If you read the earlier episodes on this site of Casimir Pulaski, you will remember that he was described as a man of contradictions. There are several possible dates of birth, places of birth, dates of death, places of death, confusion of titles … I could go on.

If you read the earlier episodes on this site of Casimir Pulaski, you will remember that he was described as a man of contradictions. There are several possible dates of birth, places of birth, dates of death, places of death, confusion of titles … I could go on.

Now, we will go into the contradictions of his banner.

It’s a fun trip through history, and if you read both the local news item and the item pulled from The New York Times written in 1880, you will find… contradictions.

From the Pulaski County Journal…

… cut out from paper, and date not shown, probably written in 1976, Laura Dodd Reproduces Count Pulaski’s Banner

Laura Dodd, a teacher at Winamac Elementary School, spent hours of research and painstaking embroidery to make a replica of General Pulaski’s battle banner. She made it as her contribution to the Bicentennial (1976) after her husband, Dick Dodd, obtained information about it.

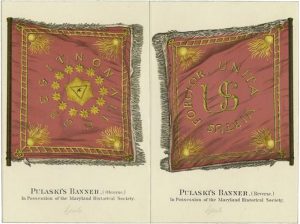

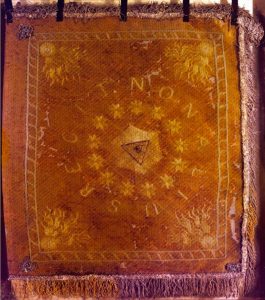

Mrs. Dodd stated the original banner “was made of double crimson silk with designs on each side, embroidered in yellow silk. The letters were shaded in green.” Her replica is made of red polyester material and is embroidered in yellow and white; it is shaded and fringed with green. Mrs. Dodd based her colors on a color photograph of the flag and was certain her colors were authentic.

According to Mrs. Dodd, Pulaski and his family were very religious, and his sister was a nun. “He went to the Moravian sisters in Bethlehem, Pa., and asked them to make him a flag.” Further, she said, “The banner was made for and presented to him after he had raised and organized an independent corps of 68 horses and 200 foot soldiers at Baltimore, Md., in 1778. He bore the banner with him until he fell in Savannah. The banner was saved by his lieutenant and eventually reached Baltimore after the close of the war. It was used in the procession that welcomed LaFayette to that city.”

The original banner is now preserved in the Maryland Historical Society.

Mr. and Mrs. Dodd

Mr. Dodd was born and raised in Indianapolis, Mrs. Dodd in Georgia. According to those who knew them, the Dodds were very proud of their adopted county.

The Pulaski County Public Library produced this information about Mrs. Dodd: Laura Ellen “Lolly” Hancock Dodd (1916 – 2001), was a teacher at Eastern Pulaski Elementary School for 21 years, retiring in 1979. She was a member of the First United Methodist Church, United Methodist Women, Pulaski County Retired Teachers Association, Delta Sigma Tau, Pulaski Memorial Hospital Auxiliary, Gleaners Circle, Delta Kappa Gamma and the Pulaski County Historical Society.

Her husband, Richard “Dick” Dodd (1913 – 2001), was a typesetter for the Pulaski County Democrat when he was inducted into the United States Army. He served in New Guinea and the Philippines and was discharged with the rank of Master Sgt. He returned to Winamac, moved to Mooresville where he published a local newspaper, and returned to Winamac in 1950 to work at the Democrat. He continued there until the paper (now The Pulaski County Journal) was sold in 1970. He was an Associate Editor at the time of his retirement. He won election to Clerk of Pulaski Circuit Court, serving two terms from January 1970 to December 1978; and was a Winamac Town Board member (1954-59), a member of the Winamac Town Plan Commission and a member of the Monroe-Winamac Library Board. He was a member of the First United Methodist Church, Indiana Historical Society, charter member and first president of the Pulaski County Historical Society, president of Winamac Kiwanis Club, division lieutenant-governor of Kiwanis International, and a 1981 recipient of the Chamber of Commerce H.J. Halleck Award for Community Service.

From The New York Times, July 18, 1880

…”The Interesting Relic of the Revolution Now in the Possession of the Maryland Historical Society,” reprinted from The Baltimore Sun.

This item is being copied in its entirety, interesting both for the manner in which it was written (sentences as long as paragraphs, paragraphs as long as pages), and for its historical inaccuracies. This article both perpetuated and tried to correct some of the inaccurate rumors about Pulaski’s death and his banner. The banner, in this article, is the main attraction.

Among the most interesting treasures of the Maryland Historical Society is a relic of the Revolutionary War, the banner of Pulaski, which the poet Longfellow has embalmed in verse. Probably there is no poem in the language better remembered by American youth than Mr. Longfellow’s “Hymn of the Moravian Nuns of Bethlehem at the Consecration of Pulaski’s Banner.”

Among the most interesting treasures of the Maryland Historical Society is a relic of the Revolutionary War, the banner of Pulaski, which the poet Longfellow has embalmed in verse. Probably there is no poem in the language better remembered by American youth than Mr. Longfellow’s “Hymn of the Moravian Nuns of Bethlehem at the Consecration of Pulaski’s Banner.”

The banner of Pulaski, preserved in Baltimore, is 20 inches square, made to be carried on a lance. It is of double silk, now so much faded and discolored by time that its color, whether originally crimson or white, cannot be determined. On both sides designs are embroidered with what was yellow silk, shaded with green, and deep silk fringe bordering. On one side are the letters, “U.S.,” and in a circle around them the words “Unita Virtus Forcior;’ on the other side in the center is embroidered an All-seeing Eye, and the words, “Non Alius Regit.”

While historical research has brushed away nearly all the pretty garniture which Mr. Longfellow had thrown around this interesting relic, the fact remains pretty well substantiated that Pulaski procured his banner in Bethlehem, of the Moravian Sisters, who did not lead a cloistered life, and who really sold their work to help support their house. But for Baltimoreans the relic has even a greater interest than if it had been consecrated as described by the poet, for it is the flag of a legion recruited in Baltimore and brought out of the fire of the siege of Savannah by a Baltimorean.

The Count Pulaski had, with the assent of Congress and General Washington, been commissioned to organize an independent corps of 68 horse armed with lances, and 200 foot equipped as light infantry. He was allowed also the privilege of enlisting men in any State, with the Continental bounty, and to include prisoners and deserters. He established his recruiting headquarters in Baltimore, and the Legislature of this State placed his legion on the same footing in Maryland with other Maryland regiments, and rendered him all the assistance necessary in the work. General Smallwood afterward complained that Pulaski was getting his men, but the Council of State did not interfere. In about six months the gallant Pole reported his whole force to be 830 men, which was about 50 more than had at first been proposed.

They were organized into three companies of horse and three of infantry, which were publicly reviewed in the city, and afterward joined Washington in New jersey, and on the march to Little Egg Harbor his camp was surprised by the betrayal of a deserter, and 40 men, including Lieut. Col. De Bosen were bayoneted. In his subsequent operations in the South, Pulaski received his mortal wound in the groin from a swivel shot at the siege of Savannah, October 9, 1779. Capt. Bentalou, of Baltimore, was wounded at the same time, and they were both conveyed on board the United States brig Wasp, then with the French fleet, Pulaski dying two days afterward, just as the brig was leaving the mouth of the Savannah River, and his body was committed to the waves. Capt. Bentalou was safely conveyed to Charleston, where he recovered, and was afterward, in 1826, accidentally killed in Baltimore by a fall through the hatchway of a warehouse.

It was while Gen. Lafayette was sick at Bethlehem, according to some, that Pulaski went from Baltimore to visit him, where he procured the banner, which, at his death, was saved by Capt. Bentalou, and finally deposited in Peale’s Museum, which formerly stood on the northwest corner of Baltimore and Calvert streets, in this city. In 1844, Edmund Peale presented it to the Maryland Historical Society, where, as stated above, it is treasured. Some five or six years ago Mr. Henry Stockbridge, member of the Maryland Historical Society, who became interested in the history of the banner, addressed some inquiries to the Moravian Bishop De Schweinitz on the subject, receiving a reply, which is recorded in the minutes of the society as follows:

Bethlehem, Penn., Sept. 2, 1874, Henry Stockbridge, Esq., Baltimore: Dear Sir: I am afraid you will imagine I have forgotten to carry out my promise and examine our records for information touching the Pulaski banner. Such, however, is not the case. Early in the Summer my duties prevented me from giving this subject the proper attention, and afterward I spent several weeks at the sea-shore, returning last month. I am now prepared to give you an answer to your question and my opinion with regard to the banner. From what you have written, I believe that such a banner was embroidered by the inmates of the Moravian Sisters’ House at Bethlehem, but it was not formally presented by them to Pulaski; indeed, it was not a gift at all, but made to order and paid for by him. This is my opinion, and this is based upon the following facts:

Again, I have found in our archives the official journal of the Superintendent of the Sisters’ house, in which the banner was embroidered. This document does not make the most distant allusion to Pulaski or to a banner. Had one been presented to him, the fact would have, as a matter of course, been mentioned in this journal, or had they sent it after his departure as a gift, this, too, would certainly have been recorded. Now, at that time a part of the income of the Sisters’ house with which it was supported and depended upon the sale of embroidery and other fancy work made by the inmates. They received large orders for such work. This was so common a thing that no notice of such orders was taken in the official diaries. Hence, I believe that when Pulaski visited the Sisters’ house, in the Spring of 1778, and saw the beautiful embroidery which was done there, he ordered a small cavalry banner for his legion, and that the whole transaction was a simple business one, which received the turn now generally accepted through Longfellow’s utterly unhistorical poem.

A number of years ago a young Bethlehemite, who was studying at Yale College, met Prof. Longfellow and told him that there had been no cathedral at Bethlehem in Pulaski’s time, and that there was none there now; that the Moravians had never had monasteries, and that there had never been Moravian nuns, the whole history of the Church being a protest against everything Romish, whereupon the Professor smilingly said that his description was a “poetical license.” Last year an old gentleman lived here who used to say that when a child he had been acquainted with one or two of the women who had helped to embroider the Pulaski banner. This is another proof that such a banner was actually embroidered here. The above is all the information I am able to give. I remain, dear Sir, very respectfully yours, Edmund De Schweinitz.

Fun Fact

The Moravian Sisters of Bethlehem, a couple of decades before the Revolutionary War (1748), were given a house discarded by the Moravian Brothers. These were not cloistered sects. They were not nuns and priests, but women and men living independently of their families.

The Brothers were graced with a new house. The house that is now the oldest building in Bethlehem, the one that is now part of the Historic Moravian Bethlehem Historic District, designated as a National Historic Landmark District (2012) and is named to the U.S. Tentative List for nomination to the World Heritage List (2016), is the hand-me-down Sisters’ house.

Sisters rule.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Longfellow was a popular poet of his time, the mid-1800s. He wrote historical poetry that was known to be light on historical fact. This poem – not to commemorate Pulaski but to commemorate his banner, although the title leads us to believe it is to commemorate the Moravian Nuns of Bethlehem – was written in 1839. This was years before two of his more well-known poems, The Song of Hiawatha (1855) and Paul Revere’s Ride (1860). And yet, in 1839, he was popular. So popular that this poem rewrote the history of the banner, adding yet another contradiction to Pulaski’s story.

When the dying flame of day

Through the chancel shot its ray

Far the glimmering tapers shed

Faint light on the cowled head;

And the censer burning swung,

Where, before the alter, hung

The crimson banner, that with prayer

Had been consecrated there.

And the nuns’ sweet hymn was heard the while,

Sung low, in the dim, mysterious aisle.

“Take thy banner! May it wave

Proudly o’er the good and brave;

When the battle’s distant wail

Breaks the sabbath of our vale.

When the clarion’s music thrills

To the hearts of these lone hills,

When the spear in conflict shakes,

And the strong lance shivering breaks.

Take the banner! And beneath

The battle-cloud’s encircling wreath,

Guard it, till our homes are free!

Guard it! God will prosper thee!

In the dark and trying hour,

In the breaking forth of power,

In the rush of steeds and men,

His right hand will shield thee then.

“Take thy banner! But when right

Closes round the ghastly fight,

If the vanquished warrior bow,

Spare him! By our holy vow,

By our prayers and many tears,

By the mercy that endears,

Spare him! He our love hath shared!

Spare him! As thou wouldst be spared!

“Take thy banner! And if e’er

Thou shouldst press the soldier’s bier,

And the muffled drum should beat

To the tread of mournful feet,

Then this crimson flag shall be

Martial cloak and shroud for thee.

The warrior took that banner proud

And it was his martial cloak and shroud!