As with every other chapter in this saga, we will concentrate on the wars, battles and aftermath that affected the Potawatomi. And again, this is not an in-depth historical review, but a summary. The summary will dwell primarily on lands ceded from Native American tribes to the United States. These conflicts are often referred to as the Eastern Woodland Wars.

Northwest Indian War 1785 – 1795

The US Army considers the Northwest Indian War the first of the United States Indian Wars. The US Army fought a united group of Native Americans, known today as the Northwestern Confederacy, sometimes as the Western Confederacy.

Centuries of conflict for control of this region preceded the Northwest Indian War. In the years preceding the Revolutionary War, the British had set aside this land as a reservation for Native Americans. After the War, the land was ceded to the United States with no mention of its Native American inhabitants. The treaty set the Great Lakes as a border between British territory and the US. It was known as the Ohio Country and the Illinois Country.

Before the War, new settlements by European American colonists and settlers were prohibited.

After the War, the US government was deep in debt.

Congress intended to raise revenue by selling land to American settlers. When the US opened the land for settlement, tribal leaders argued the lands were held in common by all tribes and that no land could be ceded without the consent of the confederacy. The confederacy included Iroquois, Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, Three Fires (Chippewa, Ottawa. and Potawatomi), Cherokee, and Creek.

George Washington, now President, refused to recognize the Native confederacy. He directed the Army to enforce US sovereignty over the territory, pursuing a policy of divide and conquer. The new territorial governor was instructed to negotiate new treaties without surrendering any lands and to acquire more land if possible. The governor was also tasked to undermine the Confederacy.

The US Army consisted mostly of untrained recruits and volunteer militiamen. The Army suffered a series of major defeats, including the Harmar Campaign (1790) and St. Clair’s Defeat (1791), which are among the worst defeats ever suffered in the history of the US Army. Eventually, General Anthony Wayne was charged with the task. He spent a year building, training, and acquiring supplies. After a methodical campaign in western Ohio Country, in 1794, he led the Army to a decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near what would become Toledo.

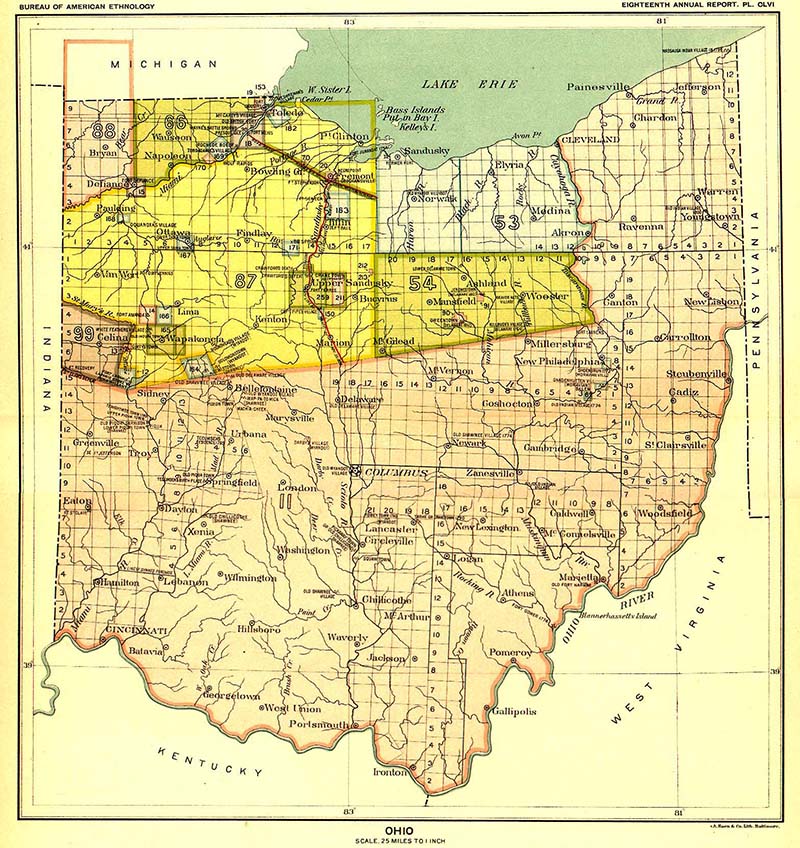

The defeated tribes ceded extensive territory, including much of present-day Ohio, in the Treaty of Greenville. The Jay Treaty led to the British ceding Great Lakes outposts to the US. After the War, large numbers of US settlers migrated to the Northwest Territory.

Five years after the Treaty of Greenville, the territory was split into Ohio and the Indiana Territory. In February 1803, the State of Ohio was admitted to the Union. The border between Ohio and the Indiana Territory closely followed the line of advanced forts and the Greenville Treaty Line.

Under President Thomas Jefferson, territorial governor William Henry Harrison began an aggressive campaign of native land acquisition. Native American resistance movements were unable to form a union matching the size or capability seen during the Northwest Indian War.

In 1805, Tenskwatawa (the Prophet) began a traditionalist movement that rejected US practices. His followers settled at Prophetstown in Indiana Territory, leading to Tecumseh’s War and the Northwest theater of the War of 1812.

United States settlement continued, fueling Indian removals and conflicts well into the 1830s. These include the Black Hawk War and the Potawatomi Trail of Death. Wisconsin, the last state fully located in the Northwest Territory, was admitted to the union in 1848.

The Treaty of Greenville 1795

The Treaty of Greenville ended the Northwest Indian War in Ohio Country and redefined the boundary between Native peoples’ lands and territory for European American community settlement. The Native American leaders who signed the treaty included leaders of these bands and tribes:

- Wyandot (Chiefs Tarhe, Roundhead and Leatherlips)

- Delaware (several bands)

- Shawnee (Chiefs Blue Jacket and Black Hoof)

- Ottawa (several bands)

- Chippewa

- Potawatomi (23 signatories, including Gomo, Siggenauk, Black Partridge, Topinabee and Five Medals)

- Miami (including Jean Baptiste Richardville, White Loon and Little Turtle)

- Wea

- Kickapoo

- Kaskaskia

Following their defeat at the decisive battle at Fallen Timbers, General Wayne had bargained with several key leaders in the Confederacy. Opposition to working with the US was led by Little Turtle, who eventually was the last to sign the treaty.

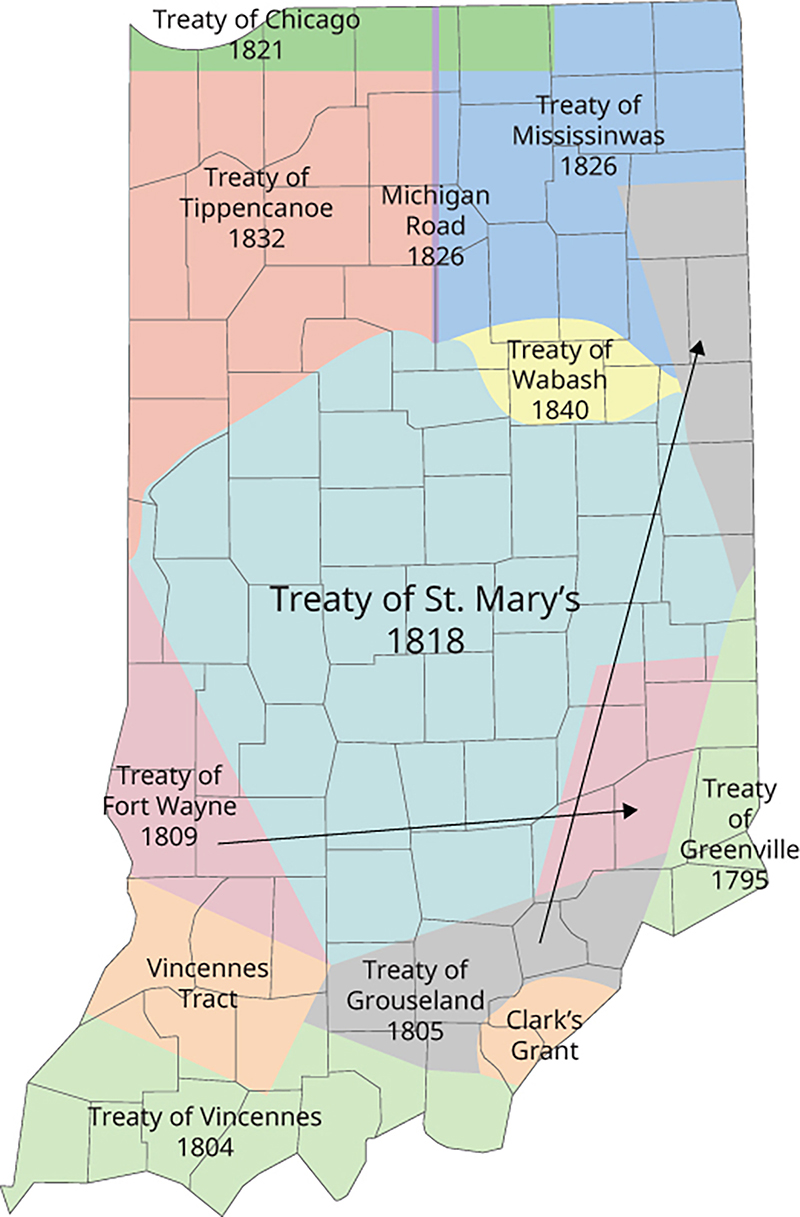

Treaty of Fort Wayne

In September 1809, Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami and Eel River tribal leaders signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, ceding approximately 3 million acres of land in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan for 2 cents an acre. The treaty ultimately brought an end to peace between the Unites States and many Native Nations, creating a divide that contributed to the start of the War of 1812.

President James Madison actively worked to acquire Native American land throughout his presidential tenure. Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison was therefore ordered to assemble all the Indiana tribes at Fort Wayne in September of 1809 to reach an agreement that would open lands for settlement south of the Wabash River. In his book The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire, R. David Edmunds wrote the Potawatomi “were led by Winamac, perennial friend of the United States, who earlier had assured Harrison that all the tribes would be willing to cede the lands. Notably absent were such other friendly chiefs as Five Medals and Keesass, who feared retaliation by their younger warriors if they agreed to a land cession.” The Miami were not supportive and refused to relinquish their land claims until Winamac and several Delaware leaders convinced them otherwise.

In return for Winamac’s efforts, the Potawatomi received an increased amount of trade goods, which many needed to overcome the recent harsh winters. Yet, the additional provisions failed to gain the approval of all Potawatomi. Instead, Winamac’s actions at Fort Wayne caused disharmony, and younger leaders became increasingly upset with his pro-American stance. Turmoil over land rights ensued, and less than three decades after signing the treaty, the government forcibly removed most of the tribes involved to lands west of the Mississippi.

Tecumseh’s War 1811 – 1815

The Battle of Tippecanoe is viewed by many as the first battle of the War of 1812.

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who brought Native nations together around his brother’s teachings to fight against further erosion of Native lands to US settlers. His brother Tenskwatawa – also known as The Prophet – believed Natives had angered the Master of Life. Natives had become reliant on American goods, such as alcohol, iron cookware and guns. He advocated a return to the traditional Shawnee way of life.

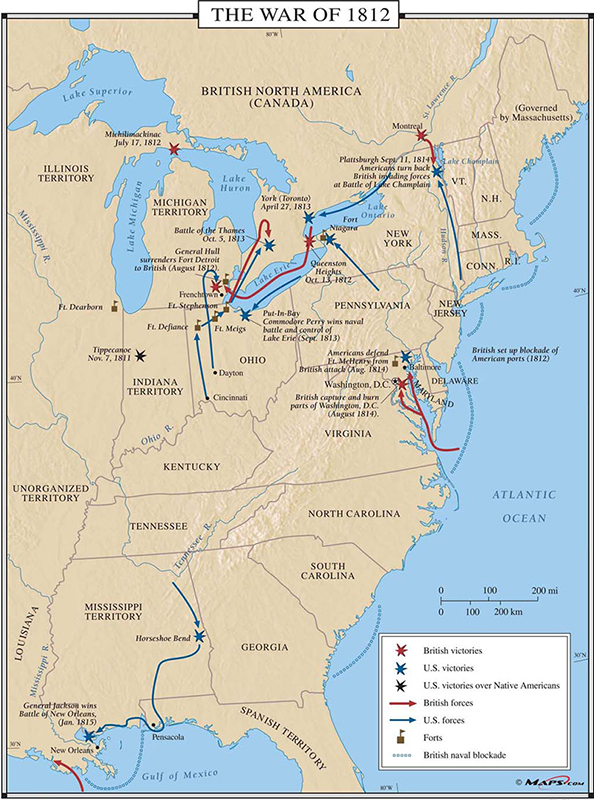

By 1811 there were some two dozen Indian nations following Tecumseh. To have any chance of protecting their lands against the US, an alliance with Britain was needed. That need became even more evident after the Battle of Tippecanoe when Harrison destroyed Tecumseh’s home base of Prophetstown.

Tecumseh’s Confederacy then fought alongside the British to protect Canada from the onslaught of American forces during the War of 1812. Had they not, Canada could look very different today. Tecumseh fought and won a number of battles against US troops around Fort Detroit. The Provence of Ontario, and probably a good part of the rest of present-day Canada, would now be part of the United States were it not for the Native warriors who overwhelmingly came to the defense of the British Crown in the first year of the War of 1812.

But Tecumseh’s defeat at the Battle of Thames in Canada in 1813 was the beginning of the end for Native nations. Tecumseh was mortally wounded; with his death his confederacy fell apart.

After 1815 Native Americans could no longer play what sociologists call the role of conflict partner – an important other who must be taken into account – so Americans forgot that Natives had ever been significant in our history. Even terminology changed. Until 1815 the word Americans had generally been used to refer to Native Americans; after 1815 it meant European Americans.

Potawatomi Involvement with Tecumseh’s War

Main Poc was a leader of the Yellow River villages of the Potawatomi. (Yes, the Yellow River that flows so close to Pulaski County.) Throughout his entire life, he fought against the growing strength of the United States and tried to stop the flow of settlers into the Old Northwest. He joined with Tecumseh to push the settlers south and east of the Ohio River, and he followed Tecumseh to defeat in Canada.

Main Poc was a warrior and chief with a near cultish following. This allowed him to build a strong relationship with both brothers. Ultimately, he convinced them to relocate from Ohio to an area near his own village in Indiana. After receiving permission from the other Potawatomi tribes of the region, the brothers moved to their new village near present-day Lafayette, Prophetstown.

Without Main Poc’s military support, the message of the brothers may not have caught the traction that it did. American Indian agent William Wells considered Main Poc as the “greatest warrior in the west … the pivot on which the minds of all Western Indians turned … (he) has more influence than any other Indian.”

On November 5, 1808, Main Poc traveled with Agent Wells and others to Washington D.C. Although Wells hoped the trip would help settle the Potawatomi and other Native group’s disdain for the government, Main Poc continued to dislike the United States. Main Poc met personally with President Jefferson and refused the suggestion that the Potawatomi should become farmers.

After returning to the Great Lakes region, Main Poc continued building a relationship with the Shawnee brothers. He was not present during the Battle of Tippecanoe, but after the battle, he traveled across Potawatomi, Sac and Kickapoo villages to help prepare them to join Tecumseh in his continued war against America. And, although again not present for the battle, he encouraged Potawatomi war chiefs to attack Fort Dearborn.

War of 1812

The War of 1812 could have been the War of Indian Independence. It was a major turning point for Native Americans who struggled to keep their lands and their culture.

The War formally began in June 1812 when President James Madison signed a Declaration of War against the United Kingdom. The underlying basis for the war included trade restrictions, the forcing of US merchant sailors into the service of the Royal Navy, the attempted annexation of Canada by the US, and British support of Native Americans in their fight against American expansion.

The war involved the British, the United States, in a minor way, Spain (in Florida), and Native Americans. Most Native American tribes sided with the British in an attempt to safeguard their tribal lands. They hoped a British victory would relieve the unrelenting pressure they were experiencing from US settlers. Settlers were pushing into Native-held territory in southern Canada, the lower Great Lakes and the south. Although some tribes remained neutral and some supported the United States, the majority allied with Britain. The Potawatomi allied themselves with the British, with some individual exceptions.

In Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, James W. Loewen says, “The American Indians were the only real losers in the war.”

After the War of 1812, the US negotiated more than 200 treaties with Native American nations that involved ceding land. 99 of those treaties resulted in the creation of reservations west of the Mississippi River.

In contrast, the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war in 1814 returned lands and agreements between the US and Britain to the way they were before the War. In exchange for the US leaving Canada alone, Britain stopped supporting Native Americans in their fight against the encroaching settlers.

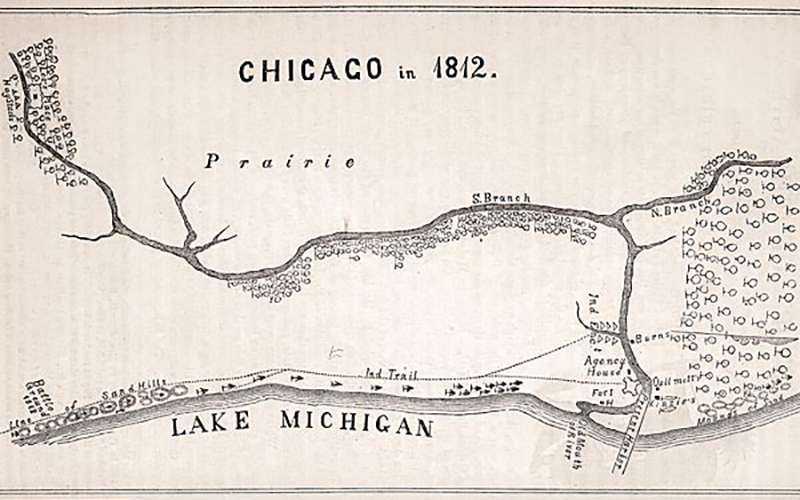

The Battle of Fort Dearborn

Before Chicago was platted, Fort Dearborn sat at the confluence of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan. A bloody battle took place here between the Potawatomi and US troops in August of 1812. The battle, which was a decisive victory for the Potawatomi, was once referred to as the Fort Dearborn Massacre. This was in keeping with the tradition that when Native Americans won, it was a massacre, but when the US Army massacred old men, women and children, it was a battle. The use of the term “massacre” also led to further genocide, the word itself inflaming settlers’ anger toward Native Americans, even though a war was underway at the time. The name has since been changed to the Battle of Fort Dearborn.

In 1810, while Prophetstown was growing, the combined Indian nations were planning their attacks against American posts. Main Poc, an influential chief, was to lead a force of Potawatomi against Fort Dearborn. Main Poc was injured during raids against the Osage, to the extent that he could not walk or ride. While he recovered and took on other tasks for the nations, he encouraged other Potawatomi chiefs – Blackbird and Mad Sturgeon – to raid the fort.

The land for the fort had been gained from the Treaty of Greenville. At the time it was in use, from 1804 to 1812, it was a key outpost in an undeveloped and remote area of the country. In Michigan, the US lost Fort Mackinac to the British and their Native allies without a shot being fired. Travel from Mackinac to Dearborn was quicker (across Lake Michigan) than overland travel to other forts. Now, the closest fort was 300 miles away. The US feared they would not be able to provide adequate supplies to Fort Dearborn.

Captain Nathan Heald at Fort Dearborn was ordered to evacuate, to destroy all ammunition and arms, and to distribute any remaining goods and provisions to friendly Native Americans in the area. The goods and provisions were to be payment for the Natives to provide an escort of the fort’s inhabitants to Fort Wayne. This message was sent by General William Hull and was delivered on August 9 by the Potawatomi leader “Winamek.” The order further said to leave immediately, before any Natives in the area heard of their plans.

General Hull sent word to Fort Wayne also, asking that they provide all assistance. Captain William Wells, an Indian agent at Fort Wayne, gathered men and supplies. Wells was the son-in-law of the Miami Chief Little Turtle and the uncle of Heald’s wife. He assembled a group of about 30 Miami, who remained neutral at this time, and traveled with them to Fort Dearborn to provide an escort. They arrived on August 12 or 13.

Captain Heald had already ignored the advice received from Chief Winamek. He not only didn’t leave immediately, but on August 14, he called a council meeting with the Potawatomi, informing them of his plans. According to the Potawatomi, Heald told them he would evacuate the fort and that he would distribute the firearms, ammunition and provisions among them. He further said that if they would send men to escort them safely to Fort Wayne, he would pay them a large sum of money upon arrival.

Instead, he destroyed the arms, ammunition and provisions.

On the morning of August 15, the garrison, comprised of 54 US regulars, 12 militia, nine women and 18 children, left the fort. Wells led the group with some of the Miami escorts while the rest of the Miami were at the rear. The wagons containing women and children were guarded by the militia.

A little more than a mile into the trip, 500 Potawatomi warriors under the direction of Blackbird and Mad Sturgeon, along with a few Kickapoo, Sac and Winnebago, took shelter behind dunes on Lake Michigan’s shore. Captain Wells saw the danger and led the regulars in a charge toward the war party. In the process, the cavalry was separated from the wagons. Both groups were surrounded.

In the end, Heald surrendered to the Potawatomi. Casualties included 26 regulars, all 12 of the militia, two women and twelve children killed, with the other 28 regulars, seven women, and six children taken prisoner. Captain Wells was among the dead.

Later, General William Henry Harrison, who was pursuing an aggressive campaign to take Native land, and who was not present at the battle, claimed the Miami had fought against the Americans. He used the Battle of Fort Dearborn as a pretext to attack Miami villages. Miami tribes accordingly ended their neutrality in the War of 1812 and allied with the British.

Seen from the perspective of the War of 1812, this was a very small and brief battle. Ultimately, it had larger consequences in the territory. Arguably, for Native Americans, it was an example of “winning the battle but losing the war.” The US later pursued a policy of removing the tribes from the region, resulting in the Treaty of Chicago in 1835. Thereafter, the Potawatomi and other tribes were moved further west.

Black Partridge

Potawatomi Chief Black Partridge was a friend to early American settlers. As the Potawatomi prepared for battle at Fort Dearborn, he advocated peace. On the evening of August 14, he rode ahead of the main force to warn Captain Heald of the coming battle.

The next day he and his brother Waubonsie tried to protect the departing residents of Fort Dearborn. Black Partridge saved the life of Mrs. Margaret Helm by holding her underwater under the appearance of drowning her in Lake Michigan. He later removed her to a nearby Indian camp where her wounds were dressed.

Later, Black Partridge also helped free her husband, Lt. Helm, who was being held captive by the Red Head Chief at Kankakee, delivering a ransom on behalf of US Indian Agent Thomas Forsyth. He voluntarily offered his pony, rifle, and a gold ring along with the original written order for $100 signed by General George Rodgers Clark.

Returning to his village on Peoria Lake, he found his village had been burned under orders from the Governor of Illinois, Ninian Edwards. Among the massacred included his daughter and his grandchild. Black Partridge renounced his allegiance with the US. (See Peoria War, below.)

Peoria War 1812

A nearly forgotten series of small skirmishes became known as the Peoria War.

The Native American population in Illinois had increased after 1811, when Tecumseh’s forces were defeated at Tippecanoe. In October 1812, Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards, using the US defeat at Fort Dearborn as a pretext, launched attacks against Kickapoo and Potawatomi villages in the Peoria area. A month later, another punitive attack came from Fort Knox in Kentucky. These incursions led indecisive Native Americans to fight with the British and Tecumseh’s ragtag confederacy of tribes.

About a year later, Tecumseh was killed in southern Ontario. A few weeks later, fewer than 200 Potawatomi and Kickapoo warriors led by Black Partridge were beaten back by more than 1,000 soldiers who had arrived from St. Louis. That winter, Black Partridge met in St. Louis with Missouri’s Territorial Governor William Clark, ending the Peoria War.

Black Hawk War 1832

In the 18th century, the Sauk and Fox tribes lived along the Mississippi River in what are now the states of Illinois and Iowa. The tribes had become closely connected after having been displaced from the Great Lakes region after the Fox Wars (1730s).

As the United States colonized westward in the early 19th century, government officials sought to buy as much Native American land as possible. In 1804, territorial governor William Henry Harrison negotiated a treaty in St. Louis in which a group of Sauk and Fox leaders supposedly sold their lands east of the Mississippi for $2,200 in goods and annual payments of $1,000 in goods.

The treaty became controversial because the Native leaders had not been authorized by their tribal councils to cede lands. Historians have concluded the chiefs probably did not intend to give up ownership of the land for so modest a price, or that they intended to cede a little land, but the Americans included more territory in the treaty’s language than the Natives realized.

The 1804 treaty allowed the tribes to continue using the ceded land until it was sold to American colonists by the US government. For the next two decades, they continued to live on their lands, including their main village of Saukenuk. In 1828, the US government finally began to have the ceded land surveyed for white colonies. Indian agent Thomas Forsyth informed the Sauk that they should vacate all settlements east of the Mississippi.

The Sauk tribe was divided about whether to resist implementation of the disputed 1804 treaty. Most decided to relocate west of the Mississippi rather than become involved in a confrontation with the United States. The leader of this group was Keokuk, who had helped defend the main Sauk village against the Americans during the War of 1812. Keokuk was not a chief, but as a skilled orator, he often spoke on behalf of the Sauk civil chiefs in negotiations with the Americans. Keokuk regarded the 1804 treaty as a fraud, but after having seen the size of American cities on the east coast in 1824, he did not think the Sauk could successfully oppose the United States.

Although the majority of the tribe decided to follow Keokuk’s lead, about 800 Sauk – roughly one-sixth of the tribe – chose instead to resist American expansion. Black Hawk, a war captain who had fought against the United States in the War of 1812 and was now in his 60s, emerged as the leader of this faction in 1829. Like Keokuk, Black Hawk was not a civil chief, but he became Keokuk’s primary rival for influence within the tribe.

Black Hawk had actually signed a treaty in May 1816 that affirmed the disputed 1804 land cession, but he insisted that what had been written down was different from what had been spoken at the treaty conference. According to Black Hawk, the “whites were in the habit of saying one thing to the Indians and putting another thing down on paper.”

Black Hawk was determined to hold onto Saukenuk, the main Sauk village where he lived and had been born. When the Sauk returned to the village in 1829 after their annual winter hunt in the west, they found that it had been occupied by white squatters who were anticipating the sale of land. After months of clashes with the squatters, the Sauk left in September 1829 for the next winter hunt. Hoping to avoid further confrontations, Keokuk told Forsyth that he and his followers would not return to Saukenuk.

Against the advice of Keokuk and Forsyth, Black Hawk’s faction returned to Saukenuk in the spring of 1830. This time, they were joined by more than 200 Kickapoo, a people who had often allied with the Sauks. When they returned again in 1831, the following had grown to about 1,500 and now included some Potawatomi.

Most Potawatomi wanted to remain neutral in the conflict but found it difficult to do so. Many white settlers, recalling the Battle of Fort Dearborn (at that time called the Fort Dearborn Massacre), distrusted the Potawatomi and assumed that they would join Black Hawk’s uprising. Potawatomi leaders worried that the tribe as a whole would be punished if any Potawatomi supported Black Hawk. At a council outside Chicago on May 1, 1832, Potawatomi leaders passed a resolution declaring any Potawatomi who supported Black Hawk a traitor to his tribe. In mid-May, Potawatomi chiefs Shabonna and Waubonsie told Black Hawk that neither they nor the British would come to his aid.

Without British supplies, adequate provisions, or Native allies, Black Hawk realized that his band was in serious trouble. By some accounts, he was ready to negotiate with Atkinson to end the crisis, but an ill-fated encounter with Illinois militiamen would end all possibility of a peaceful resolution.

From this point on, the situation became untenable. Through the US decision not to negotiate, miscommunications, false intelligence in just about every direction, misunderstandings due to language barriers, intertribal squabbles, the desire of militia members for blood-letting … Black Hawk’s rebellion became the Black Hawk War.

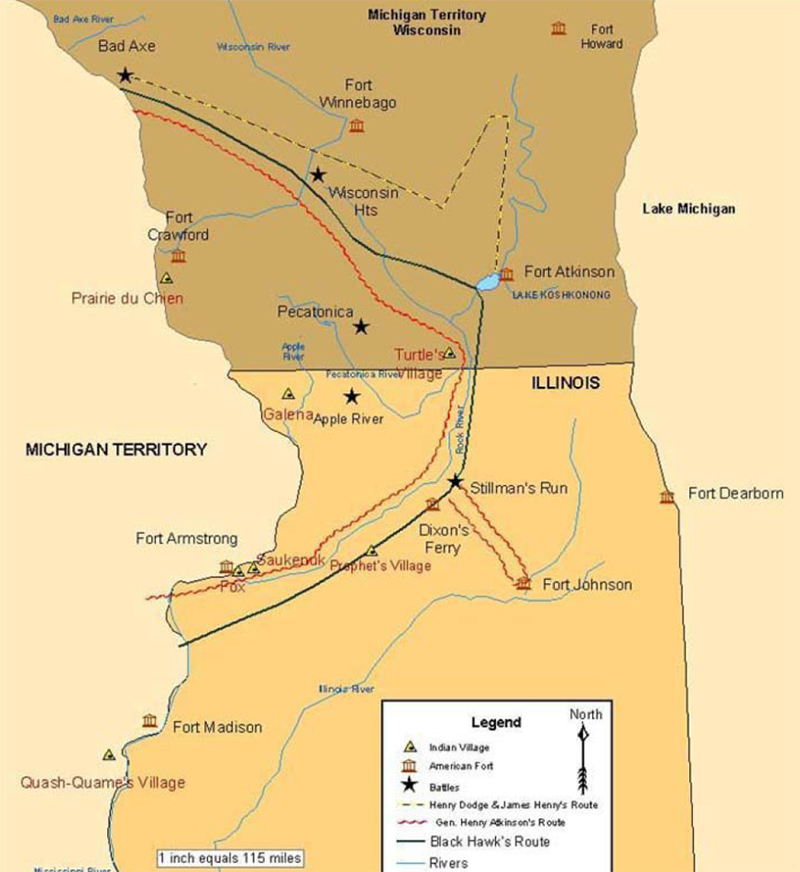

With hostilities now underway, and few allies to depend upon, Black Hawk sought a place of refuge for the women, children, and elderly in his band. Accepting an offer from the Rock River Ho-Chunks, the band traveled further upriver to the Michigan Territory and camped in an isolated place. Then, with a number of Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi allies, he began raiding white settlements. Potawatomi Chief Shabonna, on the other hand, rode throughout the settlements, warning whites of impending attacks.

The Black Hawk War resulted in the deaths of 77 white settlers, militiamen and regular soldiers. An estimated 450 – 600 Native Americans, or about half of the 1,100 who entered Illinois with Black Hawk in 1932, were lost. Black Hawk surrendered in August 1832.

The Black Hawk War marked the end of Native armed resistance to US expansion in the Old Northwest. The war provided an opportunity for American officials to compel Native American tribes to sell their lands east of the Mississippi River and move to the West, a policy known as Indian removal. Because Potawatomi leaders opted to aid the US during the war, officials did not seize tribal land as war reparations. Commissioners in Indiana bought a large amount of land, even though not all of the tribes were represented, and the tribe was compelled to sell their remaining land west of the Mississippi in the Chicago Treaty of 1833.

End to the Wars

The American-Indian Wars had effectively ended, but at great cost. Though Indians helped colonial settlers survive in the New World, helped Americans gain their independence, and ceded vast amounts of land and resources to pioneers, tens of thousands of Native American lives were lost to war, disease and famine, and the Indian way of life was almost completely destroyed.

The Series

-

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe