The Two That Came Before

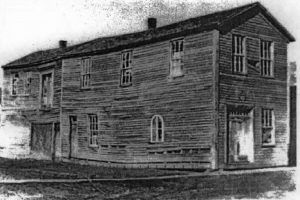

The Pulaski County Courthouse, built in 1895, is the third to be located on the courthouse square in Winamac and the fourth government center since the formation of the county in 1839. The first courthouse, a “good hewed log house” held both the first circuit court and a school. In 1843, the county commissioners began the construction of a frame courthouse on a donated lot but soon ran out of money; the building was finally completed in 1849. A second courthouse, a large two-story brick building, was completed in 1862. The county jail, a separate building, stood alongside it on the public square.

Improving The Seat Of Government

By 1890, talk again turned to improving the seat of government. The following “informal history” of the existing Pulaski County Courthouse was written by Linda Irving, the Pulaski County Historian:

Hear ye! Hear ye! Hear ye! Court is in session, the Honorable Judge George Burson presiding. Only the court isn’t in session and the judge isn’t presiding, because he can’t get into the court room. The door is locked. The date is 2 September 1895, and the judge is not happy.

Two years before Judge Burson had evaluated the old courthouse and written a report to the Commissioners condemning it. When the Pulaski County Commissioners met in January 1894, they decided to build a new courthouse. The project was not greeted with the greatest enthusiasm by anyone, except the judge.

The Commissioners Were Divided

Even the commissioners themselves were divided over the necessity of a new building. The old courthouse was only 32 years old, and while local opinion held that “it wasn’t very nice, or overly good, it was no worse than it had been for years.” It could do duty for a while longer. The argument put forth in support of the project was that the old building did not sufficiently protect county records, especially the land records. If anything happened to them, it would be a calamity of enormous proportion. It was further pointed out that interest rates were low and materials cheap. It was definitely time to build, On the other hand, taxpayers noted that the reason interest rates were low and materials cheap was that everyone was broke—including (and perhaps especially) them. Pulaski County was going through the worst financial depression it had experienced in years.

Crops had failed two years in a row and money was tight, but when it came to the protection of county records, the decisions of the Commissioners were final. They did not need public approval, and that was a good thing, because they were never going to get it.

Commissioners Play Games

Having decided to push ahead with a new courthouse, the Commissioners soon encountered a new problem. There were simply too many architects who submitted proposals. Twenty architects descended on the board on the morning of 5 March 1894, prepared to stay until all plans and specifications had been thoroughly gone over. That, combined with the Commissioners’ regular business, resulted in a mad house of activity.

Having decided to push ahead with a new courthouse, the Commissioners soon encountered a new problem. There were simply too many architects who submitted proposals. Twenty architects descended on the board on the morning of 5 March 1894, prepared to stay until all plans and specifications had been thoroughly gone over. That, combined with the Commissioners’ regular business, resulted in a mad house of activity.

After much discussion, all but six of the architects were dismissed. Then it seems that our three Commissioners were going to change their minds about building a new courthouse because they were immediately threatened with lawsuits. If they didn’t choose a design, they would be sued by all of the architects for the cost of preparing the plans.

The Commissioners pressed on and chose the design submitted by Rau and Kirsch of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who offered them an all-expenses paid junket to Waukesha, Wisconsin, to view a courthouse built from the same plans. That was when our Commissioners learned something it’s taken another century for Congress to get a handle on. Don’t accept gifts or gratuities of anything else that looks even vaguely like fun from people who want the taxpayers’ money.

Immediately, there was a lengthy petition filed, the chief charge of which was that “the Milwaukee firm had exercised rather an undue and unfair influence upon the board.” So the courthouse matter took a new turn, and, after deciding that the Wisconsin plans weren’t so good after all, the firm of A. W. Rush and Sons [A. William and Edwin A. Rush] of Grand Rapids, Michigan, was awarded the contract signed by Commissioners Maibauer and Hiland but not by Commissioner Welsh, who was rapidly becoming sick and tired of the whole things (and who didn’t want to build a new courthouse anyway, so there).

The Circus Continued

The circus continued, with the next act being the contractors. Seventeen bids ranging from $42,200 to $52,457 were received, and the contract went to the low bidder, Jordan E. Gibson of Logansport. Again there were objections. The architect said that the courthouse couldn’t be built for that little money. Auditor Bouslag said, “Let him try. It’s our tax money.” And the argument was on again for the rest of the day, and, after the Commissioners recessed for supper, it was continued down on the street corner. There were no blows struck, however, and Gibson did get the job.

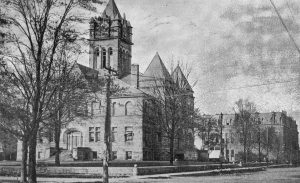

The building was to be 88 feet by 90 feet on the ground, 32 feet from the top of the basement to the roof and 106 feet from the ground to the top of the tower. It was to be built of the best Bedford, Indiana, limestone outside and brick inside. Steel lath, stone wainscoting in the halls, dead floors in the rooms, and tile floors in the halls were to make it almost fireproof.

It was to be completed by 1 September 1895. The contractor received the old brick courthouse, which had to be removed to make way for the new. The records and offices were moved to the second floor of the Vurpillat opera house, except for Recorder McKinsey. He said his game leg would never make it up all those stairs. Since the opera house was already overcrowded, no one objected to his moving to J. F. Yarnell’s office on the corner of South Market and Jefferson Streets.

Court was held in the old Holsinger hall over Hodson’s exchange at the corner of Monticello and Pearl Streets. It took only two days for the old building to come down and for work on a new building to begin. Huge slabs of stone, a foot or so think, was shipped in by rail and hauled on flat-top wagons to the public square. The heavy pieces were placed on strong trestles, where workers used hammers and chisels to cut and trim the pieces as prescribed by the drawings. Then they painted numbers on the reverse and awaited hooks from steam operated derrick that lifted them into specified places on the structure.

Even though construction was well under way, there was still grumbling in the ranks. There were complaints about workers getting the stone stained with clay—stains which could not easily be removed. There were complaints from the workers about low wages, and several went on strike and quit working. But as editor Gorrell of the Winamac Democrat] said, “$6.00 a week beat idleness by about 600 cents.” The men were easily replaced. Times were hard in Pulaski County.

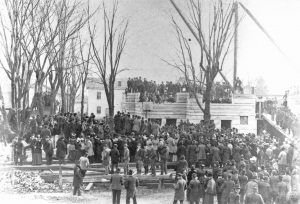

Cornerstone

The brightest spot of the year was the laying of the cornerstone on Tuesday, 7 November 1894. The newspaper headlines read: “IN PLACE!” The Corner Stone of the New Court House Laid with Imposing Ceremony – and Mortar. Winamac Masonic Lodge Turns from Speculative to Operative Masonry and Does the Job. . . . Beautiful Day, Large Crowd, Impressive Exercises, all Contribute to Make the Day Memorable.” There was even a parade. The Commissioners and a few others went first, riding in carriages followed by the G.A.R., the different grades of the city schools, each grade in charge of its teacher, several neighboring Masonic lodges, and two bands. A choir had been organized to sing at the appropriate place on the program.

One of the high spots of the day was when a copper box was placed in the corner stone. The valuable contents were a program of the county institute; a program of the teacher’s association and a full list of teachers employed hi the county; a photograph of the old frame courthouse built in 1849 and another of the brick building erected in 1862, a sheet of foreign stamps with the names of the Winamac Philately Society and a letter from Jonathon Werner (contents unknown); and a copy of the last issue of each of the Winamac newspapers.

There were between 2,500 and 3,000 people in attendance that day, and they all had a great time, except for the Winamac Republican editor, who complained about the seating arrangements. He couldn’t see what was happening.

Even Great Times Don’t Last Too Long

Unfortunately, even great times only last so long, and by the end of December a restraining order was filed against the commissioners for allowing a number of changes in the plans and specifications amounting to nearly $10,000 over the original contract total. They added a boiler, pumps and fittings, a well, an extra door to the boiler room, extra concrete, sewer pipes, etc., etc.

They were told to please restrain themselves from further improvements.

Which Brings Us Back…

Which brings us back to 2 September 1895 and Judge Burson. Even though the courthouse was completed—mostly—the commissioners had not yet accepted it. It was still in Contractor Gibson’s hands, so when Sheriff McKay went to open the courtroom door, he was turned away.

The court ordered the door opened via the crow bar route if necessary. After considerable talk that was mighty hot at both ends and not particularly cool in the middle, a truce was patched up. Gibson was assured he wouldn’t be held accountable for any damages and the door was opened. No crow bar was needed.

Courthouse Accepted

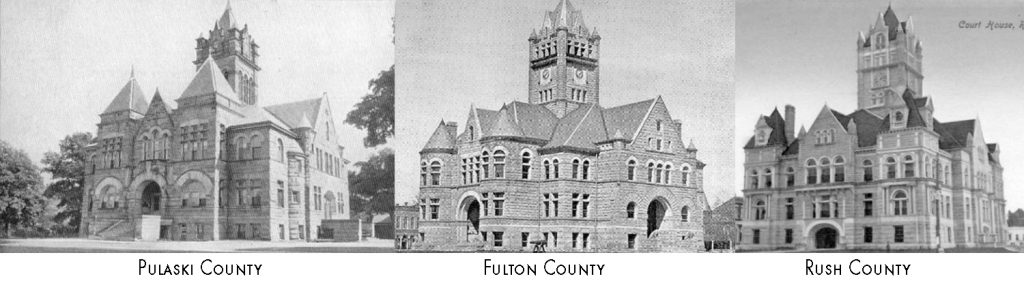

On 7 September 1895, the commissioners formally accepted the courthouse from the contractor for $52,179.90. Gibson promptly left town for Rochester, Indiana, where he laid [the Fulton County courthouse] cornerstone two weeks later.

An interesting sidelight to this whole affair is that the same architect who fought to keep Gibson off of the Winamac project recommended him for the Fulton County job.

The Rascals!

And the commissioners? The voters had the last word, and the word was, “Throw the rascals out!” And they did.

Unpretty Slabs

Ned Gorrell told a story that took place when the courthouse was completed. He was just a boy when two flat slabs, five or six feet square, appeared on the north front, one on each side of the main door. He recalled the curiosity with which the youngsters regarded these unpretty slabs.

Ned Gorrell told a story that took place when the courthouse was completed. He was just a boy when two flat slabs, five or six feet square, appeared on the north front, one on each side of the main door. He recalled the curiosity with which the youngsters regarded these unpretty slabs.

No one seemed to be able to tell why they had been left. Then one day some workmen put up a scaffold in front of them, and a clever workman climbed up to cut a huge face on each one.

In reply to questions, as Ned heard it, he said the faces “don’t mean a darned thing” but were carved merely because the architect had put them in his original drawing.

In reply to questions, as Ned heard it, he said the faces “don’t mean a darned thing” but were carved merely because the architect had put them in his original drawing.

Architecture

The Romanesque Revival style was a popular choice for Indiana courthouses during the last decade of the nineteenth century, with fifteen county courthouses in the style being built between 1886 and 1897. Three of these—Pulaski (1894-95), Fulton (1895-96), and Rush (1896-98)—were designed by A. W. Rush and Son. The Pulaski and Fulton County courthouses were built by Jordan E. Gibson of Logansport.

There are some similarities among Rush’s three Indiana courthouses, but his designs demonstrate an evolution in the interpretation of the Romanesque Revival style popularized by H. H. Richardson. The Pulaski County design is the simplest (and the least expensive when built), and the Rush County design the largest and most complex.

All three are built of rusticated Bedford limestone with carved stone details. The elevations of all three are symmetrical, with projecting central entries framed by arches, square bell/clock towers rising above the central crossing, and bands of rectangular and arched windows. The interiors, too, represent a transition from modest to lavish. On one end is Pulaski County’s abundance of natural oak woodwork; on the other end is Rush County’s abundance of Tennessee marble. Each of the three courthouses has undergone relatively little exterior alterations, most notably replacement doors and windows. The greatest degree of interior integrity is retained by the Pulaski County Courthouse, whose hall, offices, and courtroom are virtually unchanged.

Notes From The Commissioners

September 12, 1895 p44: In consideration of the payment of Five Hundred and twenty one ($521.00) dollars the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, We hereby guarantee the successful operation of the heating apparatus put up in the Pulaski County Court House by us in every respect and that it will warm the rooms and halls of the building at one and the same time to a temperature of 70 degrees F’ht when the outside is 0 degrees below zero and that it will be noiseless in operation and we agree to make good any defect that may appear during a period of 5 years.

September 23, 1895 p49: In relation to the proposal of the Hall Safe & Lock works for iron doors & shutters for Court House windows comes now the said Hall Safe & Lock company and present proposals as follow to wit…. And the Board after having examined said proposals so herby accept the same which are on file in the Auditor’s office.

In relation to the proposition of W.C. Vosburgh Mfg. Co. to furnish Electric light fixtures for Court House.

September 24, 1895 p50: In relation to the proposal of the Fenton Metallic Mfg. Co. to furnish fixtures for the vaults of the various offices in the Court house. Witnesseth. That for a consideration hereinafter named, the party of the first part agrees to furnish and deliver to said party of the second part in complete Cabinet Cases, and set the same in place, ready for use, in the various office in the new Court House at Winamac, Indiana on or before December 17, 1895….