in the knowledge that they will always call this land their home. Memories of the forced march when she was a small girl still linger with Theresa and she passes on the stories to her daughter, Mary.

Theresa Slavin was the great-grandmother of my husband, Jim Pearl. Her daughter Mary Slavin Doyle was his grandmother. Jim and I are fortunate to have been able to join others on a commemorative caravan to visit the campsites and relive this history of his family.

We did indeed walk in her footsteps.

Trail of Death Reflections

– Personal and Our Great Grandmother’s

By Robert L. Pearl and Sister Virginia Pearl, great grandchildren of Et Equa Ke Sec

From Potawatomi Trail of Death – 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell, Fulton County Historical Society, 2003.

We have traveled the Trail of Death from beginning to end, three times in the past 14 years. Each time it has been a deeply spiritual experience. Some outstanding reflections from the 1988, 1993 and 1998 Caravans are as follows:

People all along the way would come up to us and apologize to us who had ancestors on the original Trail of Death. They would ask forgiveness in the name of their own ancestors who were farming the land in 1838 when the Potawatomi walked along their creeks and rivers. Some would apologize for the Indiana and the United States governments that had proposed and executed the removal.

One profound experience was with Marvin Puzey from Fairmount, Illinois. Marvin was in his 80s in 1988. He told us how his grandfather would take him down by the river to show him the tracks of the Indian removal. His grandfather would say, “It was a mile long of Indians and it was wrong. They were so hungry they dipped their hands in the barrels of spoiled molasses outside the molasses plant, even if the rats were in the barrel.” Marvin said, “It was terrible – please forgive our ancestors who done such a terrible thing to your people. I have tried to help the teachers in the schools here, to teach the truth about the mile long of Indians.”

We would have tears of remembrance.

Remembrances of how all of the people would turn out all along the way always put us in awe. Crowds came out in Springfield, Jacksonville, Exeter, and many other places. Each time we have come, the Jacksonville, Illinois, High School band has come out to greet us. It is recorded in the history that in 1838 when the Potawatomi walked through Jacksonville that some very wise band director led his band to play for the tired and suffering Indian families in order to lift their spirits. The band truly lifted our spirits each time we have come.

Memories of classrooms of children who would come to the curbs to meet us and welcome us to their villages with their teachers and school administrators. This all allowed all of us to become more aware of the injustice of the removal. The injustice of driving the Indians west of the Mississippi River so white Europeans could settle in the Potawatomi territory.

We give Shirley Willard and her family credit for their original research and her unflinching efforts to communicate the truth of the atrocities of 1838. This has happened by the way she planned the Trail of Death Commemorative Caravans, during the reenactments of the Trail of Death every five years, and the follow up media awareness. Hats off to Shirley Willard, her husband Bill and their son and her staff. Our hears are forever grateful for your courage and love. Our family has adopted her family into our Band.

Other memories that loom high are our visits to the wee town of Exeter. The City Dads invite the whole county each time we come and roast three hogs to feed us all. It is a highlight of the trip. We are asked to bless the infants. Then five years later when we come, those children are in school and then pre-teenagers ten years later. What a gift these young families are to us.

One day when we were in Sidoris, Illinois, a student, Clint Kolb, came up to us and gave us an arrowhead he had found where the Potawatomi had set up an overnight camp in 1838. He said, “This belongs to your folks. I saved it for you until you came, and the land belongs to you also.” Clint was coming from his high school basketball practice. What wisdom he has for one so young. Thank you, Clint.

Allen Switzer from Covington, Indiana, told of how his great grandmother’s parents let her go down below the hill from their home and play with the Indian children the night they camped on their farm in 1838. No doubt our great grandmother played with his grandmother. What a neat connection!

Through the years as we were growing up, our mother, Florence Doyle Pearl, would often tell us about her Potawatomi grandmother Et equa ke sec, who had been on the “long walk.” That was what Mother called what we know today as the Trail of Death. I think she knew the term Trail of Death but it was too harsh to repeat those words, and too fresh n the hearts of the adults. Mother would speak of the Long Walk, and the “hardships” of the walk from Indiana and their Michigan homes to the Sugar Creek Mission in Kansas, and of the first winter at Sugar Creek. She would tell us about the cliffs. There were cliffs nested under the small hills beside the banks of Sugar Creek. Her family hung der hides onto the overhanging cliffs for shelter. That was the “New Home” until a more stable shelter could be built. She also mentioned how scarce the deer and rabbits were that first winter.

On the bright side, mother would always bring to or awareness that our grandmother had been taught her prayers by a very holy sister whose name was Mother Rose Phillippine Duchesne, while she was at Sugar Creek. When Mother Rose Duchesne was beatified, it was a deep delight for all of us. Yes, a Sister who had taught our great grandmother was on the way to be honored as a Saint in heaven. I can remember Mother’s joy.

The Jesuits and the Religious of the Sacred Heart provided Potawatomi translations for the hymns and prayers used in church services, and taught Potawatomi in their schools. There was a compassionate thrust to how the faith was conveyed. It seemed that Mother’s memory of the suffering were eased through prayer and sacrifices. The offering of the sufferings of the past “long walk” and the hard winters of Sugar Creek led the Potawatomi to the promised land of St. Marys, Kansas, a Potawatomi Reservation in 1848.

As we now remember, Mom did not desire to go to Sugar Creek where the Long Walk had ended and where her grandmother had spent ten years of her early life. Perhaps the suffering of the Trail had been so great and also because death had knocked at the door of her grandparents and several cousins during those Sugar Creek years. Perhaps it was not easy for her to think of taking a trip to such a place. Mother always taught us to live our lives “through Indian eyes,” that is, to protect our mother Earth so she would nourish those for the next seven generations following us.

Going on the Trail of Death Caravan brings forth for us the presence of all who suffered. At each dedication of a marker, the suffering seems to surface and for a brief moment we experience tears of gratitude. Gratitude for the faith and courage of ever Potawatomi, those who died on the Trail, and those who survived.

We are especially grateful for the beautiful Indian maiden, Et equa ke sec, our great Grandmother, whom we came to know as Grandmother Theresa Living. We are told that she received her name “Living” because she was one of the few children who survived. We give thanks to Grandmother, as a survivor, for her courage. We thank God for our faith, our heritage, and our family which has come to us through Grandma Theresa. May God grant that future generations see life “through Indian eyes.”

The Series

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe