The Naming of Indiana

This LINK will take you to an article that appeared in the Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana Historical Society, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1903), pages 3-11, located in the Indiana State Library: The Naming of Indiana, by Cyrus W. Hodgin.

This LINK will take you to an article that appeared in the Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana Historical Society, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1903), pages 3-11, located in the Indiana State Library: The Naming of Indiana, by Cyrus W. Hodgin.

Wherein, you will learn this thing… that we used to be a part of Virginia.

Indiana Forms

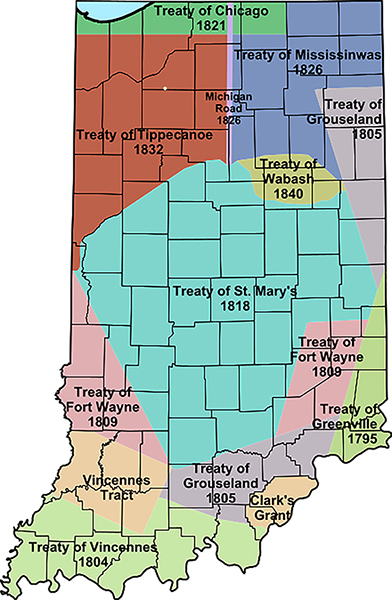

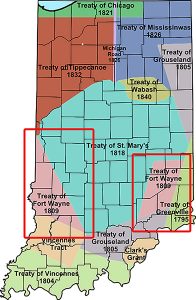

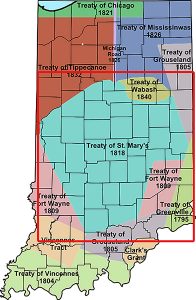

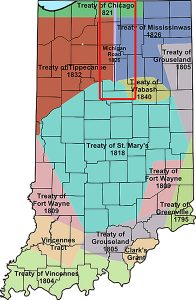

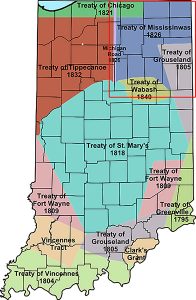

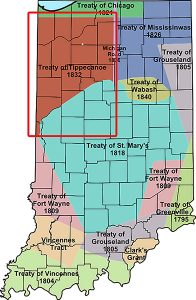

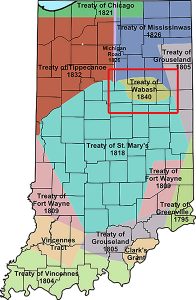

There were numerous treaties which directly affected the formation of the Indiana Territory and eventually the state itself. In each case, the treaties resulted in a major cession of Native American land, which slowly carved away the land of the long-time inhabitants of the region.

1781 Clark’s Grant

Clark’s Grant of 1783 was the first incursion into the Indiana Region.

The State of Virginia (see? a part of Virginia!) granted a tract of land to George Rogers Clark and the soldiers who fought with him during the American Revolutionary War. The tract was 150,000 acres and is located in present-day Clark County and parts of the surrounding counties.

Clark led the militia of Virginia in capturing a large part of the Illinois Country as part of the Illinois Campaign. Land was offered as an incentive to adventurers to sign up as soldiers and join the expedition. A commission of officers from the group was created and they were granted the right to choose any 150,000 acres within a defined region. They chose a tract across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, a settlement Clark founded during the war. Early settlements included Clarksville and Jeffersonville.

Clark led the militia of Virginia in capturing a large part of the Illinois Country as part of the Illinois Campaign. Land was offered as an incentive to adventurers to sign up as soldiers and join the expedition. A commission of officers from the group was created and they were granted the right to choose any 150,000 acres within a defined region. They chose a tract across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, a settlement Clark founded during the war. Early settlements included Clarksville and Jeffersonville.

Clark was still owed a vast sum of money for helping to finance the campaigns. These sums were never repaid to him during his life. Most of his land was taken by creditors, and he died nearly penniless, handicapped from injuries he sustained after the war. Virginia finally repaid most of his debt several years after his death.

Clark’s Grant contained the first American settlements in the modern state of Indiana. Clark himself received the largest tract, containing over 8,000 acres. Officers were granted large tracts; sergeants were given tracts of 216 acres; privates were given 108-acre tracts. There was some controversy, as privates were promised at least 300 acres.

1783 Vincennes Tract

(Captured from Great Britain during the Revolutionary War, US forged agreement with Miami, Wea & Shawnee)

(Captured from Great Britain during the Revolutionary War, US forged agreement with Miami, Wea & Shawnee)

The earliest land claims by inhabitants of Vincennes were based on a sale by the Indians to the French in 1742 of a tract of land containing 1.6 million acres, known as the Vincennes Tract. It was a rectangular block lying at right angles to the course of the Wabash River at Vincennes. The tract was ceded by France to Britain by treaty in 1763 after the French and Indian War. On October 18, 1775, an agent for the Wabash Company purchased two tracts of land along the Wabash River from the Piankeshaw tribe called the Plankashaw Deed. In these deeds, the Vincennes Tract was excepted, and it was the first recognition of the tract in period documents. Eventually, the United States Supreme Court invalidated the deeds.

The claims based on French sovereignty or individual deeds issued under it were eventually rejected by Congress, because if there were such grants, they passed to the United States by the Treaty of Paris 1783. By right of conquest, George Rogers Clark secured this land for the United States in 1779 and the Land Act of 1796 honored its boundaries.

1795 Treaty of Greenville

(Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Miami, Wea, Kickapoo & Kaskaskia)

(Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Miami, Wea, Kickapoo & Kaskaskia)

This little slice was originally part of Ohio Country.

The Treaty of Greenville was established between the United States and the Native nations of the Northwest Territory. This treaty redefined the boundary between Native lands and territory for European American settlements. It was signed at Fort Greenville, now Greenville, Ohio, following the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers a year earlier.

It ended the Northwest Indian War in the Ohio Country, limited Indian Country to northwestern Ohio, and began the practice of annual payments following land concessions. The treaty became synonymous with the end of the frontier in that part of the Northwest Territory that would become the new state of Ohio.

During the signing of the treaty, Native Americans were informed that the US Senate had ratified the Jay Treaty, ensuring that Great Britain would no longer provide aid to Native Americans. They were also warned that if they did not negotiate this treaty, General Anthony Wayne had the military power to take all of their lands.

1803 Treaty of Fort Wayne

(Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Miami, Eel River Miami, Kickapoo, Wea, Piankashaws & Kaskaskias)

This treaty more precisely defined the boundaries of the Vincennes tract ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Greenville, 1795.

1804 Treaty of Vincennes

(Had the effect of connecting Clark’s Grant & the Vincennes Tract, allowing white settlers to freely settle)

(Had the effect of connecting Clark’s Grant & the Vincennes Tract, allowing white settlers to freely settle)

The Treaty of Vincennes is the name of two separate treaties. One was an agreement between the US and the Miami and their allies, the Wea tribes and the Shawnee. The purpose of the treaty was to get the native tribes to formally recognize the American ownership of the Vincennes Tract, a parcel of land captured from Great Britain during the Revolutionary War.

The second treaty was to purchase land from the tribes. The area purchased was south of the Vincennes tract and the Buffalo Trace, north of the Ohio River and east of the Wabash River. The treaty had the effect of connecting Clark’s Grant and the Vincennes Tract. The area had many squatters living on native owned lands which led to rising tensions with the tribes; the treaty relieved pressure on the settlers, allowing them to freely settle the land.

1805 Treaty of Grouseland

(Miami, Lenape)

(Miami, Lenape)

This treaty was between the US, negotiated by Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison with Little Turtle (Miami) and Buckongahelas (Lenape). It was negotiated and signed at Harrison’s home in Vincennes, called Grouseland. It was the second major land purchase in Indiana since the close of the Northwest Indian War and the signing of the Treaty of Greenville.

The Miami Tribe had the principle claim to the land that was purchased, but many other tribes inhabited the area. Many settlers were moving into the area, the result being rising tensions with the tribes, who considered the settlers to be trespassers. Shortly after the approval of the treaty, numerous settlements sprung up in the opened land, including Madison.

1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne

(Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami & Eel River Miami)

(Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami & Eel River Miami)

This treaty is sometimes called the Ten O’clock Line Treaty or the Twelve Mile Line Treaty. It obtained 29,719,530 acres of Native American land for the settlers of Illinois and Indiana. The negotiations included the Delaware tribe primarily, as well as other tribes. It excluded the Shawnee, who were minor inhabitants of the area. The treat led to a war with the US begun by Shawnee leader Tecumseh.

The first nickname comes from tradition that says the Native Americans did not trust the surveyors’ equipment, so a spear was thrown down at ten o’clock. The shadow became the treaty line. The Twelve Mile Line was a reference to the Greenville Treaty and the establishment of a new ‘line’ parallel to it but twelve miles further west.

In 1809 Harrison began to push for a treaty to open more land for white American settlement. The Miami, Wea, and Kickapoo were “vehemently” opposed to selling any more land around the Wabash River. To motivate those groups to sell their land, Harrison decided, against the wishes of President James Madison, to first conclude a treaty with the tribes who were willing to sell and use those treaties to help influence those who held out. In September 1809, Harrison invited the Potawatomie, Delaware, Eel Rivers, and the Miami to a meeting in Fort Wayne. During the negotiations, Harrison promised large subsidies and direct payments to the tribes if they would cede the other lands under discussion.

Only the Miami opposed the treaty. They presented a copy of the Treaty of Greenville to highlight the section that guaranteed their possession of the lands around the Wabash River. They then explained the history of the region and how they had invited the Wea and other tribes to settle in their territory as friends. The Miami were concerned that the Wea leaders were not present at the negotiations even though they were the primary inhabitants of the land being sold. The Miami also wanted any new land sales to be paid for by the acre, and not by the tract. Harrison agreed to make the treaty’s acceptance contingent on approval by the Wea and other tribes in the territory being purchased, but he refused to purchase land by the acre. He countered that it was better for the tribes to sell the land in tracts so as to prevent the Americans from only purchasing their best lands by the acre and leaving the tribes with only poor land on which to live.

After two weeks of negotiating, the Potawatomie leaders convinced the Miami to accept the treaty as reciprocity to the Potawatomie who had earlier accepted treaties less advantageous to their tribe at the request of the Miami. The Treaty of Fort Wayne was finally signed on September 29, 1809, selling the United States over 3,000,000 acres, mostly along the Wabash River north of Vincennes.

Tecumseh was the powerful leader of a breakaway Shawnee group living just north of the area covered in the treaty. He questioned the legality of the treaty stating that these Native leaders did not have the right to sign the treaty, and rightfully sell land that is held in common with other Native peoples. In August 1810, he led 400 armed warriors from several different tribes in traveling down the Wabash to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate and asked Harrison to nullify it, ominously warning that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh acknowledged to Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms. Harrison responded to Tecumseh that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so choose. In a move that further impacted American relations with the Indians, Harrison also rejected Tecumseh’s claim that all the Indians formed one nation and that each nation could have separate negotiations with the United States.

Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the treaty was nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British. The situation continued to escalate, eventually leading to the outbreak of hostilities between Tecumseh’s followers and American settlers later that year. Tensions continued to rise, leading to the Battle of Tippecanoe during a period called Tecumseh’s War.

1818 Treaty of St. Mary’s

(Wyandot, Potawatomi, Wea, Delaware & Miami)

(Wyandot, Potawatomi, Wea, Delaware & Miami)

The Treaty of St. Mary’s may refer to one of six treaties concluded in fall of 1818 between the United States and Natives of central Indiana regarding purchase of Native land. The treaties were:

- Treaty with the Wyandot and others

- Treaty with the Wyandot

- Treaty with the Potawatomi

- Treaty with the Wea

- Treaty with the Delaware

- Treaty with the Miami

The main treaty was with the Miami, who were the main tribe in Indiana. Unqualified references to the treaty usually refer to this one. The treaties acquired a substantial portion of the land area (dubbed the New Purchase) of the state of Indiana from the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi and others in exchange for cash, salt, sawmills, and other goods. The treaties effectively moved the northern boundary of the state from near the Ohio River to the Wabash River in the northwest and north. They also resulted in creation of Indian reservations and continued the process of Indian removals in Indiana begun by the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

The first reservation was established, the Great Miami Reserve in the northern portion of the New Purchase. In addition to a perpetual annuity, the US agreed to construct one gristmill and one sawmill and to provide one blacksmith, one gunsmith, agricultural implements, and annual allotments of salt.

The Miami were now confined to the reserve area; the Delaware were removed to west of the Mississippi. 35 new counties were carved out of the original area for settlement, including the area where the future state capital, Indianapolis, would be founded in 1822.

1821 Treaty of Chicago

(Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi: the Council of Three Fires)

(Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi: the Council of Three Fires)

In 1795, a then-minor part of the Treaty of Greenville granted rights to the US in a six-mile parcel of land at the mouth of the Chicago River. This was followed in 1816 by the Treaty of St. Louis, which ceded additional land in the Chicago area, including the Chicago Portage.

The first Treaty of Chicago (1821) was signed by Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass and Solomon Sibley for the US, and representatives of the Council of Three Fires: Ottawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi. The treaty ceded to the US all lands in Michigan Territory south of the Grand River, with the exception of several small reservations. Also ceded was a tract of land, easement between Detroit and Chicago (through Indiana and Illinois) around the southern coast of Lake Michigan. Specific Native Americans were granted property rights to defined parcels.

Potawatomi chief Metea gave the following speech in defense of his land at the signing of the treaty.

My Father, we have listened to what you have said. We shall now retire to our camps and consult upon it. You will hear nothing more from us at present. [This was a uniform custom. When the council was again convened, Metea continued.]

We meet you here today, because we had promised it, to tell you our minds, and what we have agreed upon among ourselves. You will listen to us with a good mind, and believe what we say. You know that we first came to this country, a long time ago, and when we sat ourselves down upon it, we met with a great many hardships and difficulties. Our country was then very large; but it has dwindled away to a small spot, and you wish to purchase that! This has caused us to reflect much upon what you have told us; and we have, therefore, brought all the chiefs and warriors, and the young men and women and children of our tribe, that one part may not do what others object to, and that all may be witnesses of what is going forward. You know your children. Since you first came among them, they have listened to your words with an attentive ear, and have always hearkened to your counsels. Whenever you have had a proposal to make to us, whenever you have had a favor to ask of us, we have always lent a favorable ear, and our invariable answer has been ‘yes.’ This you know! A long time has passed since we first came upon our lands, and our old people have all sunk into their graves. They had sense. We are all young and foolish, and do not wish to do anything that they would not approve, were they living. We are fearful we shall offend their spirits, if we sell our lands; and we are fearful we shall offend you, if we do not sell them. This has caused us great perplexity of thought, because we have counselled among ourselves, and do not know how we can part with the land. Our country was given to us by the Great Spirit, who gave it to us to hunt upon, to make our cornfields upon, to live upon, and to make down our beds upon when we die. And he would never forgive us, should we bargain it away. When you first spoke to us for lands at St. Mary’s, we said we had a little, and agreed to sell you a piece of it; but we told you we could spare no more. Now you ask us again. You are never satisfied! We have sold you a great tract of land already; but it is not enough! We sold it to you for the benefit of your children, to farm and to live upon. We have now but little left. We shall want it all for ourselves. We know not how long we may live, and we wish to have some lands for our children to hunt upon. You are gradually taking away our hunting-grounds. Your children are driving us before them. We are growing uneasy. What lands you have, you may retain forever; but we shall sell no more. You think, perhaps, that I speak in passion; but my heart is good towards you. I speak like one of your own children. I am an Indian, a red-skin, and live by hunting and fishing, but my country is already too small; and I do not know how to bring up my children, if I give it all away. We sold you a fine tract of land at St. Mary’s. We said to you then, it was enough to satisfy your children, and the last we should sell: and we thought it would be the last you would ask for. We have now told you what we had to say. It is what was determined on, in a council among ourselves; and what I have spoken, is the voice of my nation. On this account, all our people have come here to listen to me; but do not think we have a bad opinion of you. Where should we get a bad opinion of you? We speak to you with a good heart, and the feelings of a friend. You are acquainted with this piece of land—the country we live in. Shall we give it up? Take notice, it is a small piece of land, and if we give it away, what will become of us? The Great Spirit, who has provided it for our use, allows us to keep it, to bring up our young men and support our families. We should incur his anger, if we bartered it away. If we had more land, you should get more; but our land has been wasting away ever since the white people became our neighbors, and we have now hardly enough left to cover the bones of our tribe. You are in the midst of your red children. What is due to us in money, we wish, and will receive at this place; and we want nothing more. We all shake hands with you. Behold our warriors, our women, and children. Take pity on us and on our words.

1826 Michigan Road

(Potawatomi)

(Potawatomi)

The Michigan Road was one of the earliest roads in Indiana. Roads in early Indiana were often roads in name only. In actuality, they were sometimes little more than crude paths following old animal and Native American trails and filled with sinkholes, stumps, and deep, entrapping ruts. Hoosier leaders, however, recognized the importance of roads to the growth and economic health of the state, and the needed improvements. They encouraged construction of roads which would do for Indiana what the National Road was doing for the whole country.

Indiana’s first “super highway” was the Michigan Road, which was built in the 1830s and 1840s and ran from Madison to Michigan City via Indianapolis. Like the National Road, it did much to spur settlement and economic growth. Half of the pioneers to settle northwestern Indiana did so by using the Michigan Road to travel from the Ohio River to their destination. It was the “most ambitious” project to connect Indianapolis with the rest of the state.

One of the things that made the road possible was a treaty the state of Indiana forged with the Potawatomi on October 16, 1826. It allowed for a ribbon of land 100 feet wide to stretch from the Ohio River at Madison to Lake Michigan in Michigan City. The Pottawatomie left the region by that very road when the last of their tribe was forcibly removed in the 1838 Trail of Death.

1826 Treaty of Mississinwas

(Miami & Potawatomi)

(Miami & Potawatomi)

This was also called the Treaty of the Wabash and was made with the Miami and Potawatomi Tribes. The signing was held at the mouth of the Mississinewa River on the Wabash and regarded the purchase of lands in Indiana and Michigan.

The Miami agreed to cede to the US the bulk of Miami reservation lands held in Indiana by previous treaties. In compensation, the families of Chief Richardville and other Miami notables were given estates in Indiana, with houses and livestock furnished at government expense. Small reservations were to be carved out along the Eel and Maumee rivers. Silver was also to be paid the first year, goods the next, and promises were made of an annuity thereafter.

Adhering to the terms was difficult for both sides. White treaty makers did not necessarily understand the complexities and fluidity of Indian tribal societies, and often overestimated the nature of the authority vested in a particular chief by the band, the permanence of tribal membership and intertribal alliances, and the permanence of Indian settlements, which often shifted according to the season. Younger males were more likely than their elders to prefer the use of force against white settlers to negotiations. Mixed-race native and Canadian tribal members were more likely to support the treaty and its implementation, as they benefited more from land grants and subsidies than other tribespeople. Disagreements about the applicability of treaty terms made it more difficult to create the Michigan Road on lands that were supposed to have been ceded by the treaty.

1832 Treaty of Tippecanoe

(Potawatomi)

(Potawatomi)

The Treaty of Tippecanoe was an agreement between the US government and Potawatomi tribes. The US had already purchased the Miami claim to the region in a previous treaty. The Potawatomi were the only natives who still held a claim in the region. The land purchased was most of the northwestern part of the state of Indiana. It was recorded in the treaty as:

beginning at a point on Lake Michigan, where the line dividing the States of Indiana and Illinois intersects the saline thence with the margin of said Lake, to the intersection of the southern boundary of a cession made by the Potawatomi, at the treaty of the Wabash, of eighteen hundred and twenty-six; thence east, to the northwest corner of the cession made by the treaty of St. Joseph’s, in eighteen hundred and twenty-eight; thence south ten miles; thence with the Indian boundary line to the Michigan road; thence south with said road to the northern boundary line, air designated in the treaty of eighteen hundred and twenty-six, with the Potawatomi; thence west with the Indian boundary line to the river Tippecanoe; thence with the Indian boundary line, as established by the treaty of eighteen hundred and eighteen, at St. Mary’s to the line dividing the States of Indiana and Illinois; and thence north, with the line dividing the said States, to the place of beginning.

The treaty provided for establishing a reserve for the Pottawatomie along the Yellow River, and to build a mill for them on that reservation. In exchange for the land, the Potawatomi tribe was granted an annual payment of $20,000 for a term of twenty years. Upon signing the treaty, the tribe was also granted $100,000 in goods, and a lump sum payment of $62,412 for payment of debts owed by the Potawatomi. The government also offered the tribes assistance in moving to new lands in Indian Territory, and providing farming implements to assist them in cultivating the land they would move to.

The native tribes agreed, and the following tribal leaders signed the treaty with an X mark: Louison, Che-ehaw-eose, Banack, Man-o-quett, Kin-kosh, Pee-shee-Nvaw-no, Menominee, Mis-sah-kaw-way, Kee-waw-nay, Sen-bo-go, Che-quaw-ma-eaw-co, Muak-kose, Ah-you-way, Po-kah-kause, So-po tie, Newark, Che-man, No-taw-kah, Nas-waw-kee, Pec-pin-a-paw, Ma-ehe-saw, O-kitch-ehee, Pee-pish-kah, Conl-mo-yo, Chiek-kose, Mis-qua buck, Mo-tie-ah, Muck-ka-tah-mo-tvay, Mah-qusw-shee, O-sheh-weh, Mah-zick, Queh-kah-pah, Quash-quaw, Louisor Perish, Pam-bo-go, Bee-ya w-yo, Pah-ciss, Mauck-eo-pavv-waw, Mis-sah-qua, Kawk, Miee-kiss, Shaw-bo, Aub-be-naub-bee, Mau-maut-wah, O-ka-mause, Pash-ee-po, We-wiss-lai, Ash-kom, and Waw-zee-o-nes.

1836 Treaty of Yellow River

(Potawatomi)

The Treaty of Yellow River, one of Indiana’s more contentious treaties, offered the Potawatomi $14,080 for two sections of Indiana land, but Chief Menominee and seventeen others refused to accept the terms of the sale. The Yellow River band of Potawatomi living near Twin Lakes, Indiana, led by Chief Menominee, refused to take part in the negotiations and did not recognize the treaty’s authority over their band.

Under the terms of treaties made in 1836, the Potawatomi were required to vacate their land in Indiana within two years, including the Yellow River band. Menominee refused: “I have not signed any treaty, and will not sign any. I am not going to leave my land, and I do not want to hear anything more about it.” Father Deseille, the Catholic missionary at Twin Lakes, also denounced the Yellow River Treaty as a fraud. Col. Pepper, the federal government’s treaty negotiator, believed that Father Deseille was interfering with their plans for removal of the Potawatomi from Indiana, and ordered the priest to leave the mission at Twin Lakes or risk prosecution. The federal government refused Menominee’s demands, and the chief and his band were forced to leave the state in 1838.

Indiana governor David Wallace authorized General John Tipton to forcefully remove the Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death, the single largest Indian removal in the state. Beginning on September 4, 1838, a group of 859 Potawatomi were force marched from Twin Lakes to Osawatomie, Kansas. The difficult journey of about 660 miles in hot, dry weather and without sufficient food or water, lead to the death of 42 people, 28 of them children.

Subsequent treaties with other Potawatomi tribes ceded additional lands in Indiana and removals continued. In a treaty made on September 23, 1836, the federal government agreed to purchase forty-two sections of their Indiana land for $33,600 (or $1.25 per acre, the minimum purchase price the government could receive from the sale of public lands). A treaty made with the Potawatomi on February 11, 1837, provided for further cessions of Indiana land in exchange for a parcel of reservation land for tribal members on the Osage River, southwest of the Missouri River in present-day Kansas, and other guarantees. Another small group of Potawatomi from Indiana removed in 1850. Those who had been forcefully removed were initially relocated to reservation land in eastern Kansas but moved to another reservation in the Kansas River valley after 1846. Not all the Potawatomi from Indiana removed to Kansas. A small group joined an estimated 2,500 Potawatomi in Canada.

1840 Treaty of the Wabash

(Miami)

(Miami)

The Treaty of the Wabash was an agreement between the United States government and Native American Miami tribes.

The US had already purchased the Miami claim to the region, and the Potawatomi were the only natives who still held a claim in the region. The land purchased was in the region of the headwaters of the Wabash in north central Indiana and constituted no more than about 500,000 acres. The tribe agreed to accept designated lands in the Indian Territory, present day Oklahoma, as a final place of settlement.

The Series

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe