Overview of Potawatomi Involvement

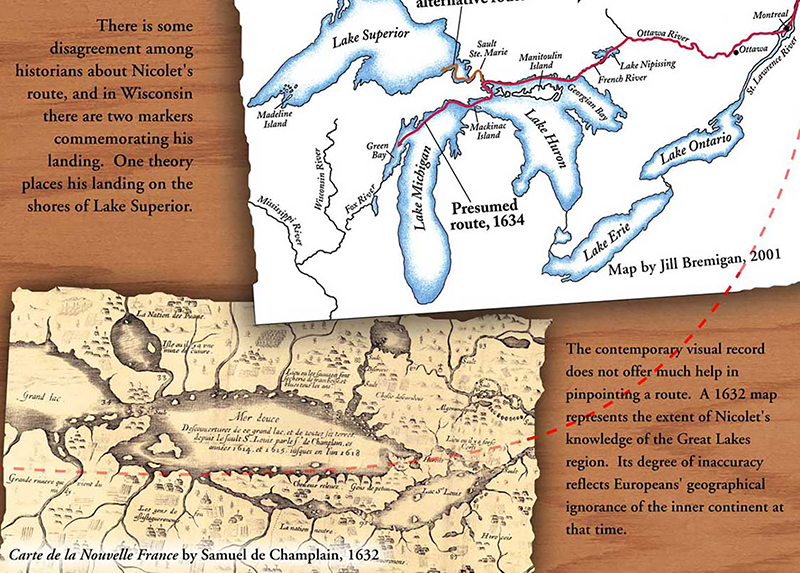

The first European contact with the Potawatomi occurred in 1634 when French explorer Jean Nicolet arrived at the area that would become Green Bay, Wisconsin. He landed there to trade and develop relationships with the Native Americans of the area, who happened to be the Menominee and Winnebago. On a side note, Nicolet believed he was closing in on the Pacific Ocean and a trade route to China. The Potawatomi entered recorded history at this time. Nicolet had the earliest recorded documents that mentioned members of this tribe.

The Potawatomi that met Nicolet were probably visiting or passing through, because they still lived in what would become Michigan. The Beaver Wars, perpetuated by the Five Nations of the Iroquois (starting in the 1640s) eventually pushed them west. By 1665, the tribe relocated on the Door County Peninsula in Wisconsin, close to what would become Green Bay.

Like other Great Lakes tribes, the Potawatomi became trading partners and military allies of the French. When the Fox Indians rose against the French in Wisconsin (between 1712 and 1735), the Potawatomi and other tribes took part in many battles on the side of the French. Beginning in 1731 and continuing into the 1740s, they aided the French in putting down the Chickasaw. Between 1752 and 1756, the Potawatomi again aided the French, this time against the Illinois tribe, who were eventually driven out of northern Illinois. The most important of the colonial wars was the French and Indian War, from 1754 to 1763. The Potawatomi continued to ally themselves with the French as did other tribes from Wisconsin and the Great Lakes region.

While the Potawatomi were not directly affected by wars that happened before that time, like all Native Americans, they were affected indirectly, negatively, and permanently by every colonial war. Because of that, we will touch on several.

Europeans Arrive in the Western Hemisphere

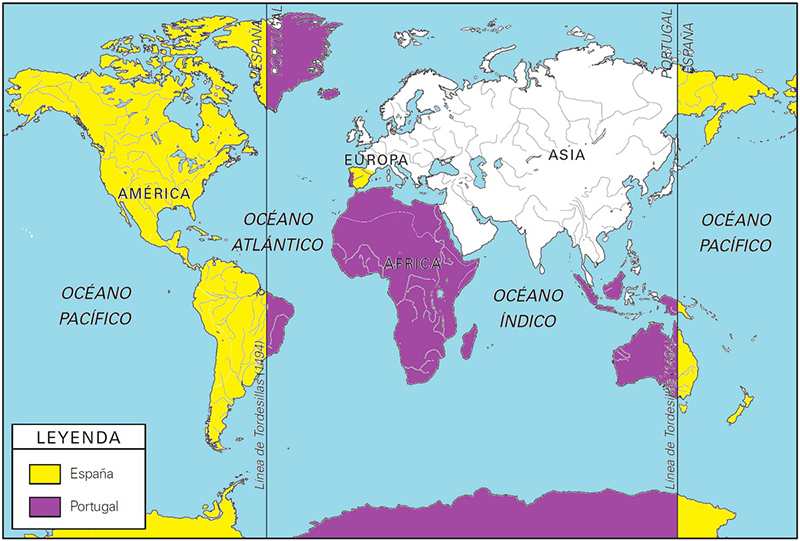

Upon the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, Portugal and Spain, with the blessing of the Pope, agreed to divide the Earth in two. Portugal was granted the non-Christian lands in the eastern half, and Spain those in the western half. Spain essentially claimed all the Americas, with the exception of the eastern tip of South America. That was given to Portugal and was established as Brazil. The city of St. Augustine, founded in 1565 in current-day Florida, is credited as the oldest continuously-inhabited European settlement in the contiguous United States.

By the 1530s, the British and French had begun colonizing the northeastern tip of the Americas. Within a century, Sweden had established New Sweden, the Dutch had established New Netherland, and Denmark-Norway made several claims in the Caribbean. By the 1700s, Denmark–Norway revived its former colonies in Greenland, and Russia had begun to explore and claim the Pacific Coast from Alaska to California.

Deadly confrontations became more frequent as Native Americans fought to preserve their land from increasing numbers of European colonizers. They also had to fight hostile native neighbors who were equipped with European technology.

Powhatan War: 1607-1618, 1622, 1644

The Powhatan Wars were three wars fought between settlers of the Virginia Colony and the Algonquin Indians of the Powhatan Confederacy. The final war resulted in a defined boundary between Native land and colonial lands that could only be crossed for official business with a special pass. This situation lasted until 1677, when another treaty established Indian reservations.

The Powhatan Confederacy was a group of about thirty tribes. Their native homeland was the area encompassing all of Tidewater, Virginia and parts of the Eastern Shore. Its boundaries spanned 100 miles from near the south side of the mouth of the James River, north to the south end of the Potomac River, and from the Eastern Shore west to about the Fall Line of the rivers.

They had little contact with Europeans until 1607. Upon arrival in Virginia, the English encountered terrible droughts and cold winters. Struggling to survive, they pressured the natives in the area for relief, which led to a series of conflicts along the James River. Eventually, the Confederacy perpetuated a siege of the English fort which lasted through the winter of 1609-10. The English survived, and, after the arrival of reinforcements, attacked using terror tactics. They burned villages and towns, executed women and children. After two years, Captain Samuel Argall captured the Indian Princess Pocahontas. He turned her into leverage to make peace. Not all historians see this first Anglo-Powhatan War as a distinct conflict, but from the Native American perspective, many argue it was the first English-Native American war. Eventually, a treaty was sealed by the marriage of Pocahontas to colonist John Rolfe. This was the first known inter-racial union in Virginia.

The second and third wars occurred as colonists continued to take native lands and natives continued to push back. Eventually, after many years of warfare, in October 1646, the General Assembly of Virginia signed a treaty bringing the Third Anglo-Powhatan War to an end. In the treaty, the tribes of the Confederacy became tributaries to the King of England, paying a yearly tribute to the Virginia governor. At the same time, a racial frontier was delineated between native and colonial settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by a special pass obtained at one of the border forts. The extent of the Virginia Colony open to settlers was defined as the land between the Blackwater and York rivers, and up to the navigable point of each of the major rivers. The treaty also permitted settlements on the peninsula north of the York and below the Poropotank, as they had already been there since 1640.

The tribes of the former confederacy were scattered, and the years saw the constant encroachment upon the lands designated to the natives in the treaty of 1646. The last Chief tried to work with the colonists, deeding them tribal lands, but his plan backfired. In 1662, colonists, wanting more, falsely accused the Chief of murder. Found innocent of all charges by a specially convened session of the House of Burgesses, he was nevertheless murdered by colonists while attempting to return home from his trial. Shortly thereafter the colonial government demanded all natives ‘sell’ their land, and in 1666 the government declared war, calling for the destruction of Natives. The tribes of the Northern Neck of Virginia were effectively wiped out; the few that managed to escape the settlers were absorbed into other remaining tribes in the region. The peace was shattered further by the attacks of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. This resulted in a treaty that set up reservations for each tribe.

Native Americans and the Mayflower: 1620

Stylized versions of the Pilgrims coming to America in 1620 suggest positive relationships between the Pilgrims and Native Americans. That idea, however, is largely false. The groups in southern New England generally lived in small, semipermanent villages where women tended fields of corn, beans, and squash. Men supplemented this diet by fishing and hunting. Women and children also gathered nuts and berries. In northern New England, where the climate was not conducive to farming, Native Americans depended on fishing, hunting, and gathering, as well as trade. When the agricultural land was depleted of nutrients, groups would move to settle nearby areas. As a result, they had a fundamentally different idea about the ownership of land than the Europeans.

Beginning in the 1600s, Native Americans began to trade with European merchants, exchanging beaver pelts for metals and textiles. Besides goods, Europeans also brought deadly diseases. Because the native peoples had no resistance to these diseases, illnesses had catastrophic effects. Experts estimate there were between 70,000 and 100,000 Native Americans living in New England at the beginning of the 17th century. A 1616 epidemic killed an estimated 75 percent of the Native Americans on the Atlantic Coast of New England. Historians believe the clearing where the Pilgrims settled was the site of a Pawtuxet village that had been wiped out by disease.

One Pawtuxet, Squanto, had been kidnapped by a European captain and taken to England. He freed himself and made his way home a few years later. Coming upon Squanto was fortunate for the Pilgrims. Squanto taught them how to plant corn and showed them where to fish and hunt. He also helped translate between English and Native American languages and to negotiate peace with local Native American chiefs.

But the Pilgrims, like all other European settlers, took for granted that what was theirs (the Natives) was now theirs (the Pilgrims).

Potawatomi: 1634, 1640s and 1650s

While the Powhatan Confederacy waged war in Virginia, the Potawatomi, at least a few of them, finally came into contact with French explorers. They were later pushed from their homeland by warring Iroquois in the Beaver Wars. SEE LINK FOR A BRIEF EXPLANATION

Pequot War: 1637-1638

The Pequot War took place in New England. It involved the Pequot tribe against an alliance of colonists from the Massachusetts Bay, the Plymouth and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes. The war concluded with a decisive defeat of the Pequot. At the end, about 700 Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity. Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to colonists in Bermuda or the West Indies. Other survivors were dispersed as captives to the victorious tribes. The result was the elimination of the Pequot tribe. Colonial authorities classified them as extinct. Survivors who remained were absorbed into other local tribes.

This war was the first instance in which Algonquian peoples of southern New England encountered European-style warfare. After the Pequot War, there were no significant battles between native tribes and southern New England colonists for about 38 years. This long period of peace came to an end in 1675 with King Philip’s War. The Pequot War introduced the practice of Colonists and natives taking body parts as trophies of battle. Honor and monetary reimbursement were given to those who brought back heads and scalps of Pequots.

NOTE: Europeans introduced this scalps-for-money plan.

King Philip’s War: 1675-1676

While Native Americans say the first Indian War was the first Powhatan conflict, King Philip’s War is called the first by European/white historians.

In 1675, the government of the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts executed three members of the Wampanoag people. The Wampanoag leader, Philip, retaliated by leading the Wampanoags and a group of other native peoples (including the Nipmuc, Pocumtuc, and Narragansett) against the settlement. Other peoples, including the Mohegans and Mohawks, fought the uprising with the English colonists. The war lasted 14 months, ending in late 1676. Much of the Native American opposition had been destroyed by the colonial militias and their Native American allies. Ultimately, a treaty was signed in April 1678, ending the conflict.

The war was the greatest calamity in seventeenth-century New England and is considered by many to be the deadliest war in Colonial American history. In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region’s towns were destroyed and many more were damaged, the economy of the Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined, and their populations were decimated. They lost one-tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Natives. Hundreds of Wampanoags and their allies were publicly executed or enslaved, and the Wampanoags were left effectively landless.

King Philip’s War began the development of an independent American identity. The New England colonists faced their enemies without support from any European government or military, and this began to give them a group identity separate and distinct from Britain. Centuries later, the New England colonies’ history shows the kind of duality that paints much of American history: the idea that native and immigrant cultures have come together to create the modern United States, coupled with the devastating conflicts and mistreatment that took place along the way.

King William’s War: 1689-1697: The First French & Indian War

King William’s War was largely caused by the fact that the treaties and agreements reached at the end of King Philip’s War were not adhered to. The English were alarmed that Native Americans were receiving French or maybe Dutch aid. The French thought the Natives were working with the English. These occurrences, plus the fact that the English perceived the Natives as their subjects, despite their unwillingness to submit, eventually led to two conflicts, one of which was King William’s War.

English traders had recently established the Hudson’s Bay Trading Company, which competed with French traders in Canada. Angry at British interference in the fur trade, the French incited the Abenaki tribes of Maine to destroy the rival English post of Pemaquid and attack frontier settlements. By this time, political divisions had fragmented the northern British colonies, each jealous of its own frontiers. These divisions interfered with relations between white settlers and American Indians and rendered British colonists susceptible to military assault.

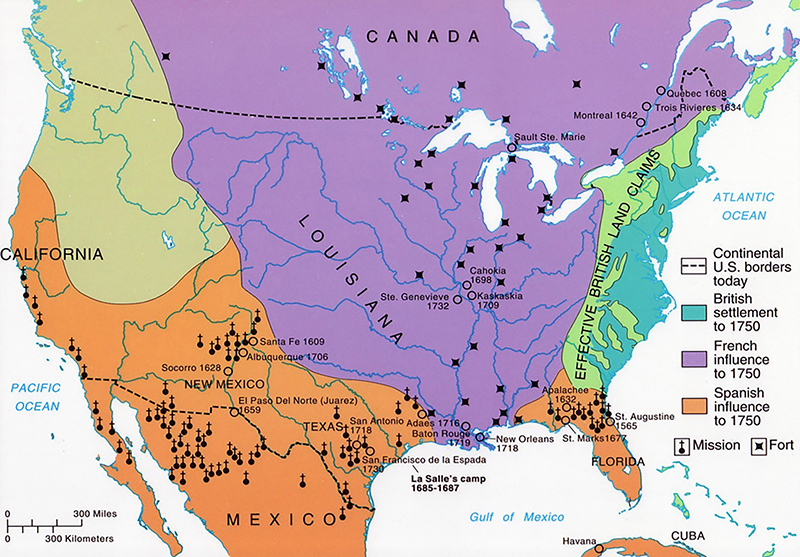

At the end of the 17th century, English settlers outnumbered the French 12 to 1, but the English were divided into multiple colonies along the Atlantic coast. They were unable to cooperate efficiently, and lacked military leadership. They also had a difficult relationship with their Iroquois allies. New France was divided into three entities: Acadia on the Atlantic coast, Canada along the Saint Lawrence River and up to the Great Lakes, and Louisiana from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, along the Mississippi River. They were more politically unified than the English and had a disproportionate number of adult males with military backgrounds. They had also developed good relationships with Native Americans in order to multiply their forces.

Although the French won this war, the treaty was inconclusive and did not result in significant transfers of North American land between European powers. The consequences for the Native Americans in the region, however, were severe. The war ignited a much longer struggle between the Algonquin and the Iroquois, which proved disastrous for both 562a14dxas they tried to negotiate with French and British colonists and officials. Because so many of the tensions that initially provoked the conflict remained unresolved, the North American frontier would again erupt in violence five years later, in Queen Anne’s War.

Queen Anne’s War: 1702-1713: The Second French & Indian War

Queen Anne’s War broke out in 1701 and was primarily a conflict among French, Spanish and English colonists over control of the North American continent, while, at the same time, the War of the Spanish Succession was being fought in Europe. Each side was allied with various Native American tribes. It was fought on four fronts:

- In the south, Spanish Florida and the English Province of Carolina attacked one another, and English colonists engaged French colonists based at Fort Louis de la Louisiane (near present-day Mobile, Alabama), with native tribes allied on each side. The southern war did not result in significant territorial changes, but it resulted in seriously decimating the Native American population of Spanish Florida and parts of southern Georgia and destroyed the network of Spanish missions in Florida.

- In New England, English colonists and native allies fought against French colonists and their native forces, especially in Acadia and unsettled border frontier with Canada. Quebec City was repeatedly targeted by British colonial expeditions, and the British captured the Acadian capital Port Royal in 1710.

- In Newfoundland, English colonists based at St. John’s disputed control of the island with the French colonists of Plaisance. Most of the conflict consisted of economically destructive raids on settlements.

- French privateers based in Acadia and Placentia captured many ships from New England’s fishing and shipping industries. Privateers took 102 prizes into Placentia, second only to Martinique in France’s American colonies. The naval conflict ended with the British capture of Acadia (Nova Scotia).

A treaty ended the war in 1713. France ceded the territories of Hudson Bay, Acadia, and Newfoundland to Britain while retaining Cape Breton Island and other islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Some terms were ambiguous in the treaty, and the concerns of various native tribes were not included, thereby setting the stage for future conflicts. The French did not fully comply with the commerce provisions of the treaty. They attempted to prevent English trade with remote Indian tribes, and they erected Fort Niagara in Iroquois territory. French settlements continued to grow on the Gulf Coast, with the settlement of New Orleans in 1718 and other (unsuccessful) attempts to expand into Spanish-controlled Texas and Florida. French trading networks penetrated the continent along the waterways feeding the Gulf of Mexico, renewing conflicts with both the British and the Spanish. Trading networks established in the Mississippi River watershed, including the Ohio River valley, also brought the French into more contact with British trading networks and colonial settlements that crossed the Appalachian Mountains. Conflicting claims over that territory eventually led to war in 1754.

Fox Wars: 1712 – 1737: The Potawatomi Enter The Colonial Wars: The First “Chief Winamac”

Led by prominent warriors Mackisabe, the elder Winemac and Madouche, the Potawatomi, along with allied France and other Great Lakes nations, enlisted to quell disruptive Fox attacks on the lucrative western fur trade and neighboring tribes. Angered that their Sioux enemies acquired weapons and supplies via the trade network, the Fox raided, killed and pillaged villages, merchants, and trade routes for two decades, implementing full-scale retaliation.

At the end of King William’s War, a trade issue was resolved by the establishment of a new fort, Fort Pontchartrain, at Detroit. The Fox controlled the Fox River system, vital for the fur trade between French Canada and the North American interior. It allowed for river travel from Green Bay on Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River. So, despite the fort’s strategic location, the French could not survive without the help of native populations.

The French Governor invited numerous tribes to settle in the area. Ottawa and Huron peoples established villages, soon joined by the Potawatomi, Miami and Ojibwa. The population may have reached 6,000 at times, positive for the French, but aggravating to the Fox. This erupted in the spring of 1712, leading to the first Fox War.

The two Fox Wars facilitated the entry of Fox slaves into colonial New France in two ways: as spoils of French military officers or through direct trading. Beginning with a treaty signed in 1716, slavery became an ongoing element of the Fox-French relationship. The French received scores of Fox slaves during the previous four years, placing themselves in a difficult diplomatic position between their allies and the Fox. By accepting these slaves, French colonists had symbolically acknowledged their enmity against the Fox, implicitly committing military support to their allies in future disputes.

Fox slavery in New France thus had a precarious symbolic power. On the one hand, the exchange of slaves signaled the possible end of conflict, while, on the other hand, it also served as a motive for inciting more conflict. In an early French manuscript describing the history of Green Bay, it is suggested that to gain peace with the Fox, it was more beneficial for opposing groups to simply return Fox captives than to take up arms against the Fox. Slaves were so commonly held that “every recorded complaint made by the Fox against the French and their native allies centered on the return of Fox captives, the most significant issue perpetuating the Fox Wars into subsequent decades.

Yet, long after the conflicts, Fox slaves worked in domestic service, unskilled labor and fieldwork, among other tasks throughout New France. Despite the abolishment of slavery in New France in accordance with a 1709 ordinance, Fox slavery was widespread. This pattern of slavery is evidence that intercultural experience in New France was sometimes vicious.

To summarize the slavery, after the First Fox War, roughly 1,000 Fox slaves were taken by the coalition of Native groups who were fighting the Fox. In addition, some were sold to the French in Detroit. In return, Native tribes received goods and credit. By the end of the Second Fox War, the practice of holding and selling the Fox into slavery led to the decline of French power in the Great Lakes Region.

Yamasee War: 1715-1717

The Yamasee War was fought in South Carolina between British settlers and a number of native groups. This war was one of the most disruptive and transformational conflicts of colonial America. About 7% of South Carolina’s settlers were killed, making the war one of the bloodiest wars in American history.

Embittered by settlers’ encroachment upon their land and by unresolved grievances arising from the fur trade, a group of Yamasees rose and killed 90 white traders and their families. All the surrounding Indian tribes except the Cherokee and the Lower Creek eventually allied themselves with Yamasee bands that continued to raid trading posts and plantations. South Carolinian military resistance was strengthened by additional troops from neighboring colonies and supplies from New England. Many of the defeated Indians escaped to Florida, joining runaway Black slaves and other Indians to form what later were called the Seminole.

King George’s War: 1744-1748: The Third French & Indian War

This war took place primarily in the British provinces of New York, Massachusetts Bay (which at the time included Maine), New Hampshire (which included Vermont), and Nova Scotia. At the end of the war, the peace treaty restored all colonial borders to their pre-war status and did little to end the lingering enmity between France, Britain, and their respective colonies. Nor did it resolve any territorial disputes. Tensions remained in both North America and Europe. They broke out again in 1754. Between 1749 and 1755 in Acadia and Nova Scotia, the fighting continued in Father Le Loutre’s War.

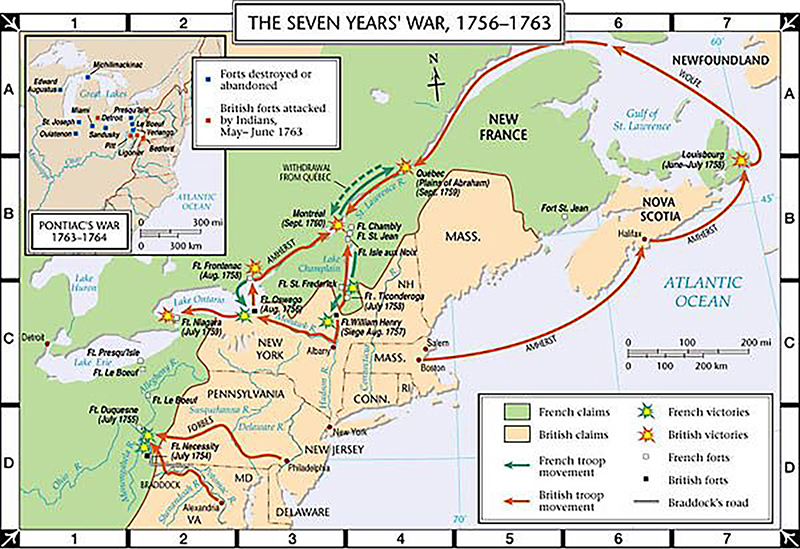

French & Indian War (Seven Years’ War) 1756-1763

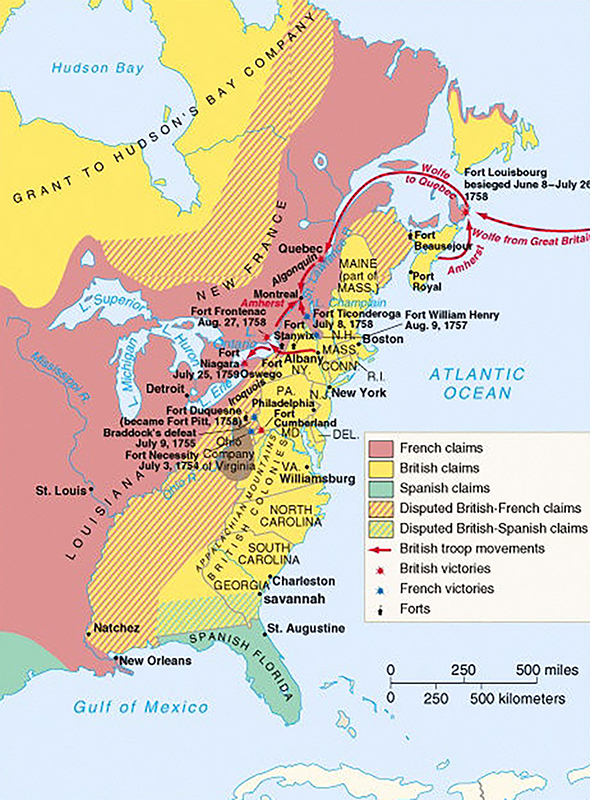

This war pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the start of the war, the French colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on the natives.

Two years into the French and Indian War, Great Britain declared war on France, beginning the worldwide Seven Years’ War. Many view the French and Indian War as being merely the American theater of this conflict; however, in the United States the French and Indian War is viewed as a singular conflict which was not associated with any European war.

The British colonists were supported at various times by the Iroquois, Catawba and Cherokee tribes, and the French colonists were supported by Wabanaki Confederacy member tribes Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, and the Algonquin, Lenape, Chippewa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Shawnee and Wyandot tribes. Fighting took place primarily along the frontiers between New France and the British colonies, from the Province of Virginia in the south to Newfoundland in the north.

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day New Brunswick and parts of Nova Scotia). Fewer lived in New Orleans, Biloxi, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama and small settlements in the Illinois Country. French fur traders and trappers traveled throughout the St. Lawrence and Mississippi watersheds, did business with local tribes, and often married native women. Traders married daughters of chiefs, creating high-ranking unions.

British settlers outnumbered the French 20 to 1, with a population of about 1.5 million ranged along the Atlantic coast of the continent from Nova Scotia and the Colony of Newfoundland in the north to the Province of Georgia in the south. Many of the older colonies’ land claims extended arbitrarily far to the west, as the extent of the continent was unknown at the time when their provincial charters were granted. Their population centers were along the coast, but the settlements were growing into the interior. The British captured Nova Scotia from France in 1713, which still had a significant French-speaking population. Britain also claimed Rupert’s Land, where the Hudson’s Bay Company traded for furs with local tribes.

Between the French and British colonists, large areas were dominated by Indian tribes. To the north, the Mi’kmaq and the Abenakis were engaged in Father Le Loutre’s War and still held sway in parts of Nova Scotia, Acadia, and the eastern portions of the province of Canada, as well as much of Maine. The Iroquois Confederation dominated much of upstate New York and the Ohio Country, although Ohio also included Algonquian-speaking populations of Delaware and Shawnee, as well as the Iroquoian-speaking Mingo. These tribes were formally under Iroquois rule and were limited by them in their authority to make agreements. The Iroquois Confederation initially held a stance of neutrality to ensure continued trade with both French and British. Maintaining this stance proved difficult, as the Iroquois Confederation tribes sided and supported French or British causes depending on which side provided the most beneficial trade.

The Southeast interior was dominated by Siouan-speaking Catawba, Muskogee-speaking Creek and Choctaw, and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee tribes. When war broke out, the French colonists used their trading connections to recruit fighters from tribes in western portions of the Great Lakes region, which was not directly subject to the conflict between the French and British; these included the Huron, Mississaugus, Ottawa, Winnebago, and Potawatomi.

The British colonists were supported in the war by the Iroquois Six Nations and also by the Cherokee, until differences sparked the Anglo-Cherokee War in 1758. In 1758, the Province of Pennsylvania successfully negotiated a treaty in which a number of tribes in the Ohio Country promised neutrality in exchange for land concessions and other considerations. Most of the other northern tribes sided with the French, their primary trading partner and supplier of arms. The Creek and Cherokee were subject to diplomatic efforts by both the French and British to gain either their support or neutrality in the conflict.

There were no French regular army troops stationed in America at the onset of war. New France was defended by about 3,000 companies of colonial regulars (some of whom had significant woodland combat experience). The colonial government recruited militia support when needed. The British had few troops. Most of the British colonies mustered local militia companies to deal with native threats, generally ill-trained and available only for short periods, but they did not have any standing forces. Virginia, by contrast, had a large frontier with several companies of British regulars.

When hostilities began, the British colonial governments preferred operating independently of one another and of the government in London. This situation complicated negotiations with native tribes, whose territories often encompassed land claimed by multiple colonies. As the war progressed, the leaders of the British Army establishment tried to impose constraints and demands on the colonial administrations.

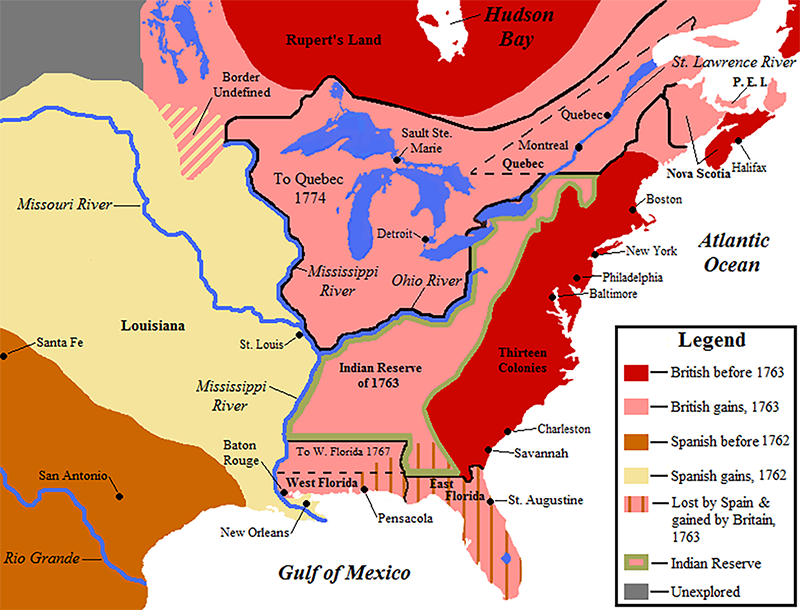

The war in North America, along with the global Seven Years War, officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in February, 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. The resulting peace dramatically changed the political landscape of North America, with New France ceded to the British and the Spanish. The war changed economic, political, governmental, and social relations among the three European powers, their colonies, and the people who inhabited those territories. France and Britain both suffered financially because of the war, with significant long-term consequences.

King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on October 7, 1763, which outlined the division and administration of the newly conquered territory, and it continues to govern relations to some extent between the government of Canada and the First Nations. Included in its provisions was the reservation of lands west of the Appalachian Mountains to its native population, a demarcation that was only a temporary impediment to a rising tide of westward-bound settlers.

The elimination of French power in America meant the disappearance of a strong ally for some Indian tribes. The Ohio Country was now more available to colonial settlement due to the construction of military roads. The Spanish takeover of the Louisiana territory was not completed until 1769, and it had modest repercussions. The British takeover of Spanish Florida resulted in the westward migration of Indian tribes who did not want to do business with them. This migration also caused a rise in tensions between the Choctaw and the Creek, historic enemies who were competing for land.

The French would return to support the fledgling United States in the American Revolutionary War.

The Series

-

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe