Who would think that the story of a mastodon discovered in Pulaski County would begin with drainage issues? This is the story of the recovery of the mastodon skeleton from a marsh bog, in Judge Reidelbach’s words.

A Century of Achievement, Pulaski County, Indiana 1839 – 1939

By John G. Reidelbach, Edited and Published by Richard R. Dodd, 1972, Indexed by Iona Harshberger Nale & Julia Phillips Fagan

By John G. Reidelbach, Edited and Published by Richard R. Dodd, 1972, Indexed by Iona Harshberger Nale & Julia Phillips Fagan

The following information comes from a book that was researched and written by Judge John G. Reidelbach. The book remained unfinished and unpublished at his death in 1939. Portions of the book were printed in local newspapers over the years. Eventually, after several years as a “project” of local historian and former County Clerk, Richard Dodd, the book was published for limited distribution. What follows is verbatim from Mr. Dodd’s publication.

Pulaski County Marshlands

The greater portion of the land area of Pulaski County was swamp lands and entered as such by original purchasers. Before drainages were constructed these lands were very wet and unhealthy, producing practically nothing but wild hay. The earlier settlers suffered much sickness from malaria and ague, many dying as a result.

After the wet lands were drained, healthier conditions prevailed, and untiring pioneers prospered, improved their homes, and made great advancements in agricultural pursuits on their farms until the farm lands in the county are second to none for raising corn, wheat, oats, clover, and all other kinds of food and vegetables.

The Blue Sea

As the Big Monon ditch crosses the county line between Starke and Pulaski Counties, continuing into Pulaski County through section six of Rich Grove Township for about a mile, it passes through a large area of some four or five sections of low, swampy lands known as the Blue Sea marsh. In earlier days this marsh was a lake and as the water level was lowered in that locality it left a large area of swampy lands and is still known as the Blue Sea.

The construction and reconstruction of the Monon ditch made valuable agricultural lands of the greater portion of the swamp lands. Contractors who constructed drainage tributaries to the Monon in the Blue Sea, and farmers who proceeded to cultivate the lands for agricultural purposes have frequently unearthed relics of the prehistoric age.

The construction and reconstruction of the Monon ditch made valuable agricultural lands of the greater portion of the swamp lands. Contractors who constructed drainage tributaries to the Monon in the Blue Sea, and farmers who proceeded to cultivate the lands for agricultural purposes have frequently unearthed relics of the prehistoric age.

A Mastodon Found

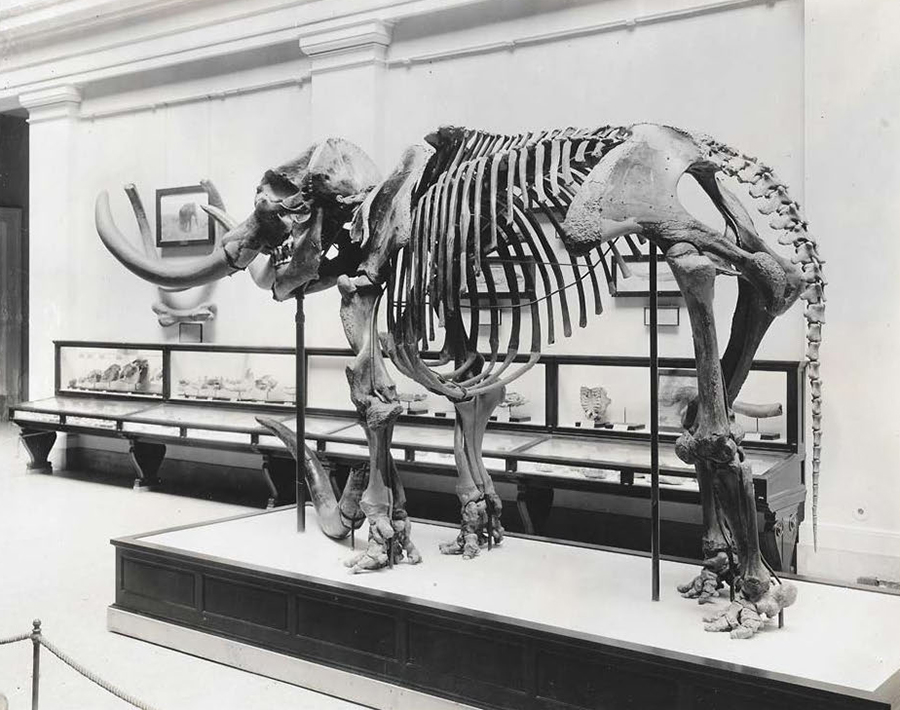

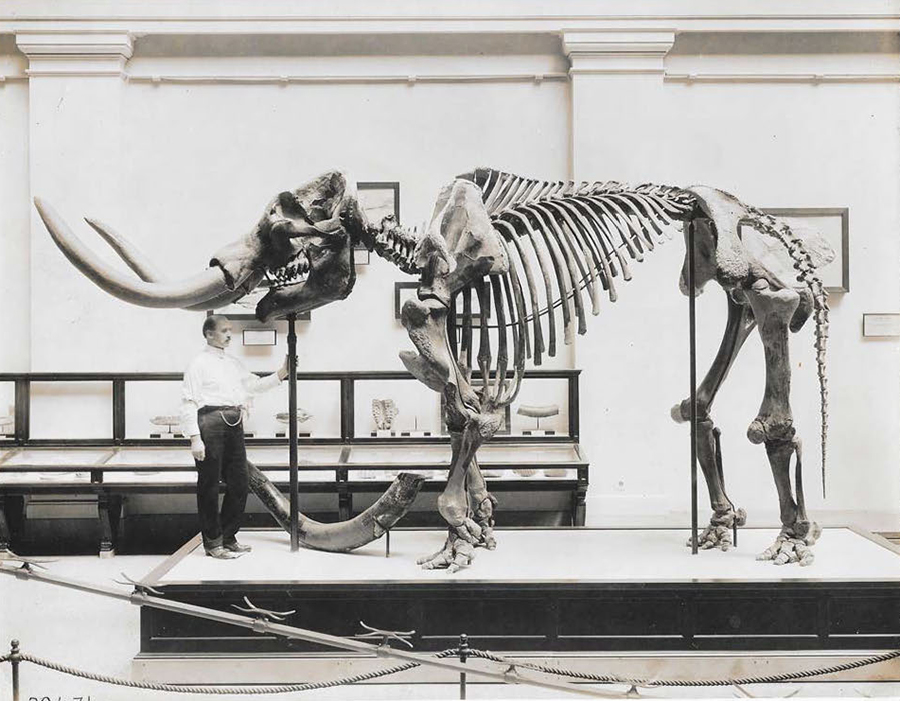

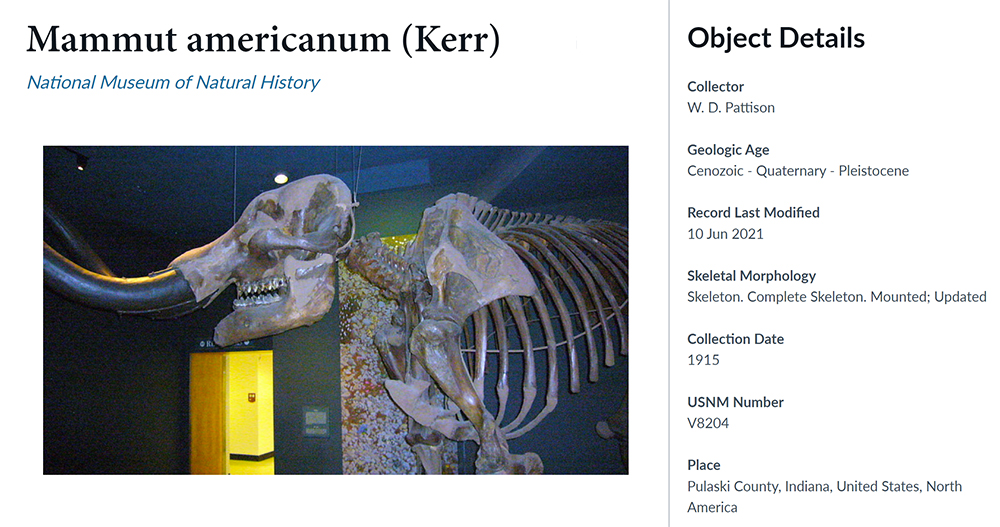

A visitor to the National Museum at Washington, D.C. [now known as the Smithsonian] will find there standing on a platform assembled and mounted a large skeleton of a mastodon, an extinct genus of mammals and species of the elephant family. This skeleton is the remains of a prehistoric animal which lived several thousand years ago and is the largest of its kind known in American history. While gazing at this structure one wonders of what country and climate the living animal was an inhabitant.

Upon reading the description encased in a small frame setting on the platform in front of the skeleton the viewer will be surprisingly informed that the remains of this massive animal were excavated by a dredge contractor (Frank M. Williams of Winamac) while constructing the William D. Pattison branch ditch in the large Monon ditch, in what is known as the Blue Sea marsh of Rich Grove Township, in the summer of 1914.

Upon reading the description encased in a small frame setting on the platform in front of the skeleton the viewer will be surprisingly informed that the remains of this massive animal were excavated by a dredge contractor (Frank M. Williams of Winamac) while constructing the William D. Pattison branch ditch in the large Monon ditch, in what is known as the Blue Sea marsh of Rich Grove Township, in the summer of 1914.

The inscription relating to the mastodon skeleton follows.

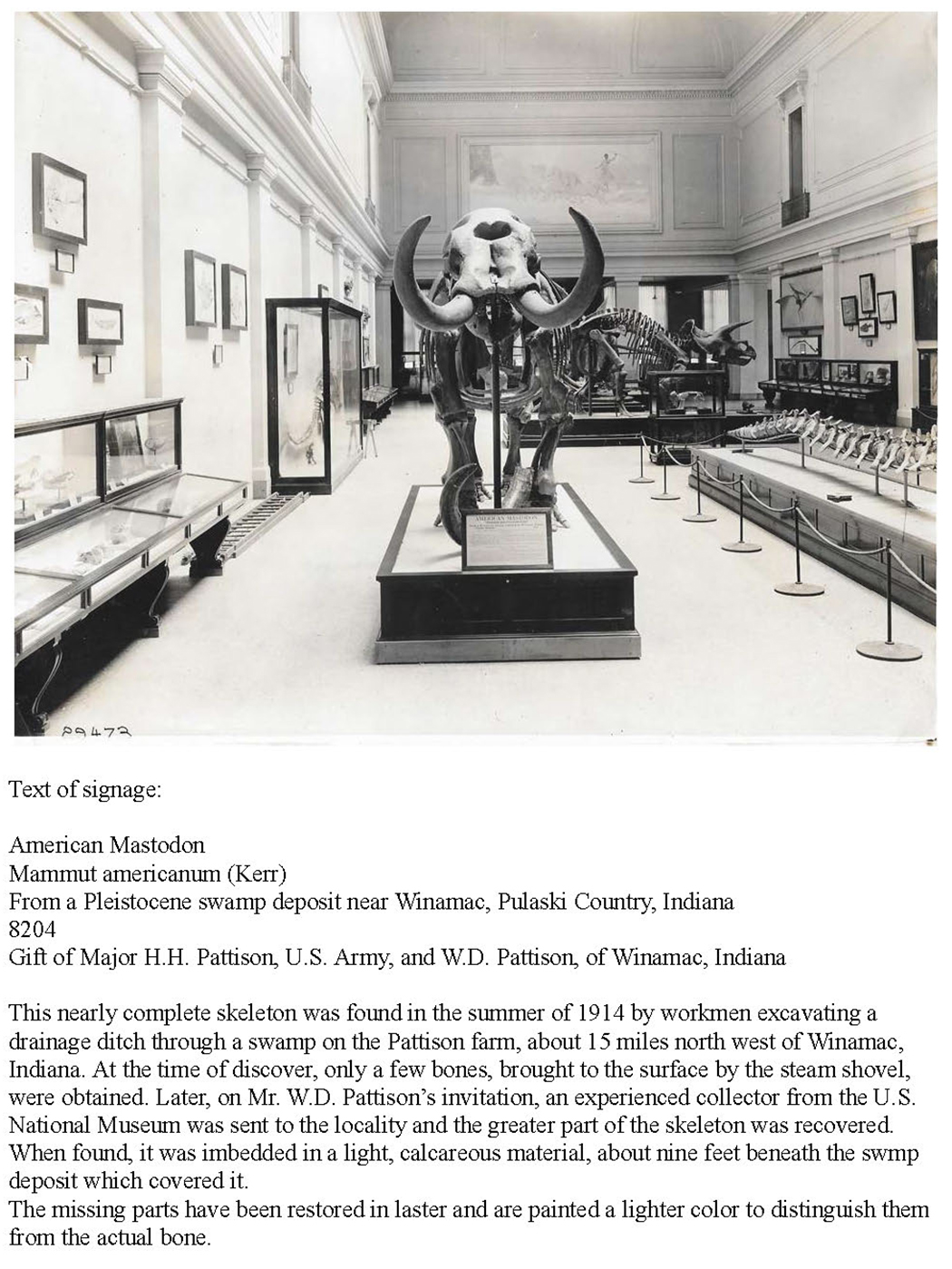

AMERICAN MASTODON

MAMMUT AMERICANUM (KERR)

From a Pleistocene Swamp Deposit near Winamac,

Pulaski County, Indiana 8,204

Gift of Major H. H. Pattison, U.S. Army, and W. D. Pattison of

Winamac, Indiana

This nearly complete skeleton was found in the summer of 1914 by workmen excavating a drainage ditch through a swamp on the Pattison farm, about 15 miles northwest of Winamac, Indiana. At the time of discovery only a few bones, brought to the surface by the steam shovel, were obtained. Later, on Mr. W. D. Pattison’s invitation, an experienced collector from the U.S.

National Museum was sent to the locality and the greater part of the skeleton was recovered. When found, it was imbedded in a light, calcareous material, about nine feet beneath the swamp deposit which covered it.

The missing parts have been restored in plaster and painted a lighter color to distinguish them from the actual bone. Mounted by T. J. HORNE under the direction of J. W. GIDLEY.

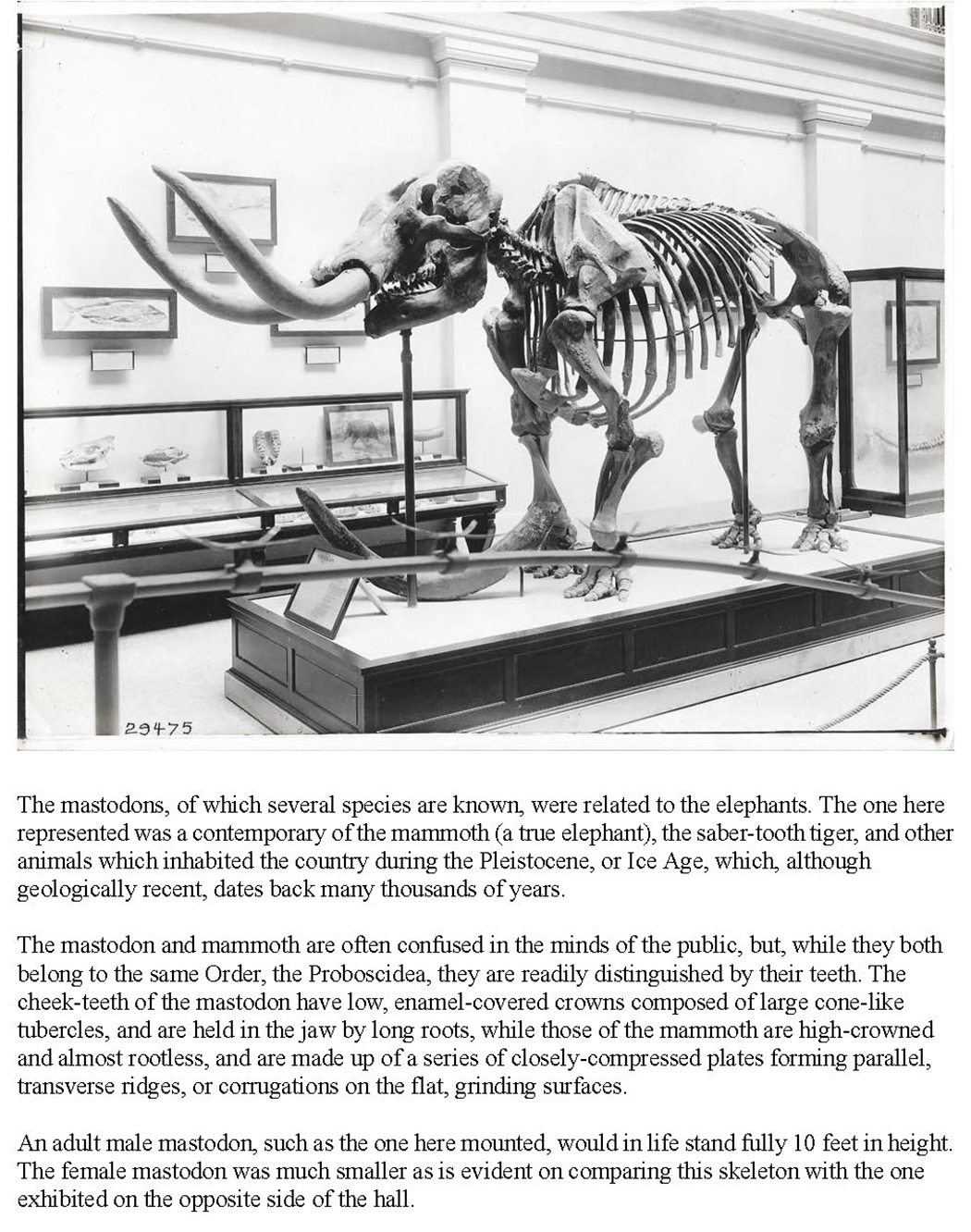

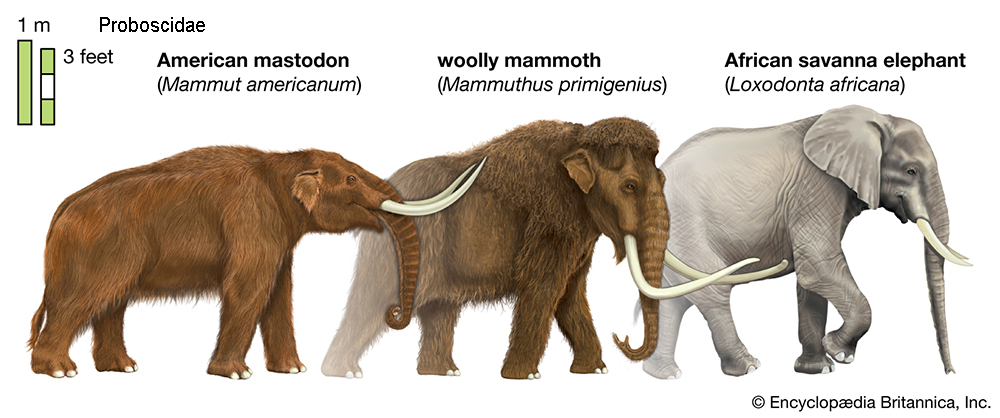

The mastodons, of which several species are known, were related to the elephants. The one here represented was a contemporary of the mammoth (a true elephant), the saber-tooth tiger, and other animals which inhabited the country during the Pleistocene, or Ice Age, which, although geologically recent, dates back many thousands of years. The mastodon and mammoth are often confused in the minds of the public, but, while they both belong to the same Order, Proboscidae, they are readily distinguished by their teeth. The cheek-teeth of the mastodon have low, enamel-covered crowns composed of large, cone-like tubercles, and are held in the jaw by long roots, while those of the mammoth are high-crowned and almost rootless, and are made up of a series of closely-compressed plates forming parallel, transverse ridges, or corrugations on the first grinding surfaces.

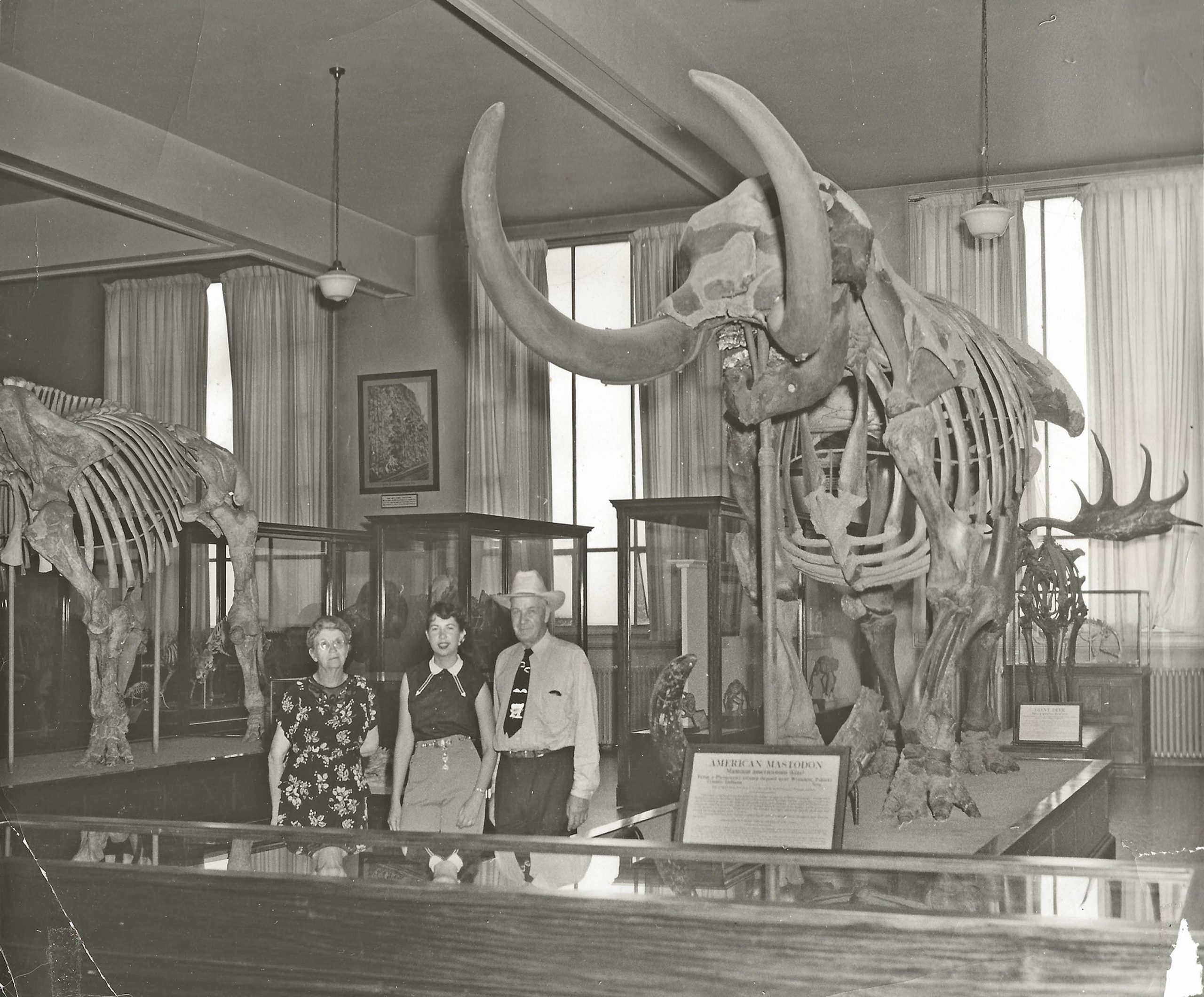

An adult male mastodon, such as the one here mounted, would in life stand fully 10 feet in height. The female mastodon was smaller, as is evident on comparing this skeleton with the one exhibited on the opposite side of the hall.*

An adult male mastodon, such as the one here mounted, would in life stand fully 10 feet in height. The female mastodon was smaller, as is evident on comparing this skeleton with the one exhibited on the opposite side of the hall.*

[*While an accompanying photograph to this web article shows both the Pulaski County mastodon and the smaller female, it is only a coincidence that we have it. The photograph in question was taken in 1953; it is unknown when it came to be in the possession of PCHS.]

It can further be said that in this same Blue Sea marsh about a mile from where the skeleton of the mastodon was unearthed, laborers, while grading a highway, excavated and found four or five large ribs of other large, prehistoric animals which were not sufficient to construct the skeleton of the animal to which they belonged.

From Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 66, 1917, The Indiana Mastodon

Each year the Museum receives reports of many finds of mastodon and mammoth remains, especially from different localities in those States bordering on the Great Lakes. These “finds,” which come for the most part from swamp deposits of the Pleistocene, usually consist of a few isolated bones or teeth, but they give evidence of the great abundance of these larger creatures which roamed over this continent during the geological age just preceding the present. Compared, however, with the great number of remains found, complete skeletons are rare. This is due in large part to the fact that by far the greater number of the finds are made by men of no experience in collecting and usually little or no knowledge of what they are finding. The National Museum is therefore fortunate in the recent acquisition of a fine, nearly complete adult male mastodon skeleton from a swamp deposit in northwestern Indiana.

Each year the Museum receives reports of many finds of mastodon and mammoth remains, especially from different localities in those States bordering on the Great Lakes. These “finds,” which come for the most part from swamp deposits of the Pleistocene, usually consist of a few isolated bones or teeth, but they give evidence of the great abundance of these larger creatures which roamed over this continent during the geological age just preceding the present. Compared, however, with the great number of remains found, complete skeletons are rare. This is due in large part to the fact that by far the greater number of the finds are made by men of no experience in collecting and usually little or no knowledge of what they are finding. The National Museum is therefore fortunate in the recent acquisition of a fine, nearly complete adult male mastodon skeleton from a swamp deposit in northwestern Indiana.

This specimen was donated to the National Museum by Mr. W. D. Pattison of Winamac, Indiana, and Captain H. H. Pattison, U.S. Army, on whose farm, about 13 miles northwest of Winamac, it was found.

A part of the skull, four limb bones, a few ribs and vertebrae, were unearthed by a dredge crew while excavating a drainage canal on the Pattison farm in the spring of 1914. On learning of the discovery, Mr. Pattison took immediate steps to preserve these bones, but before he could prevent it a few of them were carried away as curiosities by people of the vicinity. These were, however, for the most part recovered. Mr. Pattison, recognizing the value for public exhibition of such a specimen if properly handled, and judging correctly that the greater part of the skeleton might be secured by an experienced collector, very generously packed and shipped the bones then in his possession to the National Museum, at the same time extending an invitation to the Smithsonian Institution to send an expedition to his farm to recover, if possible, the remaining parts of the skeleton. A small appropriation was set aside for this purpose, and the first expedition to the Pattison farm, under the direction of J. W. Gidley of the National Museum, was undertaken in June 1915. This resulted in securing the lower jaws, most of the remaining vertebrae and ribs, parts of the pelvis, and a few more limb and foot bones. The undertaking was too extensive for the funds then available, and Mr. Gidley was obliged to return to Washington before the search was completed. Most of the bones secured on this trip were found in working over the material thrown out by the steam shovel on either side of the ditch at the time the dredging was done.

In October a second appropriation was made available, and Mr. Gidley again visited the locality of the find, this time completing the work which resulted in securing from the undisturbed deposit at the bottom of the ditch the last of the missing sections of the vertebral column, several more foot bones, and other important fragments.

At this time, it was necessary to sink a coffer-dam across the ditch, which is about 20 feet wide, and at this place contains about six feet of water and mud before coming to a hard sand bottom. Mr. Gidley thus was enabled to study the formation and make an accurate estimate of the conditions of deposition of the skeleton.

On assembling in the laboratory, the bones of this skeleton received from all sources, it has been found that, with comparatively little artificial restoration, a much more than usually fine and complete specimen of the American mastodon can be assembled. This is now being mounted and will soon be placed on exhibition as one of the striking features of the Fossil Vertebrate Hall.

Correspondence from the Richard Dodd Files

June 20, 1915

[This letter is handwritten and may not have been copied correctly.]

Letterhead: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, Washington, D.C.

Dear Doctor Merrill:

I think Mr. Siberling’s present address is Barker, Montana (either Barker or Barber), but a letter to Shawmut, where he is well known, with request to forward, would surely reach him.

Rain has delayed me one day, but I am progressing with the work here. Yesterday I took a man out to the Pattison farm where the bones were found (It is about 15 mi nw of Winamac) to size up the situation and get an estimate of the amont and cost of labor required. We got some small pieces of the skull from the ditch grade and a good dorsal vertebra from the muck in the ditch, but did not have the proper tools to explore for bones in the marsh bed from which the bones were taken in excavating this ditch. Am having some light steel rods made and am sure that in another day we will be able to locate some bones if they are there. The prospect looks good now but this undertaking, unless the remaining bones lie rather compact (that is are not much scattered about in their original matrix), this undertaking is going to be rather large, and I fear our small appropriation will not be sufficient. Will report to you more fully about that in a day or two.

This ditch is about 15 ft wide and in the middle about 8 or 9 ft deep, the lower 4 ft being filled with water and loose muck. The bones lie in a stratum of [?] marsh about 3 ft thick and 6 ft beneath the original surface of the swamp deposit. This marshy substance is firm but can easily be explored with a sharpened iron rod. This of course we will do before trying any excavating, and if no bones are found no excavating will be done. If we find any good bones we will then know what we are going after and about what work will be required to get there.

Very truly yours,

J.W. Gidley

July 10, 1915

Dr. Richard Rathburn, Assistant Secretary, U.S. National Museum

Dear Sir:

In compliance with instructions of detail of June 10, 1915, I proceeded (leaving Washington June 16, and returning June 26) to Winamac, Indiana for the purpose of recovering as much as possible of the remaining parts of a skeleton of Mastodon a few bones of which had been collected and sent as a gift to the National Museum by Mr. W. D. Pattison and Capt. H. H. Pattison, U.S.A. last winter. The trip was a decided success as a greater number of the missing bones were recovered sufficient to insure the mounting for exhibition of a more than usually large skeleton of Mastodon. The work was not completed, however, owing to lack of funds, the $150 allotted not being sufficient to do the work necessary to make an exhaustive search for the tusks, foot-bones and two limb-bones which are still missing. It is hoped that this work may be again taken up and completed at a very early date.

This skeleton was first discovered more than a year ago by dredge workers who were excavating a drainage ditch through a swamp on the Pattison farm about fifteen miles north west of Winamac, Indiana. On arriving at the locality the first cursory look over the place was far from encouraging. Standing on the bank of a partially water filled ditch twenty feet in width, flanked on either side with a low continuous mound of soft half dried muck thrown up by the dredge scoop and now partially overgrown with woods and willows. There was nothing save a few very small weathered fragments lying about on the dupp [?] to indicate that there ever had been any bones in the vicinity. Since there was no way of draining the ditch except at considerable expense, I made preparations the next day to explore the muck deposit for bones both in the ditch and along its borders by means of steel rods. This method proved successful and in a days time I had the situation pretty well sized up. By probing with the steel rod I found a bone here and there in the muck piles thrown out by the shovel and the next day set to work four men with shovels and about forty feet up and down the ditch on either side were carefully dug over recovering many bones and revealing the fact that a great part of the skeleton, including the lower jaws, most of the vertebrae and some of the limb bones and ribs had been thrown out of the ditch by the shovel unnoticed by the workmen. A few bones, including one sepula and a large portion of the left pelvic bone were located and moved from the bottom of the ditch where they lay still partially imbedded in the original marl deposit just below the reach of the dredge shovel.

As mentioned above the tusks and many of the important foot bones were not found, yet all indications point almost to a certainty that these are still lying some where in the bottom of the ditch and could be recovered by a system of coffer-damming which could easily be done at a comparatively low cost when the value of the results if successful are considered.

While on the ground I got an estimate of Mr. F. M. Williams a bridge contractor of Winamac as to the probable cost. His figures would not exceed as a maximum two hundred fifty dollars ($250), or might be as low as one hundred fifty dollars ($150) according to the amount of ditch necessary to be worked over. Add to this a maximum of seventy five dollars ($75) traveling expenses (this would be ten ($10) or fifteen ($15) dollars less according to the number of days required to do the work) and the total cost would not exceed three hundred twenty five dollars ($325) while it might not exceed two hundred ($200).

Judging from the good state of preservation of the bones found these tusks, which are at least seven inches in diameter at the base and not less than nine or ten feet long, should be in splendid condition and would add at least a hundred percent to exhibition value of this fine skeleton. It is therefore strongly urged, if the necessary funds can be made available that further search be made for the missing parts.

I wish here to inform you especially of the generosity and extreme good will of Mr. W. D. Pattison, who, while I was in Winamac did what he could to further my work, extending what courtesies he could and giving most willing permission to do whatever we chose with the drain ditch in making further search for the tusks.

Very respectfully,

(Through Doctor Merrill.)

July 14, 1915

My Dear Mr. Pattison:

I have delayed writing you hoping to get some definite word from the Ward Nat. Sci. Establishment regarding the mastodon teeth they purchased from Mr. Fite. They seem unable to decide from the casts of ours which I sent them, so they are forwarding to us the teeth for actual comparison. Will let you know results as soon as they arrive.

The bones I shipped from Winamac arrived in good condition a little over a week ago. They have been unpacked, and the boys in the laboratory are now busy cleaning them and getting the broken pieces properly assembled. The pelvis is making up nicely, there being but very few fragments missing. When properly put to gether [sic] it measures about 6ft. across. Some hind-end, what? The Museum authorities are so delighted with the results of this trip I have had little trouble in getting another allotment to go out there and complete the search for these missing tusks. Dr. Merrill told me this morning that the requisition had gone through and that the money was available any time I think best to again tackle the job. I am writing Mr. Williams to get his jugement [sic] as to the best time to begin the work.

With very pleasant recollections of my recent visit to Winamac, I am with kindest regards,

Very sincerely yours,

[the letter ends without a signature]

August 9, 1915

Mr. J. W. Gidley, Washington, D.C.

My dear Mr. Gidley:

I ship to you to-day by express (pre-paid) one box containing a few more mastodon bones, obtained from some neighbors.

Did you write the Field Museum about the leg bones?

Hope to see you before long.

Yours respectfully

W.D. Pattison

P.S. There was much rainfall during July.

W.D.P.

August 13, 1915

Mr. W.D. Pattison, Winamac, Ind.

My dear Mr. Pattison:

The box of bones you sent came O.K. and were unpacked yesterday. They help out a lot. Thank you so much for sending them. It was very good of you to take the trouble. We are centainly having good luck getting back the bones that were carried away.

I have not yet written the Field Museum, but have been keeping the mails busy between here and Rochester N.Y. with the result, as you already know, of getting the molar teeth, and later I persuaded Ward to send on a humerus (the biggest bone of the fore leg) which he said he had received with the Fite collection. This proves to be, without question, the mate to the one you sent us in the first shipment, and incidentally proves that Fite was lying to us in his statement that he had received from Davis only the two teeth. Maybe when I come out again again [sic] get at Fite or Davis and get the truth as to what disposition they made of the other large limb bones, two of which are still missing.

I am hoping that the weather will settle down soon and give us a dry spell, as I am anxious to get after those tusks.

Very sincerely yours,

[no signature]

My regards to Mr. Spanger and Mr. Williams when you see them. Will write Williams soon regarding arrangement for [cannot read] work out the ditch.

October 29, 1915

Letterhead: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, Washington, D.C.

Dear Dr. Merrill:

On my recent trip to Indiana I had the good fortune to complete the vertebral column of our fine mastodon skeleton besides recovering several other important fragments which help out nicely with our restoration. Diligent and thorough search, however, failed to discover the missing tusks in the ditch on the Pattison farm.

With these facts you are already familiar as well as with the details of my inquiry in the neighborhood of the find which has led me to believe that the tusks, and probably some of the other bones, were stolen at the time the other parts disappeared, which we traced to and afterward recovered from Rochester N.Y., and that these or at least part of them also found their way to the same place.

In corresponding with Mr. F. H. Ward, of the Wards Nat. Sci. Establishment, I find that a large tusk and some other bones sent to him by Mr. Fite from Indiana, are still there at their Establishment. Under the circumstances, which I have already explained to you in detail, it seems to me advisable that I go to Rochester, should you approve the detail, and make careful examination and comparisons of this material. Should it or part of it prove to belong to our skeleton I probably could then make some mutually satisfactory arrangement for exchange, which of course would be subject to your approval and would would [sic] be submitted to you on my return.

This detail would not take more than one day of my time from the Museum, and would cost about $26. There still remains unexpended of my original allotment $57.35,; this of course would much more than cover the expenses of the proposed trip to Rochester.

Very respectfully,

W. Gidley

September 8, 1980

Letterhead: National Museum of Natural History * Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 * Tel 280-357-2229

Letterhead: National Museum of Natural History * Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 * Tel 280-357-2229

Mr. Richard R. Dodd, (address included)

Dear Mr. Dodd:

The mastodon from Pulaski County, Indiana, USNM 8204, has been on exhibit continuously since the Museum acquired it. Currently it is featured prominently in our exhibit hall, “The Ice Age and the Emergence of Man.”

We are enclosing a 35mm color transparency of the specimen, with our compliments.

We are also sending you copies of the correspondence surrounding the venture of 1915 – we hope you enjoy reading it as much as we did.

Sincerely yours,

Raymond T. Rye, II, Museum Specialist, Department of Paleobiology

Newspaper Articles