Moving on in time, we have come to the Revolutionary War. The Potawatomi were not directly involved in this war, but they were certainly affected.

On this particular website, which is devoted to the history of Pulaski County and the Potawatomi who settled here, we will do our best to summarize the events in terms that describe the continued displacement of Native Americans, in particular, the Potawatomi.

Atrocities were committed on both sides. Those atrocities will not be detailed, but summarized. Please forgive the emphasis placed on the atrocities committed by the Continental Army. We are trying to explain Native displacement.

For Whom Did Native Americans Fight?

In July 1776, the British had not yet unleashed Native warriors on the frontiers. In fact, the Stockbridge Indians of western Massachusetts, who were among the first to get involved in the Revolution, joined Washington’s army, fighting against the British. Most Natives tried to stay neutral in what they saw as a British civil war. Eventually, however, most sided with the British.

They were not fighting against freedom. Like the American patriots, they fought to defend their freedom as they understood it. In their eyes, aggressive Americans posed a greater threat than did a distant king to their land, their liberty, and their way of life.

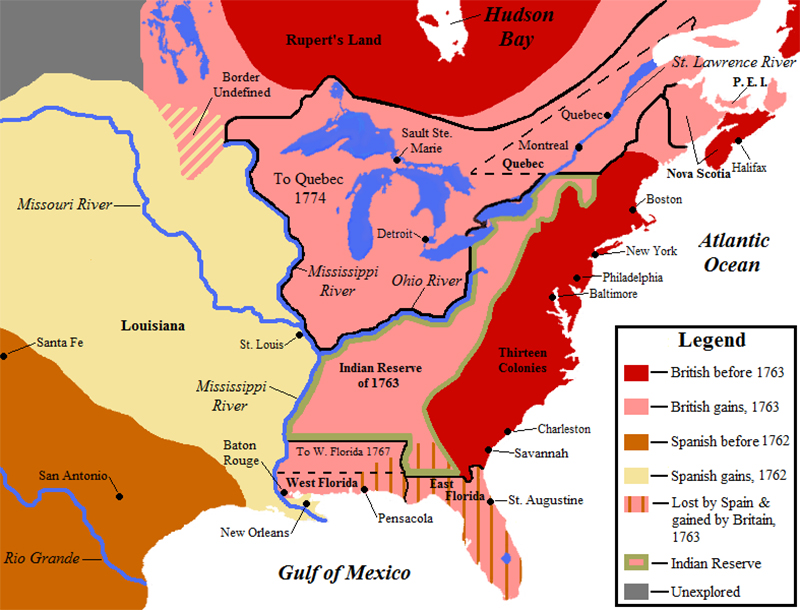

Even before the War, colonists were angry with the British government’s actions. The British established a reservation west of the Appalachian Mountains, hoping to keep the Natives to the west and the colonists to the east. The colonists resented it, accusing the King of preventing colonists from moving west.

Colonists were angry, also, that the King had encouraged “the merciless Indian Savages” by allowing them to raid white settlements. Britain had a network of forts and trading posts on the frontiers (i.e., Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit). From these bases, British officers encouraged Native Americans to launch raids on communities that supported the rebel cause.

But let’s back up a few centuries.

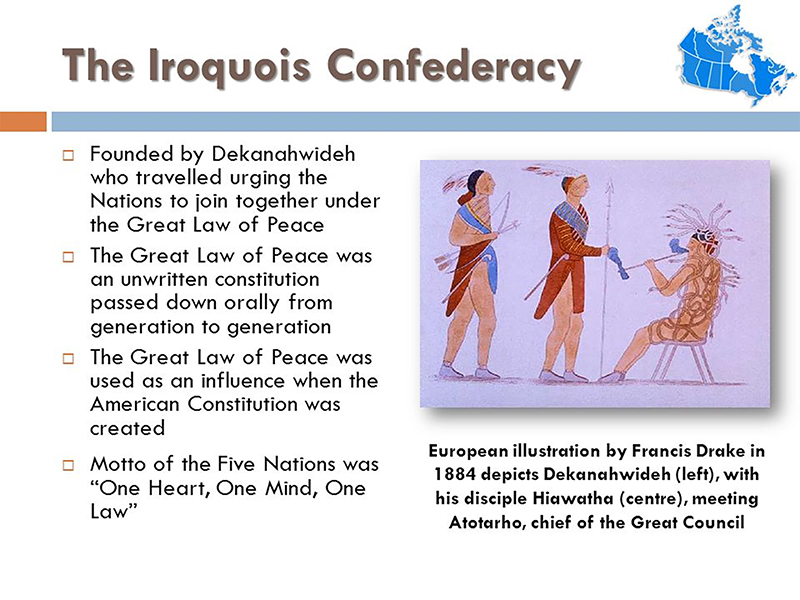

How the Iroquois Great Law of Peace Shaped U.S. Democracy

The ancient Iroquois “Great League of Peace” led to the formation of the United States of America’s representative democracy.

Centuries before Europeans arrived, the Iroquois nation, located along the Southern Great Lakes, was fragmented into five warring tribes: Onondaga, Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga and Seneca. They shared a common language and culture, but they fought over territory.

Hiawatha was an Onondaga chief enshrined in a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Like all his poems, Longfellow’s beautifully written work was only loosely based on historical fact. However, because of the poem, we remember the name.

Hiawatha was a follower of a man known as the Great Peacemaker. It was seen as a mark of respect not to refer to this man by his name. For purposes of this site, we’ll leave it at the title. It is known that the Great Peacemaker had a speech impediment. While the ideas he proposed were his, he relied on Hiawatha, a great orator, to present his plans.

History claims the Iroquois Confederacy was founded by the Great Peacemaker in 1142, thus, it is the oldest living participatory democracy on earth. The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha traveled among the five tribes to present their plan, the Great Law of Peace. It united the five nations into a League of Nations, the Iroquois Confederacy. Each nation maintained its own leadership, but they agreed that common causes would be decided in the Grand Council of Chiefs. The concept was based on peace and consensus.

Their constitution, recorded and kept alive on a two row wampum belt, held many concepts familiar to United States citizens today:

- A restriction on holding dual offices,

- Processes to remove leaders within the confederacy,

- A bicameral legislature with procedures in place for passing laws,

- A delineation of power to declare war, and

- A creation of a balance of power between the Confederacy and individual nations.

Their constitution also presents the seventh-generation principle, which dictates that decisions that are made today should lead to sustainability for seven generations into the future.

In 1744, Benjamin Franklin had occasion to hear an Onondaga Chief give a speech urging the contentious thirteen colonies to unite. He printed the speech and used it as he presented his Plan of Union at the Albany Congress in 1754. Franklin invited members of the Great Council to address both this Congress and the Continental Congress in 1776.

There is some historical claim that the Continental Congress, during the Revolutionary War, feared the collective of the Iroquois Confederacy. Historians claim this fear was a causative factor in Sullivan’s Expedition, which you will read about shortly.

Side Note: One could become confused about the Five Nations and the Six Nations. During the Beaver Wars of the 1600s (spoken of in an earlier page on this website), we spoke of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. During the Revolutionary War, the reference is always to the Six Nations. In 1722, the Confederacy was joined by the Tuscarora.

Native American War for Independence

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson clearly described the role of Native Americans in the American Revolution. Per Jefferson, in addition to his other oppressive acts, King George III had “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” Jefferson inscribed into this sacred text the words that placed Native Americans on the wrong side of history from the very beginning of the Revolution.

When the Revolution broke out, Native Americans knew their lands were at stake. The Cherokees had every reason to be concerned. For more than half a century, they had seen their lands in Georgia, eastern Tennessee, and western North and South Carolina whittled away in treaty after treaty with the colonies, and the tempo of land loss escalated alarmingly in the late 1760s and 1770s.

Young Cherokee men, frustrated by their fathers’ policies of selling land, were determined to prevent further erosion of the Cherokee homeland. They seized the outbreak of the Revolution as an occasion to drive trespassers off their lands. Cherokee warriors attacked frontier settlements in 1776, but they did so on their own, without British support and against the advice of British agents who urged them to wait until they could coordinate with His Majesty’s troops. American forces immediately retaliated, burning Cherokee towns and forcing Cherokee chiefs to sue for peace, which they did at the cost of ceding even more land.

The Revolution divided the Iroquois Confederacy as well. The Six Nations constituted the dominant Native power in northeastern North America, but the Revolution shattered the unity of the League. Mohawks supported the Crown, but the Oneidas leaned toward the colonists. At the Battle of Oriskany in 1777, Oneidas fought alongside the Americans, while Mohawks and Senecas fought with the British, a devastating development for Iroquois society that was built around clan and kinship ties. Mohawks were driven from the Mohawk Valley and Oneidas fleeing retaliation lived in squalid refugee camps around Schenectady, New York.

At the end of war, many Iroquois relocated north of the new border into Canada rather than stay in New York and deal with the Americans. Others remained on their ancestral homeland. Formerly masters of the region, they now struggled to survive in a new world dominated by Americans.

Between the Cherokees and the Iroquois, in the territory drained by the Ohio River, Native peoples lived in a perilous situation. The Ohio Valley had been virtually emptied of human population because of intertribal wars in the seventeenth century. But it had become a multi-tribal homeland again by the eve of the Revolution. Delawares, Shawnees, Mingos, and other tribes had gravitated toward the region, attracted by rich hunting grounds and growing trade opportunities.

Pressured by colonial expansion in the east, European settlers were not far behind. Shawnee warriors were fighting to keep pioneers like Daniel Boone out of their Kentucky hunting grounds before the Revolution, and they fought in Lord Dunmore’s War against Virginia in 1774.

The Revolution turned the Ohio Valley into a fiercely contested war zone. Most Shawnee allied with the British, who had been telling them they could expect nothing less than annihilation at the hands of the Americans. Kentucky militia crossed the Ohio River almost every year to raid Shawnee villages. About half of the Shawnee migrated west to present-day Missouri, which was claimed by Spain. Those who remained moved their villages farther and farther away from American assault. By the end of the Revolution most Native Americans living in Ohio were concentrated in the northwestern region.

The Delaware were initially reluctant to take up arms or support the British. In fact, the Delaware chief, White Eyes, led his people in making the Treaty of Fort Pitt in 1778, the first Indian treaty made by the new nation. The Delawares and the United States Congress agreed to a defensive alliance. But American militiamen murdered White Eyes, their best friend in the Ohio Indian country. American authorities put out that he had died of smallpox but the damage was done. Like the Shawnee, Delaware allied with the British

Americans struck back. In 1782 a force of American militia marched into the town of Gnadenhatten. It was a community of Delaware Indians who had converted to the Moravian faith. They were Christians and they were pacifists. But all that mattered to the militia was the fact that they were Delaware. The Americans divided them into three groups—men, women, and children. Then, with the Indians kneeling before them singing hymns, they took up butchers’ mallets and bludgeoned to death 96 people. Gnadenhatten means “Tents of Grace.” Delaware warriors, later fighting as allies of the British, exacted brutal revenge for the massacre when American soldiers fell into their hands.

Sullivan Expedition

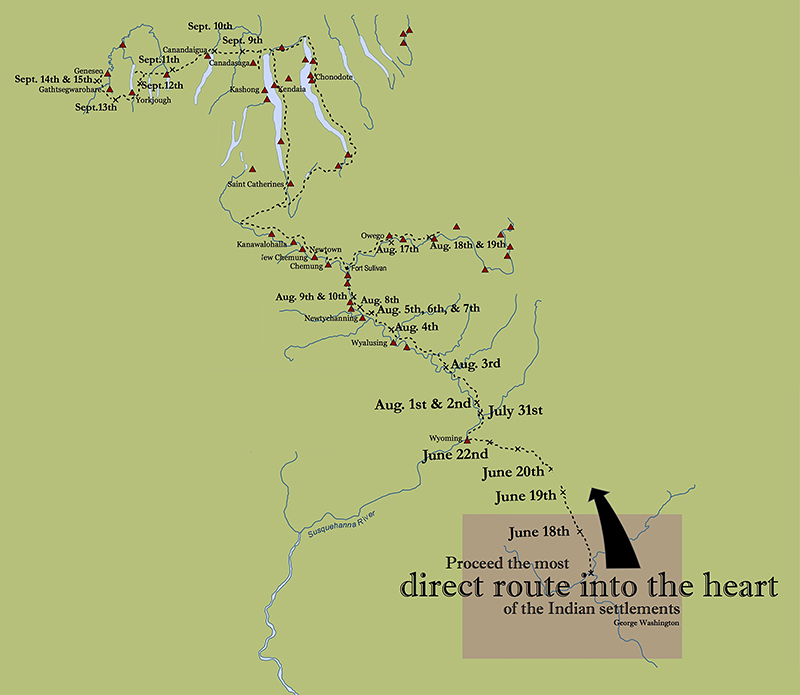

The 1779 Sullivan Expedition was one of the largest and most meticulously planned operations that the Continental Army undertook during the war. It was a scorched-earth campaign in what is now western New York State. The Continental Army attacked the entire Iroquois Nation, even the tribes that had sided with the Americans. Following are the orders given by General George Washington to General John Sullivan on May 31, 1779.

The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.

But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them.

The campaign began in June and ended in October. Forty villages were destroyed, as well as their stores of winter crops. In the end, 5,000 Iroquois retreated to Canada seeking British protection. The Iroquois were dependent on whatever the British could provide in the harsh winter of 1779. They were decimated by disease and battle. The entire area was depopulated of Native Americans, leaving it open for post-war settlement by colonists.

This campaign and others that followed opened up the Ohio Country, the Great Lakes regions, Western Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Kentucky.

Side Note: Of interest to persons who live in Pulaski County, General Casimir Pulaski was ordered to participate in the Sullivan Expedition. He became disheartened and considered giving up his commission and returning to Europe (where there was a price on his head). Instead, he asked for an appointment to the Southern Front. He was granted this request, and it was there that he lost his life, in the Battle of Savannah.

The Western Department

The Western Department of the Continental Army is often. Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Brodhead went to the Ohio Valley, which during the war covered Western Pennsylvania and Ohio, with parts of modern West Virginia, Kentucky, and New York. In addition to fighting with the British and their allied Native American tribes, the Americans in the Ohio Valley were tasked with making peace with neutral tribes and even gaining assistance from them.

Brodhead’s most important contribution to the American Revolution was the Coshocton Expedition. In this Expedition, Daniel led his men to discuss peace with the Turtle tribe of Ohio. Although there was the intention of negotiating an alliance, a battle broke out during negotiations. After retreating, Brodhead regathered his men and instead led a full-on aggressive campaign against the tribe.

Within a month, the Americans had taken the village of Coshocton and effectively secured the area.

Outcomes

The American Revolution was a double blow to Native Americans east of the Mississippi River. Many had sided with the British in the hopes they could maintain their independence. With an American victory, the British largely abandoned commitments made to their allies. Without British protection, many Native Americans were subjected to immediate encroachment from western-minded Americans who held little sympathy for Natives who had fought against them during the war.

Those who did not fight back chose to seek legal treaties with the American government. Some progress was made, and there were moments of real promise that treaties respecting Native claims would be upheld. However, there is just as much evidence to suggest such treaties would have been impossible to enforce without an armed American presence. And it just was not politically possible for an American standing army to forcibly throw off citizens moving west.

President George Washington did meet with chiefs and tribal elders on several occasions, all who looked upon Washington to honor the agreements and treaties that had been made. For his part, Washington strove for a neutral stance that tried to balance the opposing sides of Native American land claims, and that of the land claims of emerging American enterprises. Washington, himself, was the owner of lands in present-day West Virginia, then still deeply inhabited in parts by the Cherokee.

In the east, the fighting between the British and the Continental Army effectively ended after Lord Cornwallis surrendered to Washington’s army and their French allies at Yorktown in 1781. In the west, Native Americans continued their war for independence, and there, things did not go so well for the Americans. In 1782, for example, the Shawnee and other tribes ambushed and defeated Daniel Boone and a force of Kentuckians at the Battle of Blue Licks.

But the British had had enough. At the Peace of Paris in April 1783, Britain recognized the independence of the United States and transferred its claims to all the territory between the Atlantic and the Mississippi and between the Great Lakes and Florida.

There were no Native Americans at the Peace of Paris, and they were not mentioned in its terms. They were furious and incredulous when they learned that their allies had sold them out and given away their lands.

Although George Washington, his secretary of war Henry Knox, Thomas Jefferson, and other good men of the founding generation wrestled with how to deal honorably with Native Americans, the taking of their land was never in doubt. After the long war against Britain, the United States government had no money; its only resource was the land the British had ceded at the Peace of Paris: Native American land.

Acquiring actual title to that land and transforming it into “public land” that could be sold to American settlers to help fill the treasury was vital to the future, even the survival, of the new republic. Having won its independence from the British Empire, the United States turned to build what Jefferson called “an empire of liberty.” In this empire, all citizens shared the benefits.

But who qualified as citizens? Did African Americans? Did women? Did Native Americans?

The Declaration of Independence provided answers and justifications. Hadn’t Native Americans fought against American rights and freedoms at the moment of the nation’s birth? They could not now expect to share those rights and freedoms that had been won at such a cost. The Declaration had also made clear that Indians were “savages,” and Washington, Jefferson, and others believed that the United States had an obligation to “civilize” them. The United States must and would take Native lands; that was inevitable. But it would give them civilization in return, and in their minds, that was honorable.

For Native Americans, this translated into a dual assault on their lands and cultures, which were inextricably linked. In the years following the Revolution, American settlers invaded their homelands. So too, at different times and places, did American soldiers, Indian agents, land speculators, treaty commissioners, and missionaries. Native Americans fought back: they disputed American claims to their homelands, killed trespassers, and sometimes inflicted stunning defeats on American armies.

Not until General Anthony Wayne defeated the allied northwestern tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 did the Indians make peace at the Treaty of Greenville. They ceded most of Ohio to the United States. Then, Indians turned to more subtle forms of resistance in what remained of their homelands, compromising where they had no choice, adapting and adjusting to changes, and preserving what they could of Indian life and culture in a nation that was intent on eradicating both.

The American nation won its war for independence in 1783. Native American wars for independence continued long after.

The Series

-

- Indigenous Peoples of Pulaski County

- The Land, From Ice To European Arrival

- The People, From Ice To European Arrival

- Europeans Arrive

- French Fur Trade & The Beaver Wars

- Indian Wars, Pre-Revolutionary War (The Colonial Wars)

- Revolutionary War

- Indian Wars, Post-Revolutionary War

- United States Takes Shape

- Indiana Takes Shape

- Pulaski County Takes Shape

- Indian Removals, 1700 – 1840

- The Potawatomi, Keepers Of The Fire

- Trail Of Death

- The Chiefs Winamac

- 7 Fires of the Anishinaaabe