Why Are We Still Asking The Question?

A friend of the Historical Society, Jon Chapman of Edward Jones, asked us to finally settle the question: for which Chief Winamac was the Town of Winamac named?

And he put his money where his mouth was. His gift led to the applications for grants that allowed the Historical Museum to add an interactive component.

And so, we researched and wrote a series of articles about the history of the indigenous populations of Pulaski County, starting with the Ice Ages and ending with … this article.

The struggle is real. It has been a contentious point for nearly as long as the town has held the name. While this has been a fun trek down the roads of history, the information is confusing and often conflicting.

We tried to get the answer from as close to the horse’s mouth as possible, speaking to John Kocher, a direct descendent of the man who supposedly named the town, John Pearson. Mr. Kocher did not know the answer. Apparently, mum was the word for that family, except for the following.

Dick Dodd, local historian, is quoted from the Pulaski County Journal, November 1961, regarding the naming of the town by John Pearson. “Nearly 100 years later, one of his sons, John, then eighty-four years of age, wrote that his father named ‘the new town of Winamac in honor of the great Indian chief Wynamack.’” Mr. Dodd continued, “The comment raises the question, which Winamac did the founder consider great?”

More on Mr. Pearson a little later.

Authentic Portrait / Sketch of Chief Winamac

An authentic sketch of Chief Winamac does not exist.

SIDE NOTE: One reference, a photocopied page with a handwritten note that stated it was from True Indian Stories by Jacob Piatt Dunn, 1909, stated a sketch of exists in Thatcher’s Indian Biographies. The author of this webpage located both of those books online. The Thatcher book is dated 1833. The books are on order (an original of the Dunn book and a Thatcher book reprinted in 1901). If there is, in fact, a sketch with appropriate citations, it will be shared on this site.

Two have been done locally. The sketch used by Alan McPherson and James Carr in their book, Notable American Indians, was developed in Winamac to commemorate National Air Mail Week, May 15-21, 1938. Another, published by Dick Dodd in the Pulaski County Journal, was created for a soup can label. This author does not know: a) why choose a Native American who lived before the Model T for an air mail stamp, and b) what kind of soup would be graced with a picture of Chief Winamac? Both questions will go into the hopper of confusion.

Winamac: What’s In A Name?

From the bylaws of the Pulaski County Historical Society, and just about any publication that speaks of the beginning of the organized county, “Pulaski County was formally organized May 6, 1839, when a group of men met at a log cabin and designated “Winnemack” as the “Seat of Justice.” “

So, there’s a name. Let’s make a list of all that we are aware of, starting with “our” name.

- Winamac (“our” name)

- Winnemack (the name as it was written in 1839)

- Ouenemek

- Ouinemeg

- Wenameac

- Wenamuch

- Wenaumeg

- Wilamet

- Winamek

- Winemac

- Winnemac

- Winnemeg

- Winnimak

- Wynamack

- Wynemac

This isn’t all of them. You’ll meet a few more if you read on. This only illustrates how confusing the name can be, that name, and the names of most Native Americans during the same period. It seems historians could only get it right when the Natives adopted a European name.

There are many reasons for the plethora of spellings. The lack of a written language on the part of the Potawatomi and the other Algonquian tribes. The influence of the French. The influence of the British. The influence of colonial government and later the US government. The practice used of spelling Native names in the way they were pronounced, in the language of whichever country was doing the pronouncing. The lack of care taken by the soldiers and/or scribes who noted the names of Native Americans at the signing of treaties.

The Confusion of Potawatomi vs Miami

All the Chiefs Winamac that we will discuss were Potawatomi, by birth or by adoption. On occasion you will find a reference to the Miami Chief Winamac. This author was surprised how often that reference appeared.

Dick Dodd had an answer for that, also, from an unpublished*** history of Pulaski County written by Judge John Reidelbach, who passed away in 1939. In Mr. Dodd’s newspaper piece, he quotes the Judge thus: (***At the time Mr. Dodd wrote his article, the book was unpublished. You can now find it at the Pulaski County Public Library.)

“For nearly seventy-five years local historians and pupils having to write term papers on Winamac have turned to an 1883 history of Pulaski County for source material. There they noted, ‘The county seat was named for a distinguished Miami chief known as Wynemac.’ Repetition of that sentence in centennial booklets, public speeches and club programs does not make it true.”

The history to which he refers is The Counties of White and Pulaski, Indiana, published by F.A. Battey in 1883. By the time this book was written, the village bearing the name of Winamac – known by a couple of spellings – was on the Wabash River west of Logansport. It is possible they fell into another trap described by Judge Reidelbach.

“After moving to the Wabash River area, Winamac resided among Miami Indians. This would indicate that he may have become affiliated with the Miami Indians after leaving the Potawatomies.”

The confusion probably came about because Winamac’s Old Village, which you will hear more about later, is on the north side of the Wabash River. The Miami lived on their reservation in the Miami County area, but many lived as far north as the south side of the Wabash River near Logansport.

The Man Who Named The Town

John Pearson is the man purported to have named the town. This first piece comes from Counties of White and Pulaski, Indiana, published by F. A. Battey and Co., 1883. Yes. The same book from above that mislabeled the heritage of Chief Winamac.

“Mr. Pearson was one of the earliest settlers of Pulaski County. He was born in Ohio about 1813, and in 1838 came to where Winamac now stands. He soon became prominent in the affairs of the young county, and for upward of twenty years filled the offices of County Clerk, Auditor and Recorder. He was popular with the Indians as well as the white settlers.”

And from another section of the book:

“Pearson moved into the log cabin standing between the woolen factory and river but occupied it only while he was building a larger and better log building, into which he moved in November 1838. He began to entertain travelers, and his log dwelling was soon known as a “tavern.” He obtained some $200 worth of goods and notions, selling the same to the few settlers and to Pottawatomies, who often came to trade cranberries, maple sugar, venison and trinkets with him.”

Side Note: This was probably not the only tavern in Winamac, and stories are inconsistent, but one story states that the son of Potawatomi Chief Aubbeenaubbee, Pau-Koo-Shuck, was killed in a fight at a tavern in Winamac. Pau-Koo-Shuck went west on the Trail of Death in 1838, but supposedly escaped and returned home. That would have put his death in 1838 or 1839, when Pearson’s tavern was open, and since he founded the town, it was certainly the first.. Other stories state the fight started in a tavern but he died later. Either way, it’s another story, and something to consider. Was John Pearson’s tavern the place of death for this famous son of a famous chief? (This son is famous for having killed his father, and …. well, it’s a long story. Go HERE and HERE to learn more. You’ll also get the story of the ghost at Lake Maxinkuckee that is purported to be that of Pau-Koo-Shuck.)

Another Story of John Pearson

A local story, written by William L. Starr in his memoirs, Winamac, A Flint Stone Found on the Tippecanoe, 1983, adds a bit more.

Possibly the most influential and enterprising of these early settlers was John Pearson. He was born in Miami County, Ohio, in 1813 and married at the tender age of fifteen to Edna Farmer. Like so many, he felt the urge to move west, so early in 1838 he loaded his belongings in a covered wagon, and with his wife and five children, ranging in age from one to nine, they set out, not knowing where their wanderlust would lead them. The trip was slow and difficult since there were virtually no roads, but by late spring they reached the banks of the Tippecanoe and fortunately found an abandoned cabin into which they moved. It was located on the west bank of the river at the foot of what is now Spring Street. The cabin proved to be too small for his large family, so he soon built another more suitable, further north near the bend of the river.

John immediately became friendly with the Indians and began trading with them. Eventually he opened a store in his home where not only the Indians, but other settlers came to barter and to visit. As a result, his home became known as the “tavern.” He apparently had some means because by 1839 he had taken possession of the south half of section 11, Monroe Twp. And part of the SW1/4 of Section 12 where his cabin stood and together with four other men secured the western part of Section 13 and the eastern part of Section 14. This constituted about 1,000 acres and included all of what is now Winamac plus some surrounding land.

The story goes on to tell how the town was surveyed and platted and the county organized, until it gets to this point:

Legend has it that Chief Winnemack was a distinguished Miami Indian who fought with Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1812 and subsequently was buried near where the Methodist Church is now located. The change in the spelling can only be explained by these early settlers and they are not talking.

So. Let’s dissect that story a bit.

Mr. Starr’s story contained a few factual errors, including the part about Chief Winamac being a Miami Indian. Also, he seems to have chosen the Chief Winamac that supported the British in the War of 1812. That he made a choice is not a problem. It appeared he did not know there was a choice to be made. He shared yet another local tall tale, that Winamac was buried near the Methodist Church.

But it was a nicely written story. And it contained a breadcrumb or two.

Pearson’s Journey to Winamac

We know more about Pearson’s journey to Pulaski County from John Tipton. Tipton commanded the militia unit of “yellow jackets” at the Battle of Tippecanoe. By the end of his service during the War of 1812, he had been promoted to Brigadier General. He was elected to the Indiana General Assembly in 1819, and in 1831 to the office of US Senator from the state of Indiana, serving until 1838. He was appointed as a US Indian Agent and was selected to lead the militia in removing Menominee’s band of Potawatomi in 1838. Tipton would have been familiar with both of the Chiefs Winamac of the War of 1812 era. He would also have been familiar with any other Potawatomi named Winamac that might live in his area of interest, namely the Logansport, Cass County and Pulaski County area. We will quote from the Tipton Papers, Vol. III, 1834 – 1839, page 643. The following is excerpted from a letter written by John T. Douglass to Tipton on June 20, 1838.

Yesterday I purchased four fifths of the interest that Willis and his partner Graffes had in the Town site in Pulaski County they sold to a man from Ohio by the Name of Pearson and he immediately sold to me for the use of our Company. I suppose you are apprised of the members of the Company Yourself Wm. Polke Jesse Jackson & my self & John Pearson. Judge Polke is to buy Shotwells third and Mr. Pearson is to have an equal interest in that so that the whole company is to own the same interest. Pearson will move there in July and open a Public House each one’s share will amount to say 5 hundred and fifty dollars.

We want you if Possible to have the office moved there by the 1st of Augt. We can have buildings put up by that time from the reception of the officers and on the 20th of that month at the same time of the land sale we had better have a sale of lots in order to get money to meet our purchase.

How Would Pearson Have Known Any Chief Winamac?

Pearson arrived in the place that would be platted as Winamac in 1838. By all accounts, the last Chief Winamac to be in serious contention for the name died in 1821. You will hear more information below, but here, we offer a breadcrumb or two.

First: we do not know for certain how Pearson traveled from Ohio to Indiana, but if he came from Miami County, as noted by Mr. Starr, his route would have led through Logansport. It is known, from the Tipton Papers, that his business partners, including Mr. Tipton himself, came from the Logansport area. Their knowledge of the Chiefs Winamac could easily have been passed to him, as could their knowledge of other Natives by the name of Winamac.

There is another wrinkle to Mr. Pearson’s story and how the name might have been chosen. If you continue to read, in another section you will learn of Winamac’s Old Village on the west side of Logansport, and a particular road from Logansport to the area that would become Winamac, the Barron-Winamac Road. It is highly likely that Pearson traveled that road, and in so doing learned something about the name Winamac.

The area of Winamac’s Old Village eventually became part the Barron Reserve, land given to Joseph Barron’s family in grateful thanks for his service as an interpreter in the War of 1812. Mr. Barron would have been intimately familiar with two of the Chiefs Winamac from that era. To learn a bit more about that piece of property, go HERE. Mr. Barron lived in Logansport until his death in 1843, With the small circles in which these individuals traveled, and the relationship that Mr. Tipton and Mr. Barron would have had, it is more than likely Mr. Pearson came to know both men and have occasion to speak with them often.

Let’s move on to the theories about which Chief Winamac we’re talking about.

#1: Wilamet, an Adopted Potawatomi

In 1681, French explorer Sieur de La Salle was accompanied on an expedition by a group of Native Americans from several Algonquian tribes from New England. One of those natives, Wilamet (or Ouilamette or Wilamek) was appointed as a liaison between New France and the natives of the Lake Michigan region. He was adopted by the Potawatomi, and his name, meaning “catfish” in his language, was changed to a name meaning the same in the Potawatomi language. Let’s just use the spelling “Winamac.”

Before long, he was recognized by the French as the “chief” of the Potawatomi villages along the St. Joseph River in what is now the state of Michigan. This is something the French did on occasion. Winamac was not a traditional chief, but a man singled out to create alliances, or an “alliance chief.”

Wilamet/Winamac helped La Salle promote French policies while countering the Iroquois influence in the Lake Michigan region. (See our webpage regarding the French fur trade and the Beaver Wars.)

In 1694, a man named Ouilamek, which was probably the same Wilamet/Winamac, led 30 Potawatomi in an expedition under Antoine Sieur de Cadillac, the founder of Detroit, against the Iroquois. In 1701, Wilamet/Winamac, now listed as Ouenemek, and another prominent Potawatomi alliance chief represented the Potawatomi at the Treaty of Montreal, which ended the war with the Iroquois.

During the Fox Wars (1712 – 1733), a Wilamek was a leader of the Fish clan of the St. Joseph Potawatomi, putting him closer to the area that would become Pulaski County. Historian David Edmunds records this man as the same one that attended the 1701 treaty, although another historian claims a Wilamek of this era was of Sauk and Fox parentage who had married into the Potawatomi tribe.

I know. It’s hard to keep up.

#2: Supporter of Tecumseh and Allied with the British in the War of 1812

This Chief Winamac is known to have raided the Osage (unsuccessfully) in 1810. Returning from the raid, while still in Illinois, his party stole horses from white settlers. The settlers pursued the raiders, and the Potawatomi tribe attacked, killing four men. Governor Ninian Edwards demanded that the Potawatomi surrender the raiders, but chief Gomo informed U.S. officials that the raiders had gone to Prophetstown in Indiana.

At this point, this author will assume the reader is familiar with Tecumseh’s War, which preceded and ran concurrently with the War of 1812, but a nutshell version is given here.

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who brought Native nations together around his brother’s teachings to fight against further erosion of Native lands to US settlers. His brother Tenskwatawa (ten SQUAT a wa) – also known as The Prophet – believed Natives had angered the Master of Life. Natives had become reliant on American goods, such as alcohol, iron cookware and guns. He advocated a return to the traditional Shawnee way of life. By 1811 there were some two dozen Indian nations following Tecumseh, but the support was not exclusive. Tribal leaders were split. To have any chance of protecting their lands against the US, the Tecumseh Confederation needed an alliance with Britain.

Indiana Territorial Governor William Henry Harrison, pursuing his agenda of taking all Native lands and decimating the tribes, used the excuse of responding to settler complaints of Indian raids to march on the village of Prophetstown. It should be noted that the “raids” were conducted on land that was several years away from a treaty. The land was “owned” in the Native manner. The settlers were trespassing.

Tecumseh was not ready for armed opposition. He had not expected it, nor had he made aggressive moves in that direction. He was away, recruiting allies, when Harrison’s army left Vincennes and arrived at Prophetstown. Tenskwatawa was a spiritual leader, not a warrior. He accepted Harrison’s invitation to meet the following day and spent the night praying.

The war chiefs of the various tribes of the village argued through the night and eventually agreed to attack before the meeting could take place. They conducted a surprise attack, but Harrison’s forces held firm. After defeating the combined tribes, they burned Prophetstown, destroying the food supplies stored for the winter.

From the book True Indian Stories by Jacob Piatt Dunn:

There has been some contention as to the intent of the Indians, … but the truth was probably told later by White Loon, one of the leading chiefs present. He said that there was no intention to attack until the Potawatomi chief Winamac arrived and insisted upon it. A council was convened and most of the chiefs opposed attack, but Winamac denounced them as cowards, said it was now or never, and threatened unless the attack was made to withdraw and take with him the Potawatomi, who formed about one third of the town. Then the attack was agreed to. White Loon, Winamac and Stone Eater were put in command.

Hold this one thought for later discussion. It has been documented in many ways that Winamac “arrived” that night.

Telling the story in order, in August of 1812 (from August 8 through 15, the battle being on the 15th), there is some confusion as to this pro-British Winamac being one of the Potawatomi involved in the Battle of Fort Dearborn in Chicago. In fact, Winamac took credit for the battle. He was not among the warriors that are noted in history as being involved in the attack.

This Chief Winamac appears later that same month allied with the British at the siege of Fort Wayne. He appears later yet as a scout for the British under British Indian Agent Matthew Elliott. On November 22, 1812, Winamac was with a scouting party that captured several Natives allied with the US, including Shawnee Chief Logan, for whom the town of Logansport is named. On this day – accounts differ as to what happened – during an exchange of gunfire, Winamac was killed and Logan was mortally wounded.

From the Indiana State Library, in a letter to Richard Dodd of Winamac dated September 12, 1961, a biographical sketch was given of this particular Chief Winamac.

A principal chief of the Potawatomi in the period of the War of 1812. He was one of the signers of the noted treaty of Greenville in 1795, and of others in 1803 and 1809. In this last treaty, concluded at Ft. Wayne, the Miami, Delaware and Potawatomi sold a large tract of land in central Indiana. This so provoked Tecumseh that he threatened the life of Winamac, but there appears to have been a speedy reconciliation, as we find Winamac leading the warriors of this tribe at the Battle of Tippecanoe two years later. In the War of 1812, he, with most of the Indians of the central region, joined the British side. He claimed to have caused the massacre of the surrendered garrison of Ft. Dearborn, Chicago, August 15, 1812, but the actual leader in the affair seems to have been Blackbird (not to be confused with Black Partridge, a friendly Potawatomi of the same period), another Potawatomi chief. Some three months later, November 22, Winamac was killed in an encounter with the Shawnee chief Captain James Logan (Spemicalawba), who had espoused the cause of the Americans in the war. The name appears also as Ouenemak (French form), Wenameac, Wenameck, Winemac, Winnemeg, Wynemac, etc.

Note: Other sources say the US-allied Chief Winamac was the signatory at the treaties of 1803 and 1809, sold the large tract (3 million acres) of land, and was threatened by Tecumseh. But this is the Indiana State Library. (They could be confused, too.)

And yet other sources confuse which Chief Winamac was the target of the death threat. Some sources say the US-allied Winamac, because he dared to advocate for the sale of Indian lands, and others say the British-allied Winamac, because he dared to speak truth to Tecumseh.

And yet another confusion is the information about Winamac being a signatory on the Treaty of Greenville. This is not the only source to say that, but the treaty itself notes a man with a name that could be interpreted as “Winamac.” The name is “Wenameac,” and he has signed as a Potawatomi of Huron. This author does not believe Chief Winamac belonged to the Huron Potawatomi. The error could be anywhere, including with this writer.

#3: Aide to General William Henry Harrison and Allied with the US in the War of 1812

What we know to be the truth about this Chief Winamac is that he worked with the US Government, notably as a “trusted aide” to Governor Harrison. Among his documented actions, we see inconsistencies.

- He worked as a “trusted aid” for Governor William Henry Harrison. As such, he carried much information from Tecumseh’s Confederacy back to Harrison. He apparently had a great deal of access to Tecumseh’s Confederation.

- In 1807, he, Five Medals and Topinabee asked the US government for agricultural help. The equipment that was sent was never used, as only these chiefs were interested in agriculture, not their people.

- Also in 1807, he attended a council at Fort Wayne to address President Monroe’s need for more land. When the other chiefs and the Miami refused to negotiate land cessions, it was Winamac who persuaded first the Miami and then the Potawatomi to agree to the cession. When 3 million acres were agreed to, none were lands of the Potawatomi, although Winamac received a generous share of the payment of the land. It was because of the discontent caused by this treaty that Tecumseh’s Confederacy continued to grow.

- Tecumseh denounced Winamac as a “black dog” for supporting US interests.

- When Governor Harrison marched on Prophetstown, this Chief Winamac rode with him. When they neared the camp, Winamac rode ahead to speak with The Prophet. It is said that he left Prophetstown to meet Harrison but was on the far side of the Wabash and passed him by, thus he was neither with Harrison nor The Prophet during the battle.

- When the war between the United States and England was declared, Winamac continued to support the Americans. He first led a delegation to the Lake Peoria villages seeking the warriors accused of raiding the settlements. He was ridiculed by the Potawatomi warriors and left, unsuccessful. (The Peoria Wars are mentioned in our webpage regarding post-Revolutionary wars: LINK.)

- He carried General William Hull’s orders from Detroit to Fort Dearborn (Chicago), ordering Captain Heald to evacuate. Some sources say it was because an attack was imminent, but the order related to supplies. The fort that had the fastest route to Fort Dearborn had been taken by the British, and General Hull worried they could not keep Fort Dearborn supplied. Winamac told Commander Heald that they must leave that day to save themselves. That’s one version. Another version states Winamac urged him instead to stay inside the fort. Winamac left the fort. He is not mentioned in the list of soldiers, militia, Native Americans, wives, and children that left Fort Dearborn, headed to Fort Wayne. Nor is he listed among the Potawatomi that attacked the travelers. (This battle is mentioned in our webpage regarding post-Revolutionary wars: LINK.)

- From Alan McPherson and James Carr, Notable American Indians, they say that “most sources” place this Chief Winamac’s death in 1921, but they do not name a place or cause of death. Others say he died in Fort Wayne. Judge Reidelbach said he died in Chicago. Three thousand Potawatomi gathered in Chicago in 1821 for treaty negotiations, but this author found no evidence Winamac was there.

The following account is taken from The Potawatomi Indians: The History, Trails and Chiefs of the Potawatomi Native American Tribe, by Otho Winger, Adansonia Publishing, 1939.

There has been much misunderstanding about Chief Winamac, because there were two Potawatomi chiefs by the same name. One was friendly to the United States; the other was bitterly opposed to the Americans. The latter was killed in 1812 in a fight with the friendly Shawnee chief, Captain James Logan. The subject of this sketch died in 1821. His village was on the Wabash River, eleven miles downstream from the mouth of Eel River, where Logansport now stands.

While General Harrison was governor of Indiana territory, Winamac was his friendly aid in getting the Indians to make adjustments of their lands. Harrison wrote that Winamac was “an open and avowed friend of the United States.” He was strongly opposed to Tecumseh. For this reason, he was marked for death by the Shawnees. At one time in council, Tecumseh poured out a torrent of abuse upon Winamac and threatened his life. Winamac coolly got his pistol ready and was undisturbed by the threats of the great Shawnee chief. Tecumseh accused Winamac of trying to persuade the Indians to sell their lands to the United States. Winamac reported all the plans of Tecumseh to General Harrison. At one time he attended a great council held at Pare aux Vaches, now known as Bertrand, Michigan. There the council under Tecumseh’s suggestions planned to kill all the old chiefs and enlist the younger ones against Harrison. Winamac continued to attend the Indian councils and at one time boldly told The Prophet that he lied. He must have had great influence to be so daring without being killed.

By some it was reported that he was one of the Indian leaders in the Battle of Tippecanoe. Other Indians said that he was not. Here again he probably was mistaken for the other Winamac who was strongly against the Americans at this time. The next year both of them were present at the massacre at Fort Dearborn. The unfriendly Winamac was one of the leaders. The friendly Winamac brought a message from General Hull of Detroit to Captain Heald and warned the captain not to trust the promises of the other Potawatomi chiefs.

Winamac signed the treaties at Fort Wayne in 1803 and 1809. After the war he signed the treaty of peace at the Rapids of the Maumee, and the Treaty of Paradise Springs in 1826. After his death, his village on the Wabash was included in a tract of land given to Abraham Burnett. His name is perpetuated in the city of Winamac, county seat of Pulaski County, Indiana.

Let’s unpack this a bit. Dr. Winger notes the US-allied Chief Winamac at the treaties of Fort Wayne in 1803 and 1809. The Indiana Historical Society notes the British-allied Chief Winamac at those treaties. He notes that both Chiefs Winamac were present at Fort Dearborn, but the British-allied Chief Winamac, although he took credit for the battle, is not listed among the warrior chiefs. And this Chief Winamac doesn’t appear on the list of those that left the fort on the way to Fort Wayne.

Also, in one paragraph, he notes that this Chief Winamac died in 1821, and in another that he signed a treaty in 1826. This incongruence is actually pushed by more than one source.

But the story is nicely written.

From the Indiana State Library, in a letter to Richard Dodd of Winamac dated September 12, 1961, in which a biographical sketch was given of the “Chief Winamac #2,” a biographical sketch was also given of this Chief Winamac.

Another Potawatomi chief of the same period, the name being a common one in the tribe. Unlike his namesake, he was generally friendly to the Americans and interposed in their behalf at the Ft. Dearborn massacre, although he was said to have been among the hostiles at Tippecanoe in 1811. He visited Washington several times and died in the summer of 1821. His village, commonly known by his name, was near the present Winamac, Pulaski County, Indiana. See Dunn, True Indian Stories, 1909, Thatcher, Indian Biographies.

The State Library may have assumed that “near the present Winamac” was an apt descriptor for “west of Logansport.”

This is another indication that the two above-named books, Indian Biographies and True Indian Stories, must be sought as a reference. Again, they are on order. This article is going online before the expected delivery date but will be updated as deemed necessary.

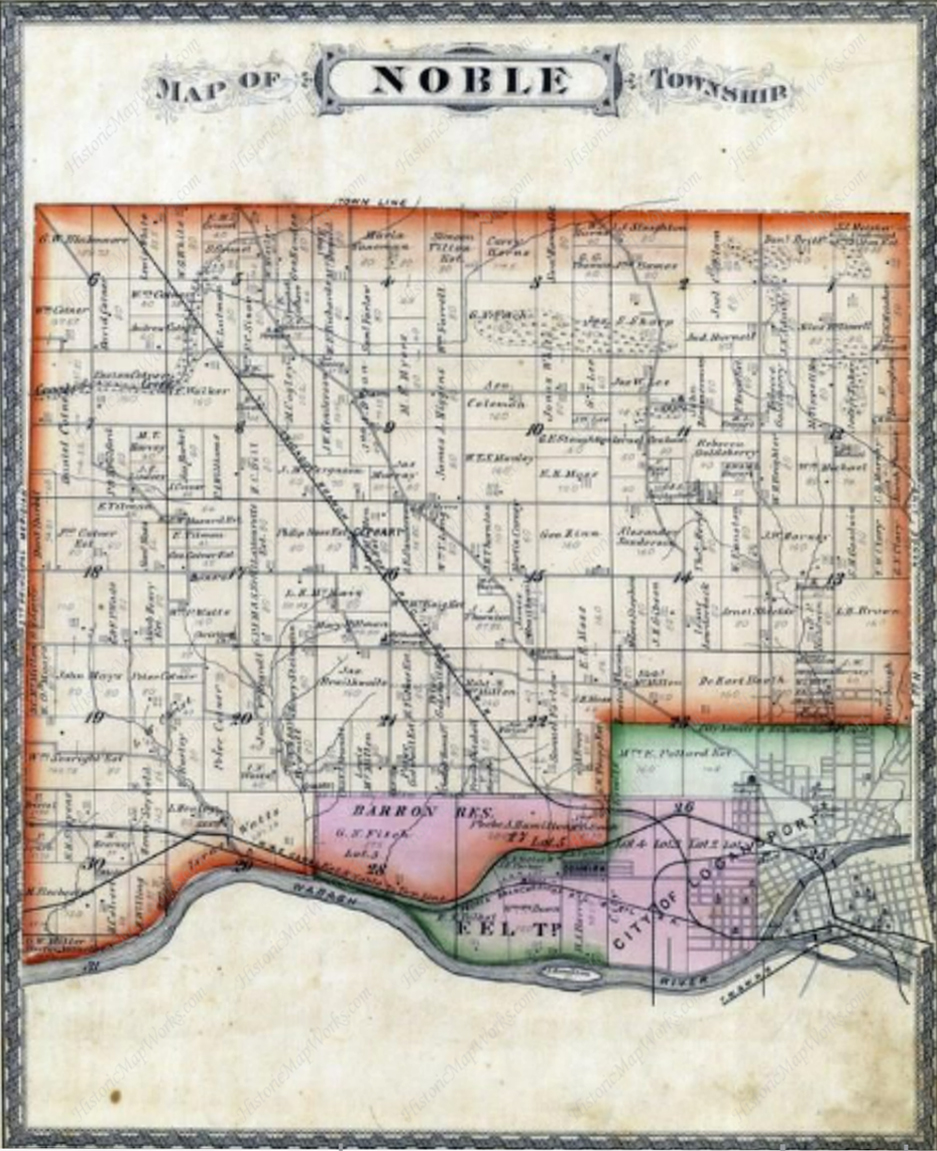

Winamac’s Old Village, Alluded To Above

George Winter is famous for his authentic sketches of Native Americans in the 1800s. In the book of his sketches, Indians and a Changing Frontier, the Art of George Winter, plate 367, page 194, is a sketch, “Near Winamack Scene Upon The Barrens-Winamack Road 1848.”

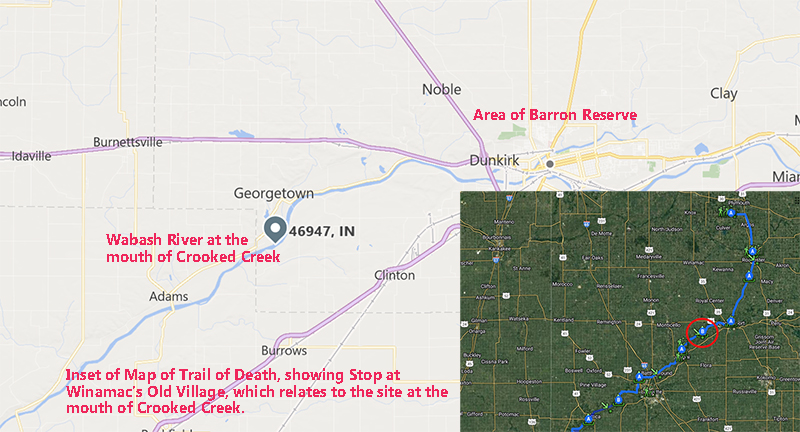

Asking a friend who used to work for INDOT, and hoping he might know something about this road, a gem of information was received. Not from his INDOT history, but from his historical and ancestral studies, he noted that the western end of Logansport where the Eel meets the Wabash was known as Barron Reserve. This was a large parcel set as a land grant to a French pioneer, Barron, who was an interpreter at both the Battle of Tippecanoe and the War of 1812.

My friend described a possibility of the road’s route thus: The land where US Highway 35 goes down to the bypass and fronts across from the Logansport State Hospital is all part of Barron’s land. This dates before 1838, the removal of Indians. This possible Barron Road would be roughly the Royal Center Pike along US 35 to Star City, crossing the river at Wassons Bridge or Deadman’s Hollow. The Hollow would have provided a convenient place to ford the river.

Another possibility for the road (see the photos of maps on this page) would have been a small road from where the Eel and the Wabash meet (Barron Reserve) that followed the Wabash River to Winamac’s Old Village. Winter’s non-color sketch appears it could be on a river, which could be the Wabash. The only information that is attached to it in the book of Winter’s art is “Scene on the Barrens. This is a representation of a primeval scene… The timber is sparse, having a park like appearance… a little prairie bordered by a strip of timber.” So, it’s not a river. It could be anywhere on the speculated routes.

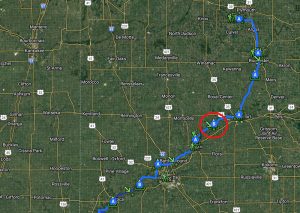

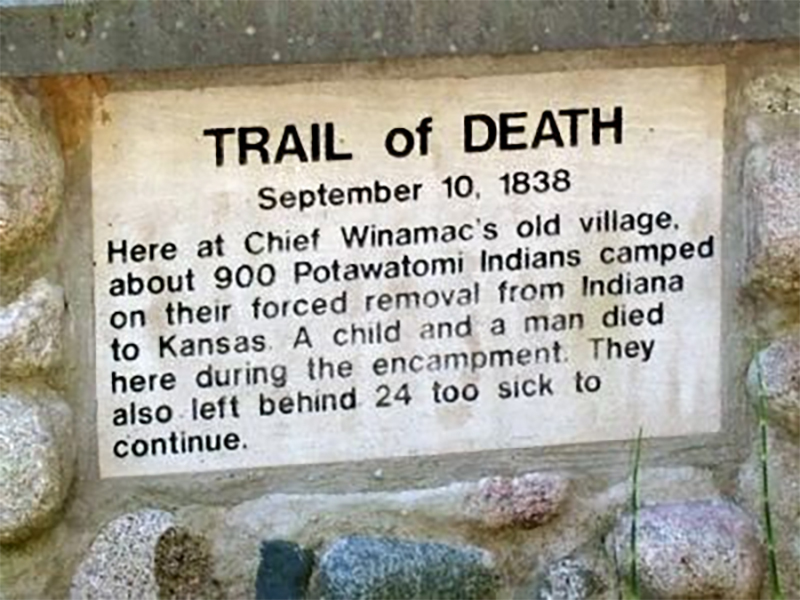

Winamac’s Old Village was a Potawatomi town and was a stop in 1838 on the Trail of Death. Potawatomi Trail of Death – 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas. These stops are noted in the early days of the march.

- August 30 – September 3: Twin Lakes, south of Plymouth in Marshall County, IN

- September 4: Chippeway on Tippecanoe River north of Rochester (traveled 21 miles)

- September 5: Mud Creek north of Fulton (9 miles).

- September 6 – 9: Honey Creek at Logansport (17 miles).

- September 10: Winnemac’s old village on Wabash River (10 miles)

- September 11: Pleasant Run, near Pittsburg (17 miles)

The map this author has of the Trail of Death does not mark this particular spot (naming the spots before and after), but Google is a wonderful thing. Found online was a map that could be drilled down, and a picture of that result is included on this page.

Another reference to this home comes from Alan McPherson and James Carr in their book, Notable American Indians. “After the war ended in 1815, documented accounts place a peaceful Winamac at home in his village along the Wabash River at the mouth of Crooked Creek, some ten miles west of Logansport, Indiana.” The description matches this map.

The newspaper article from Mr. Dodd, referenced above, speaks of Winamac’s home. “Some references to the more historic Winamacs note that the one associated with the town name had a reservation on the Wabash River in 1812. A local historian, however, indicated that the chief for whom the town is named lived in this vicinity (Winamac) until 1818. The late John Reidelbach, former judge of the Pulaski Circuit Court, was writing a history of the county at the time of his death in 1939. In his unpublished work, he stated that Chief Wynamack and his tribe lived in the vicinity of the present Winamac cemetery until 1818, when he established another village on the Wabash River.”

#4: A Person of No Importance

From Alan McPherson and James Carr in their book, Notable American Indians, comes another possibility. “Some writers believe the place name [for the town of Winamac] may have come via a fourth Winamac, who lived in a village there around 1818, existing peacefully and without historical note on a sandy west bluff overlooking the Tippecanoe River.” But it does not say where on the Tippecanoe this sandy west bluff might be. The river is 166 winding miles long. And to try to match it to Judge Reidelbach’s information about the village near the cemetery doesn’t work either. The cemetery is not near the river.

But across Riverside Drive from the United Methodist Church is a house that sits up high, on a sand hill, and it used to be higher. It is right next to the river. This covers all the bases of “living on a sandy west bluff” and the old wives tale of being buried under or near the church. This would hold true if it were “a” Chief Winamac or a person of no particular importance who shared the same name.

#5: Aide to General William Henry Harrison who was also a Double Agent during Tecumseh’s War and the War of 1812

John Nicholas of the South Bend Tribune LaPorte Bureau (Supplement September 23, 1979) wrote of the double-crossing spy theory.

The town of Winamac may have been named after an Indian double agent spy, a renegade of sorts.

It was away back in the days of the Indian wars in Indiana with the Potawatomi and Miami Indians that two “chiefs” named “Winamac” with a half dozen different ways of spelling it, started all the confusion.

One of the Winamacs was friendly (maybe) to the Americans and the second hated them with a passion.

From there, the article, while well-meaning, takes a loose interpretation of facts. For example, he mentions General William Henry Harrison in regard to the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, who later became Governor. Harrison was named Territorial Governor in 1800 and was still a Governor in 1811. He also mentions that Winamac was killed in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe. There is every indication that neither of the Chiefs Winamac perished in that battle.

But the premise is out there. Was Winamac in fact a double agent? Consistencies enough exist to make the theory plausible.

- Agriculture: Some sources say the pro-US Winamac pushed the use of agriculture, others say the pro-British Winamac did so.

- Signatory at Treaties of Fort Wayne, 1803 and 1809: Some sources say the pro-US Winamac signed the treaties, others say the pro-British Winamac did so.

- 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe: The pro-US Winamac accompanied Governor Harrison to Prophetstown and rode ahead – before the battle – to have a discussion with The Prophet. The pro-British Winamac arrived at Prophetstown “that night.” The pro-US Winamac left camp to rejoin Harrison but somehow road past the camp of 1,000 men. The pro-British Winamac was one of the warriors who led the battle against Harrison. (Enough wiggle room for the pro-US Winamac to leave Harrison, arrive at Prophetstown, put on his pro-British face, take place in the battle, and leave to rejoin Harrison at a later date.) (This scenario has been posed by others.)

- 1812 Battle of Fort Dearborn: The pro-US Winamac delivered a message from General Hull to Captain Heald, warning Captain Heald to leave. He is not heard of again in the story, either with the group leaving the fort or with the attacking Potawatomi. The pro-British Winamac bragged that he was a leader in the battle, but his is not one of the names listed in history as a Potawatomi leader.

- 1812 Incident with Captain Logan: The pro-British Winamac is killed and Captain Logan mortally wounded. The pro-US Winamac is still alive, being a signatory on at least two more treaties. Maybe.

- 1821 Death of pro-US Winamac: Supposedly Chief Winamac has lived peacefully in his village near Logansport, and “most sources” put his death in this year, with no manner of death, but death occurring possibly in Fort Wayne or Chicago.

- Treaties after 1812: Apparently, this Chief Winamac continued to sign treaties through 1826. A more likely explanation is that another Winamac, because it was a popular name, continued to sign treaties on behalf of the Potawatomi. This Winamac, or more than one Winamac, could have been signing them since the death of the pro-British Winamac in 1812. Which opens up the possibility that they “both” died at the hand of Captain Logan.

Governor Harrison’s Notes and Letters

The following note regarding Winamac is from Harrison Messages and Letters, Edited by Logan Esarey, Published by the Indiana Historical Commission, 1922.

Winamac was the chief of the Pottawattomies who opposed Tecumseh, but later led in the massacre of Fort Dearborn.

Harrison, himself, seems to believe that the pro-US Winamac, after delivering a message on behalf of General Hull, joined the battle on the side of the Potawatomi. How could he believe that his “trusted aid” participated in the battle unless he knew that his “spy” wore a different face with the Potawatomi?

And let’s just put this out there. How could the pro-US Chief Winamac spend so much time in Tecumseh’s company if Tecumseh did not believe him, at heart, to be aligned with the Confederacy?

What Have We Decided? Which Chief Winamac Is “Our” Chief Winamac?

#1: Wilamet, an Adopted Potawatomi

Unlikely. It is unlikely John Pearson was familiar with this particular chief from the 17th and 18th century.

#2: Supporter of Tecumseh and Allied with the British in the War of 1812

Unlikely. If Mr. Pearson was familiar with this Chief Winamac, either through his personal and business contacts or through his Native American friends, it would be unlikely that he would name the town he helped to found after the man who killed the man for whom the town of Logansport was named. (I hope you followed that sentence.)

He was friendly with the Native Americans of the area, which would have been from the Potawatomi tribe. It is possible he spoke with them about this Chief Winamac, but the Potawatomi that continued to live in the area had been supportive of the US government through all of the treaties, up to the Trail of Death.

#3: Aide to General William Henry Harrison and Allied with the US in the War of 1812

Probable. If Mr. Pearson was familiar with this Chief Winamac, either through his personal and business contacts (in particular an officer and an interpreter who worked with Governor Harrison) or through his Native American friends, it would be quite likely that he would name the town after this “great chief.”

His new Native American friends, if they spoke of him, would have spoken of him highly.

And let’s face it. Mr. Pearson was a pioneer in a still-young country, moving to a new county and establishing a new town. He would have been supportive of a Potawatomi Chief who supported this country in the War of 1812.

#4: A Person of No Importance

Possible. If a man named Winamac lived on a sandy bluff on the west side of the Tippecanoe, or if he lived in a village next to the cemetery, even 20 years before Pearson arrived, it is possible that the Natives he befriended were familiar with this man. And it is possible his personal and business contacts would have been familiar with him as well.

On the other hand, Pearson could have taken a political stance on the name. He could have become aware that the name Winamac was a common name, and if – as some say – the name was chosen to appease Natives, it’s possible this local man, great Chief or just a man, was the genus.

#5: Aide to General William Henry Harrison who was also a Double Agent during Tecumseh’s War and the War of 1812

This presents an interesting conundrum, but unlikely.

It is unlikely that in 1838 Mr. Pearson or anyone else living in the area was aware of the possible duality of one Chief Winamac being allied with both the British and US simultaneously. And if there had been a duality, “both” of the Chiefs Winamac from the War of 1812 era would have died in the gunfight with Captain Logan in 1812, and any Winamac living in the vicinity would have been some other, less important, Winamac.

But, if Pearson named the town for a “great chief,” it is likely he believed in one pro-American chief, and….. well, it would be nice if we had video of the discussions. Or audio. We’ll never know. It becomes a circular conversation.

Conclusion

We have 1) Unlikely 2) Unlikely 3) Probable 4) Possible 5) Interesting but unlikely.

So the winner is: #3: Aide to General William Henry Harrison and Allied with the US in the War of 1812.

Even though long deceased when John Pearson moved into the area, this would have been the man that caught the imagination of the pioneer.

Yes, Jon, we named a “winner.” But we conducted diligent research – and still had to make some best guesses – before naming that winner. Thank you for for sending us on this journey!

The Series

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe